Summary

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) issued a short statement on December 24, 2007, on the results of an internal inquiry into its controversial use of cluster munitions during the 34-day war with Hezbollah in July and August 2006.1 During that short conflict, the IDF rained an estimated 4 million submunitions on south Lebanon, the vast majority over the final three days when Israel knew a settlement was imminent. The inquiry was the second internal IDF investigation into the use of the weapon, and like its predecessor it exonerated the armed forces of violating international humanitarian law (IHL). Neither a detailed report nor the evidence supporting conclusions has been made public, however, making it impossible to assess whether the inquiry was carried out with rigor and impartiality, and whether it credibly addressed key issues about targeting and the lasting impact of cluster munition strikes on the civilian population.

Human Rights Watch’s researchers were on the ground in Lebanon throughout the conflict and after, and our findings paint a quite different picture of the IDF’s conduct. Research in more than 40 towns and villages found that the IDF’s use of cluster munitions was both indiscriminate and disproportionate, in violation of IHL, and in some locations possibly a war crime. In dozens of towns and villages, Israel used cluster munitions containing submunitions with known high failure rates. These left behind homes, gardens, fields, and public spaces—including a hospital—littered with hundreds of thousands and possibly up to one million unexploded submunitions.2 By their nature, these dangerous, volatile submunitions cannot distinguish between combatants and non-combatants, foreseeably endangering civilians for months or years to come.

Israel continues to have a duty to investigate publicly, independently, impartially, and rigorously these extensive violations of international humanitarian law. Investigation should include a thorough examination of whether individual commanders bear responsibility for war crimes—that is, for intentionally or recklessly authorizing or conducting attacks that would indiscriminately or disproportionally harm civilians.

The continuing failure of the Government of Israel to mount a credible investigation one and a half years after the end of the 2006 conflict in Lebanon—and failure on the Lebanese side of the border to investigate Hezbollah’s compliance with international humanitarian law—reaffirms the need for the Secretary-General of the United Nations (UN) to establish an International Commission of Inquiry to investigate reports of violations of international humanitarian law, including possible war crimes, committed by both sides during the conflict. The commission should formulate recommendations with a view to holding accountable those on both sides of the conflict who violated the law.3 The findings of this report by Human Rights Watch indicate that Israel’s use of cluster munitions should be part of the commission’s mandate.

Cluster munitions are large, ground-launched or air-dropped weapons that, depending on their type, contain dozens or hundreds of submunitions. During strikes they endanger civilians because they blanket a broad area, and when they are used in or near populated areas, civilian casualties are virtually guaranteed. They also threaten civilians after conflict because they leave high numbers of hazardous submunitions that have failed to explode on impact as designed—known as duds—which can easily be set off by unwitting persons. As yet these weapons are not explicitly banned. However, their use is strictly limited by existing international humanitarian law on indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks. Moreover, global concern at the impact of cluster munitions, all too graphically manifested in south Lebanon, is lending impetus to international efforts to develop a legally binding instrument banning those that have an unacceptable humanitarian effect.

Israel’s strikes in 2006 were the most extensive use of cluster munitions anywhere in the world since the 1991 Gulf War.4 Based on its own field response and a review of public reports, the UN Mine Action Coordination Center South Lebanon (MACC SL) estimated, as of January 15, 2008, that Israel fired cluster munitions containing as many as four million submunitions in 962 separate strikes.5 According to information provided to Human Rights Watch by Israeli soldiers who resupplied Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) units with cluster munitions, the number of submunitions used could be as high as 4.6 million.6 That is more than twice as many submunitions used by Coalition forces in Iraq in 2003 and more than 15 times the number used by the United States in Afghanistan in 2001 and 2002.

