III. Background

Abuses Since the 2002 Ceasefire

The ceasefire agreement between the Sri Lankan government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE)8 in effect since February 2002 brought a welcome if ultimately temporary end to major military operations. It did not, however, curtail serious human rights abuses, and in some ways it facilitated them by permitting LTTE operatives greater leeway to conduct intelligence operations and assassinations in government-controlled areas. Human Rights Watch and others reported on more than 200 extrajudicial killings during the period, the vast majority of which were attributed to the LTTE. 9 Pro-government Tamil political parties, whose members were frequently targets of LTTE attacks, were also implicated in killings. The government made no discernable effort to investigate any of these killings or hold those responsible to account.

On August 12, 2005, alleged LTTE gunmen assassinated Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar at his Colombo home. In the months that followed, LTTE forces increasingly targeted Sri Lankan army units with ambushes and landmine attacks. Killings attributed to persons connected to pro-government Tamil armed groups, most notably the murder of pro-LTTE Tamil National Alliance parliamentarian Joseph Pararajasingham while he attended Christmas Eve mass in Batticaloa town in December 2005. The LTTE is believed responsible for the murder of Kethesh Loganathan, deputy head of the government’s Peace Secretariat, in Colombo in August 2006.

The Sri Lankan military forces and the police’s Special Task Force, which conducts counterinsurgency operations, were implicated in a number of killings of Tamil civilians in 2006. Among those were the extrajudicial killing on January 2, 2006, of five Tamil students in Trincomalee town; the “disappearance” of eight young men from a Hindu temple in