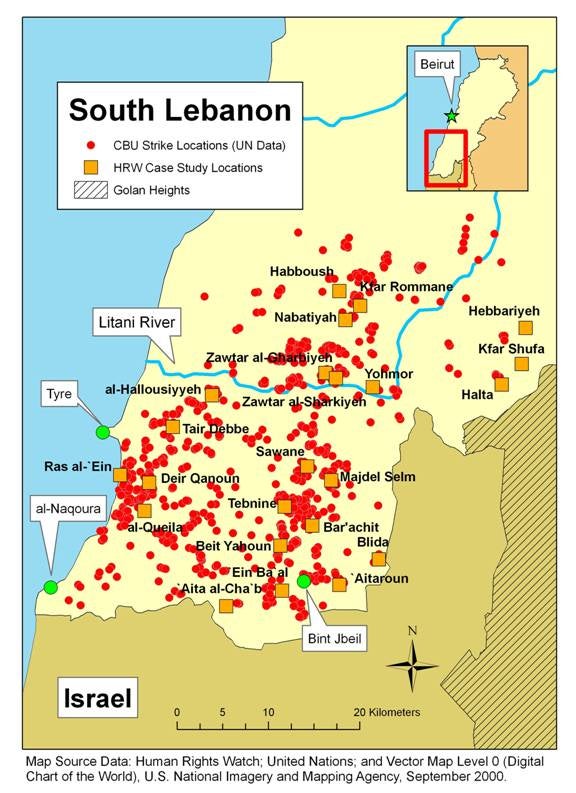

The IDF’s cluster munition strikes were spread over an area of approximately 1,400 square kilometers north and south of the Litani river, an area comparable in size to the US state of Rhode Island (1,214 square kilometers). Within the 1,400 square kilometer area, deminers have so far confirmed an aggregate area of 38.7 square kilometres, including at least 4.3 square kilometers of urban land, 20 square kilometers of agricultural land, and 4 square kilometers of woodland, as directly contaminated by submunitions.7 Looking at the number of submunitions they have cleared compared to the number of strikes, clearance experts have indicated that the failure rates for many of Israel’s submunitions appear to have averaged 25 percent,

leaving behind vast numbers of hazardous unexploded submunitions.8 Based on their personal observations, experts from Human Rights Watch and the UN have judged the level and density of post-conflict contamination in south Lebanon to be far worse than that found in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Kosovo following the use of cluster munitions in those countries. However, it is not just civilians in areas currently known by deminers to be directly contaminated whose lives have been severely affected—people living throughout the 1,400 square kilometer area have had their lives disrupted, as they cannot live in safety until their homes and fields have been inspected and, if necessary, cleared by demining crews.

The cluster munitions fired by Israel into south Lebanon caused serious and ongoing civilian harm. While immediate civilian casualties from the explosions appear to have been limited, the long-term effects in terms of injuries, deaths, and other loss have been considerable. As of January 15, 2008, according to MACC SL, the explosion of duds since the ceasefire had caused at least 192 civilian and 29 deminer casualties.9 The huge number of submunitions used and the high dud rates have severely damaged the economy by turning agricultural land into de facto minefields and interfering with the harvesting of tobacco, citrus, banana, and olive crops.

In the first two weeks of the conflict, Israel launched a relatively small number of cluster munition strikes. Attacks increased in the days after the 48-hour partial suspension of air strikes from July 31 to August 1, 2006; Israeli soldiers serving with an MLRS unit told Human Rights Watch that it was in August that they fired many of their cluster rockets.10

A submunition seriously injured Muhammad Abdullah Mahdi, an 18-year-old mechanic, when he tried to move a car motor at his garage in Zawtar al-Sharkiyeh on October 4, 2006. Shown here about three weeks later, he hemorrhaged, lost half of his left hand, was injured in his right leg, and suffered psychological trauma. © 2006 Bonnie Docherty/Human Rights Watch

The overwhelming use of cluster munitions took place during the final 72 hours of the conflict, when Israel engaged in saturation cluster bombing, hitting more than 850 strike sites with millions of submunitions. According to the United Nations, 90 percent of Israel’s cluster munition strikes took place over this brief period.11 A commander of an IDF MRLS unit told a Ha’aretz reporter, “What we did was insane and monstrous; we covered entire towns in cluster bombs.” He said that, in order to compensate for the cluster rockets’ imprecision, his unit was ordered to “flood” the area with them.12

These strikes occurred after the UN Security Council had adopted Resolution 1701 on August 11 calling for an immediate ceasefire, but before the Lebanese and Israeli cabinets met individually to set the time for the formal ceasefire to take effect on August 14.13 At that time, Israel knew a settlement was likely to be imminent. At this late stage of the war, the majority of civilians had fled the area, but the imminent settlement would clearly lead civilians to return to their homes, many now either directly contaminated by duds or surrounded by contaminated land. It is inconceivable that Israel, which has used cluster weapons on many previous occasions, did not know that that its strikes would have a lasting humanitarian impact.

Israel has repeatedly argued that its use of cluster munitions in south Lebanon was in accordance with “the principles of armed conflict” and was a response to Hezbollah’s deployment and camouflaging of missile launchers “in built-up areas and areas with dense vegetation.”14 According to the IDF, the decision to use cluster munitions “was only made after other options had been examined and found to be less effective in ensuring maximal coverage of the missile launching areas.”15 The Israeli government has told Human Rights Watch that its forces directed all cluster munition fire at legitimate military targets and that for humanitarian reasons “most was directed at open areas, keeping a safe distance from built up areas.”16 When the IDF used cluster munitions in “residential areas/neighborhoods,” it claims it did so “as an immediate defensive response to rocket attacks by Hizbullah from launching sites located within villages.”17 The IDF says “significant measures were taken to warn civilians to leave the area.”18

Human Rights Watch’s researchers visited the sites of cluster munition strikes and talked to local people. They found that cluster munitions affected many villages and their surrounding agricultural fields—locations used intensively by the civilian population.

Human Rights Watch also found that many of the cluster attacks on populated areas do not appear to have had a definite military target. Our researchers, who focused their investigation immediately after the ceasefire on cluster strikes in and around population centers, found only one village with clear evidence of the presence of Hezbollah forces out of the more than 40 towns and villages they visited. While some Israeli cluster attacks appear to have been instances of counter-battery fire, in many of the attacks in populated areas that we examined the few civilians present at the time of the attacks could not identify a specific military target such as Hezbollah fighters, rocket launchers, or munitions.

At this late stage, the final three days of the fighting, the majority of potential eyewitnesses had either fled or were hiding inside buildings or other shelter, making it difficult for them to see activity around them and thus for Human Rights Watch to prove definitively the presence or absence of Hezbollah military targets from interview testimony alone. However, the apparent absence of legitimate military targets in these populated areas matches our broader findings into the conduct of Hezbollah during the war, which revealed that Hezbollah fired the vast majority of its rockets from pre-prepared positions outside villages.19 Furthermore, the staggering number of cluster munitions rained on south Lebanon over the three days immediately before a negotiated ceasefire went into effect puts in doubt the claim by the IDF that its attacks were aimed at specific targets or even strategic locations, as opposed to being efforts to blanket large areas with explosives and duds. Treating separate and distinct military objectives in a single populated area as one target is a violation of international humanitarian law, and if done intentionally, a war crime.

IHL, which governs conduct during armed conflict, requires belligerents to distinguish between combatants and non-combatants and prohibits as “indiscriminate” any attacks that fail to do so.20 Cluster munition attacks on or near population centers, like those launched by Israel, give rise to a presumption that they are indiscriminate, as the weapons are highly imprecise with a large area effect that regularly causes foreseeable and excessive civilian casualties during strikes and afterwards. Furthermore, none of the cluster munition carriers used by Israel was precision-guided. Only a small number of carriers had any type of guidance mechanism. None of the submunitions was guided in any way. These factors support the view that these weapons were used in circumstances in which they were incapable of distinguishing between any actual or potential military objects and the civilians actually or soon to be in the area.

Even in cases where the IDF was attacking a specific military target, its use of cluster munitions violated the principle of proportionality, the legal requirement that the attacker should refrain from launching an attack if the expected civilian harm outweighs the military advantage sought. There is increasing international recognition that when cluster munitions are used in any type of population center, there is a strong, if rebuttable, presumption that the attack is disproportionate, both because of the immediate risk to civilians and the predictable future harm from cluster duds.

In calculating expected civilian harm, Israel needed to consider the presence of civilians. Throughout the war, Israel issued general warnings to civilians in south Lebanon to leave through Arabic flyers and radio broadcasts. Large numbers of civilians fled the area. However, Israel undoubtedly knew that some civilians were unable or unwilling to go because they were poor, elderly, afraid of being killed on the roads, unable to secure transport, or responsible for family property. These civilians thus remained vulnerable to cluster munition attacks. This was the case in the 1993 conflict between Israel and Hezbollah in south Lebanon, and indeed during the course of the 2006 conflict the media was filled with stories on Lebanese civilians dying in Israeli strikes or trapped in place.

In any event, giving warnings does not allow the warring parties then to disregard the continuing presence of some civilians for the purpose of determining whether a planned attack is either indiscriminate or disproportionate. In the latter case, all potential harm to civilians remaining must still be weighed against the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated from an attack, and the attack cancelled if the damage to civilians is disproportionate. Furthermore, given the nature this weapon type and Israel’s overwhelming use of it in the final days of the conflict, the lasting impact of duds must also be a factor in determining whether a planned attack is indiscriminate or disproportionate.

Given the extremely large number of submunitions employed and their known failure rates, harm to remaining and returning civilians was entirely foreseeable. Israel’s use of old weapons and the conditions under which they were fired (often low trajectory or short-range) radically increased the number of duds. Israel was well aware of the continuing harm to Lebanese civilians from the unexploded duds that remained from its prior use of munitions in South Lebanon in 1978 and 1982. Unexploded cluster submunitions from weapons used more than two decades ago—though far less extensively than in 2006—continued to affect Lebanon up to the beginning of the 2006 conflict. Furthermore, testimony from soldiers and the reported IDF prohibition of firing cluster munitions into areas it would subsequently enter indicate that the dangers posed by duds were known to the IDF.

Neither Human Rights Watch’s research nor the limited information offered by the IDF provides affirmative evidence that Israel’s cluster attacks had potential military advantage greater than the significant and ongoing harm that they caused. The paucity of evidence of specific military objectives, the known dangers of cluster munitions, the timing of large scale attacks days before an anticipated ceasefire, and the massive scope of the attacks combine to point to a conclusion that the attacks were of an indiscriminate and disproportionate character. If the attacks were knowingly or recklessly indiscriminate or deliberate, they are war crimes, and Israel has a duty to investigate criminal responsibility on the part of those who authorized the attacks.

Finally, the cluster munitions strike on the Tebnine Hospital on August 13, 2006, appears to have been in violation of the prohibition under international humanitarian law of attacking medical personnel, facilities, and protected persons, including persons hors de combat because of their injuries. We have found no evidence that the hospital was being used for military operations, was housing combatants other than patients (i.e., those rendered hors de combat), or was being used for any other military purpose. These acts, too, must be investigated as violations of the laws of international armed conflict, and as potential war crimes.

Israel’s cluster strikes prompted several investigations after the conflict. The internal inquiry results made public in December 2007 were a follow up to an initial internal IDF “operational inquiry” that had exonerated the Army of violating IHL, but which found that the IDF fired cluster munitions into populated areas against IDF regulations, and that the IDF had not always used cluster munitions in accordance with the orders of then Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Dan Halutz.21 Some IDF commanders vehemently rejected this charge, saying that they acted within their orders.

IDF statements have provided only generalized observations to justify cluster munition attacks, rather than case-by-case information justifying attacks on specific targets. For example, while indicating that there were deviations from orders not to target built up areas, IDF statements do not provide case-by-case information justifying why deviations occurred. Instead, the IDF claims summarily that “IDF forces used the resources in their possession in an effort to curtail the relentless rocket fire at Israeli civilians.” Their statements do not explain the high saturation of towns and villages across south Lebanon. They do not give any reasons why dud rates were so high. The statements do not acknowledge the foreseeable future effects on civilians of high dud rates.22

Two UN inquiries concluded that Israel’s use of cluster munitions contradicted the IHL principles of distinction and proportionality. The US State Department concluded that Israel may have violated classified agreements with the United States regarding when and how US-supplied cluster munitions could be used.23

Human Rights Watch believes that cluster munitions stand out as the weapon category most in need of stronger national and international regulation to protect civilians during armed conflict. Urgent action is necessary to bring under control the immediate danger that cluster munitions pose to civilians during attacks, the long-term danger they pose after conflict, and the potential future dangers of widespread proliferation. Human Rights Watch believes that parties to a conflict should never use unreliable and inaccurate cluster munitions. In 1999 Human Rights Watch was the first nongovernmental organization (NGO) to call for a global moratorium on their use until their humanitarian problems have been resolved. Governments should bear the burden of demonstrating that any cluster munition is accurate and reliable enough not to pose unacceptable risks to civilians during and after strikes.24

International awareness of the need to address cluster munitions is growing rapidly. Most notably, on February 23, 2007, in Oslo, Norway, 46 countries agreed to conclude a treaty banning cluster munitions that cause unacceptable harm to civilians by 2008.25 Another eight states joined the movement in a follow-up meeting in Lima, Peru, in May 2007, and a total of 94 states were on board by the end of the next meeting in Vienna, Austria, in December. The treaty will “prohibit the use, production, transfer and stockpiling of cluster munitions that cause unacceptable harm to civilians” and have provisions for clearance, victim assistance, risk education, and stockpile destruction.26 In 2008, governments will develop and negotiate the treaty at meetings in New Zealand and Ireland.27 “We have given ourselves a strict timeline to conclude our work by 2008. This is ambitious but necessary to respond to the urgency of this humanitarian problem,” said Norway’s Foreign Minister Jonas Ghar Støre.28 This initiative, which closely mirrors the Ottawa process banning antipersonnel mines, follows years of advocacy by Human Rights Watch, the Cluster Munition Coalition, which Human Rights Watch co-chairs, other NGOs, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and states. Lebanon has been a vocal participant in the “Oslo Process,” while Israel has stayed away.

States are also pursuing domestic measures to address cluster munitions. Belgium became the first country to adopt a comprehensive ban on cluster munitions in February 2006, and Austria followed suit in December 2007. Norway declared a moratorium on use in June 2006 and Hungary in May 2007. Parliamentary initiatives to prohibit or restrict cluster munitions are underway in numerous countries. Many countries have in recent years decided to remove from service and/or destroy cluster munitions with high failure rates, and some have called for a prohibition on use in populated areas.

International humanitarian law on the use of cluster munitions is in the process of development, but a consensus is developing that their use in populated areas is a violation, on account of the likelihood of indiscriminate or disproportionate harm to civilians both at the time of the attack and in the future because of unexploded duds. The preamble of the final declaration of the Third Review Conference of the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW), for example, recognizes “…the foreseeable effects of explosive remnants of war on civilian populations as a factor to be considered in applying the international humanitarian law rules on proportionality in attack and precautions in attack.”29 States parties, including Israel and the United States, adopted this language on November 17, 2006. Human Rights Watch believes that the international community should move to establish predictable future effects as not only a violation of IHL but also as a basis for criminal responsibility. The tragedy that has taken place in Lebanon should serve as a catalyst to both national measures and a new international treaty on cluster munitions.

Methodology

This report is based on Human Rights Watch’s on-the-ground research in Lebanon and Israel, supplemented most notably with information provided by MACC SL. It also draws on more than a decade of field research and documentary research on cluster munitions by Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch researchers were in Lebanon throughout the conflict and were the first to confirm Israel’s use of cluster munitions when they documented the IDF’s attack on Blida on July 19, 2006. At the same time, Human Rights Watch researchers working in northern Israel confirmed the widespread presence of cluster munition artillery shells in the arsenals of IDF artillery teams stationed along Israel’s border with Lebanon.

Immediately after the ceasefire, Human Rights Watch researchers traveled to south Lebanon, the location of the most intense cluster munition contamination. They spent six days surveying the extent of the damage from cluster attacks and conducting interviews. Researchers returned to south Lebanon in mid-September 2006 for several days and spent another week in late October 2006 documenting the ongoing aftereffects of the submunitions.

Our researchers investigated more than 50 cluster munition strikes, including strikes in more than 40 towns and villages in south Lebanon. They collected physical evidence of the strikes, took photographs, visited hospitals, and interviewed dozens of civilians who had been directly affected by the cluster munition attacks, including numerous men, women, and children who had been injured by submunitions or submunition duds. Researchers spoke to many Lebanese in their towns and villages just as they were returning home. Human Rights Watch also met with demining professionals from the Lebanese Army, the UN, and NGOs who were cataloguing and clearing the vast fields of deadly submunition duds in Lebanon. Those civilians that had remained in these villages and towns at the time of the attacks, however, were usually taking shelter from bombardment, and so often unaware of whether there were any military targets or military movements in the vicinity.

During the conflict, Human Rights Watch on several occasions made inquiries with Israeli officials regarding use of cluster munitions, especially following the attack on Blida. Human Rights Watch made further inquiries immediately after the conflict, as the scope of use in the final days became clear. Human Rights Watch also called on Israel to provide information about its use of cluster munitions in press releases and public presentations.

In October 2006, Human Rights Watch researchers met with Israeli officials and soldiers in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem to discuss the use of cluster munitions. Most notably, the researchers interviewed four soldiers in MLRS and artillery units that used clusters in July and August. In July 2007, another Human Rights Watch team met with lawyers from the IDF, who provided an overview of the IDF’s position but no specifics about discrete military objectives. In this report, Human Rights Watch has utilized all of the publicly available statements on cluster munitions issued by the Israeli government, as well as statements reported in the media. It also relies on the interview with IDF lawyers and an Israeli document sent in response to Human Rights Watch inquiries, which briefly discusses use of cluster munitions and is annexed to this report.30

Recommendations

To the Government of Israel

Prohibit the use, transfer, and production of unreliable and inaccurate cluster munitions, including all of those types used in Lebanon, and destroy all existing stockpiles. Constitute and empower an independent inquiry to examine all relevant data and investigate impartially and independently the IDF’s use of cluster munitions in Lebanon to assess carefully whether the munitions were used in a manner consistent with international humanitarian law. The investigation should address questions about deliberate use in populated areas, the timing of attacks, the quantity and reliability of cluster munitions used, the specific military objectives for each attack (or lack thereof), whether separate and distinct military objectives were treated as a single one for the purpose of bombardment, and whether there was knowing or reckless disregard for the foreseeable effects on civilians and other protected objects. The results of the investigation should be made public. Hold accountable, including through disciplinary action or prosecution if the facts warrant, those responsible for using cluster munitions in violation of international humanitarian law. Immediately provide to the UN the specific locations of cluster munition attacks, including the specific types and quantities of weapons used, to facilitate clearance and risk-education activities. Provide all possible technical, financial, material, and other assistance to facilitate the marking and clearance of submunition duds and other explosive remnants of war.

To the Secretary-General of the United Nations

Consistent with recommendations made to the UN Secretary-General in the separate reports Civilians under Assault: Hezbollah’s Rocket Attacks on Israel in the 2006 War, published in August 2007, and Why They Died: Civilian Casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 War,published in September 2007:

Use your influence with Israel and Hezbollah to urge them to adopt measures to better comply with international humanitarian law. Establish an International Commission of Inquiry to investigate reports of violations of international humanitarian law, including possible war crimes, in Lebanon and Israel and to formulate recommendations with a view to holding accountable those on both sides of the conflict who violated the law. Include investigation into the use of cluster munitions in the mandate of the inquiry.

To the Government of the United States

Press the Israeli government to mount a credible independent and impartial investigation into the IDF’s use of cluster munitions. Cancel the delivery of 1,300 M26 cluster munition rockets for Multiple Launch Rocket Systems requested by Israel and prohibit any future transfer of unreliable and inaccurate cluster munitions. Make public the findings of its investigation into Israel’s use of cluster munitions in Lebanon, as well as the agreements it has with Israel regarding the use of US-supplied cluster munitions. As the supplier of most of the cluster munitions and other weapons that Israel used in Lebanon, accept special responsibility for assisting with the marking and clearance of submunition duds and other explosive remnants of war. Prohibit the use, transfer, and production of unreliable and inaccurate cluster munitions and begin destruction of existing stockpiles.

To all governments

- Take steps to ban cluster munitions that cause unacceptable humanitarian harm by participating in the international effort initiated by Norway to negotiate a treaty.

- Take national measures to prohibit the use, transfer, and production of unreliable and inaccurate cluster munitions and destroy stockpiles of such cluster munitions.

- Prohibit the use of cluster munitions in or near populated areas.

- Provide support for submunition clearance, risk education, and victim assistance activities in Lebanon.

1 Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Opinion of the Military Advocate General Regarding Use of Cluster Munitions in Second Lebanon War,” December 24, 2007, http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Government/Law/Legal+Issues+and+Rulings/Opinion+of+the-Military+Advocate+General+regarding+use+of+cluster+munitions+in+Second+Lebanon+War+24.htm (accessed December 29, 2007).

2 Email communication from Dalya Farran, media and post clearance officer, MACC SL, to Human Rights Watch, January 15, 2008.

3 Human Rights Watch has separately reported on violations of international humanitarian law by Israel in the wider bombing campaign in Lebanon in 2006 and violations of international humanitarian law, including incidents involving cluster munitions, by Hezbollah. The scale of Israel’s use of cluster munitions in south Lebanon dwarfed that of Hezbollah. See Human Rights Watch, Why They Died: Civilian Casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 War, vol. 19, no. 5(E), September 2007, http://hrw.org/reports/2007/lebanon0907/, and Human Rights Watch, Civilians under Assault: Hezbollah’s Rocket Attacks on Israel in the 2006 War, vol. 19, no. 3(E), August 2007, http://hrw.org/reports/2007/iopt0807/.

4 Between January 17 and February 28, 1991, the United States and its coalition allies used a total of 61,000 cluster munitions, releasing 20 million submunitions in Iraq, a country more than 40 times bigger than Lebanon. Human Rights Watch, Fatally Flawed: Cluster Bombs and Their Use by the United States in Afghanistan, vol. 14, no. 79(G), December 2002, http://hrw.org/reports/2002/us-afghanistan/, p. 40.

5 Email communication from Dalya Farran, media and post clearance officer, MACC SL, to Human Rights Watch, January 15, 2008.

6 Human Rights Watch interviews with IDF reservists (names withheld), Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, Israel, October 2006. Unless otherwise noted, all interviews cited in this report were done in Lebanon.

7 Email communication from Dalya Farran, media and post clearance officer, MACC SL, to Human Rights Watch, January 15, 2008. For a breakdown of land by type, as of November 2006, see United Nations Development Program (UNDP), “CBU Contamination by Land Use,” current as of November 29, 2006.

8 MACC SL, “South Lebanon Cluster Bomb Info Sheet as at November 4, 2006,” http://www.maccsl.org/reports/Leb%20UXO%20Fact%20Sheet%204%20November,%202006.pdf (accessed March 18, 2007); email communication from Dalya Farran, media and post clearance officer, MACC SL, to Human Rights Watch, September 12, 2007.

9 Email communication from Dalya Farran, media and post clearance officer, MACC SL, to Human Rights Watch, January 15, 2008 (including attachment of cluster munition casualty data) [hereinafter MACC SL Casualty List]. The Landmines Resource Center (LMRC) also keeps track of cluster munition casualties and counted 239 civilian and 33 deminer casualties as of January 2, 2008. Email communication from Habbouba Aoun, coordinator, Landmines Resource Center, to Human Rigths Watch, January 2, 2008 (including attachment of cluster munition casualty data) [hereinafter LMRC Casualty List].

10 Human Rights Watch interviews with IDF reservists (names withheld), Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, Israel, October 2006.

11 UN officials citing this statistic include the UN’s then emergency relief coordinator and under-secretary-general for humanitarian affairs, Jan Egeland; the UN’s humanitarian coordinator in Lebanon, David Shearer; and the program manager of the UN Mine Action Coordination Center South Lebanon, Chris Clark. See, for example, UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), “Lebanon: Cluster Bomb Fact Sheet,” September 19, 2006; “UN Denounces Israel Cluster Bombs,” BBC News, August 30, 2006. Ninety percent of the war’s total of 962 strike sites is about 866 strike sites from the last three days. Note that each site may include multiple strikes. Email communication from Dalya Farran, media and post clearance officer, MACC SL, to Human Rights Watch, January 15, 2008.

12 Meron Rapoport, “When Rockets and Phosphorous Cluster,” Ha’aretz, September 30, 2006, http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/761910.html (accessed July 24, 2007).

13 The 19-point resolution called for, among other provisions, “a full cessation of hostilities based upon, in particular, the immediate cessation by Hizbollah of all attacks and the immediate cessation by Israel of all offensive military operations.” United Nations Security Council, Resolution 1701 (2006), S/RES/1701 (2006), http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N06/465/03/PDF/N0646503.pdf?OpenElement (accessed May 13, 2007), para. 1. See also “Security Council Calls for End to Hostilities between Hizbollah, Israel, Unanimously Adopting Resolution 1701 (2006),” United Nations press release, August 11, 2006, http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2006/sc8808.doc.htm (accessed July 26, 2007).

14 Israel’s Response to Accusations of Targeting Civilian Sites in Lebanon During the “Second Lebanon War,” document contained in email communication from Gil Haskel, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, to Human Rights Watch, May 8, 2007, in response to a Human Rights Watch letter to Defense Minister Amir Peretz sent January 8, 2007.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Opinion of the Military Advocate General Regarding Use of Cluster Munitions in Second Lebanon War.”

18 Ibid.

19 For fuller analyses of Hezbollah’s violations of international humanitarian law during the conflict, see Human Rights Watch, Civilians under Assault, and Human Rights Watch, Why They Died. Our research shows that on some occasions, Hezbollah fired rockets from within populated areas, allowing its combatants to mix with the Lebanese civilian population, or stored weapons in populated civilian areas in ways that violated international humanitarian law. Such violations, however, were not widespread. We found strong evidence that Hezbollah stored most of its rockets in bunkers and weapons storage facilities located in uninhabited fields and valleys, that in the vast majority of cases Hezbollah left populated civilian areas as soon as the fighting started, and that Hezbollah fired the vast majority of its rockets from pre-prepared positions outside villages.

20 Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I) of 8 June 1977, 1125 U.N.T.S. 3, entered into force December 7, 1978, arts. 48, 51(4)(a, b).

21 Greg Myre, “Israeli General Orders Lebanon Inquiry,” New York Times, November 20, 2006; UNOCHA, “Israel: Army to Investigate Use of Cluster Bombs on Civilian Areas,” IRINnews.org, November 22, 2006. The Israeli government statement on the probe refers to the earlier “operational inquiry into the use of cluster munitions during the conflict, when questions were raised regarding the full implementation of the orders of the General Staff concerning the use of cluster munitions.” Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “IDF to Probe Use of Cluster Munitions in Lebanon War,” November 21, 2006, http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Government/Communiques/2006/IDF%20to%20probe%20use%20of%20cluster%20munitions%20in%20Lebanon%20War%2021-Nov-2006 (accessed September 3, 2007). Israel has not made public either the regulations or the orders.

22 Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “IDF to Probe Use of Cluster Munitions in Lebanon War”; Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Opinion of the Military Advocate General Regarding Use of Cluster Munitions in Second Lebanon War.”

23 David Cloud, “Inquiry Opened Into Israeli Use of US Bombs,” New York Times, August 25, 2006.

24 Some states are developing and procuring cluster munitions that may not present the same dangers to civilians as most existing cluster munitions because they are capable of more accurate targeting and are more reliable. For example, some sensor fuzed weapons contain a small number of submunitions, each with an infrared guidance system directing the submunition to an armored vehicle.

25 Oslo Conference on Cluster Munitions, “Declaration,” February 22-23, 2007, http://www.regjeringen.no/upload/UD/Vedlegg/Oslo%20Declaration%20(final)%2023%20February%202007.pdf (accessed March 2, 2007).

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 “Cluster Munitions to Be Banned by 2008,” Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs press release, February 23, 2007, http://www.regjeringen.no/en/ministries/ud/Press-Contacts/News/2007/Cluster-munitions-to-be-banned-by-2008.html?id=454942 (accessed March 2, 2007).

29 Third Review Conference of the High Contracting Parties to the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW), “Final Document, Part II, Final Declaration,” CCW/CONF.III/11 (Part II), Geneva, November 7-17, 2006, p. 4 [hereinafter CCW Third Review Conference, “Final Declaration”].

30 The document sent by the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs to Human Rights Watch on May 8, 2007, is a verbatim excerpt from a ministry document posted on its website on April 1, 2007, entitled “Preserving Humanitarian Principles While Combating Terrorism: Israel’s Struggle with Hizbullah in the Lebanon War,” http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Terrorism-+Obstacle+to+Peace/Terrorism+from+Lebanon-+Hizbullah/Preserving+Humanitarian+Principles+While+Combating+Terrorism+-+April+2007.htm (accessed August 14, 2007). The document is not a direct response to the information requested by Human Rights Watch. To date, we have not received any further information from the Israeli authorities responding directly to our request for information.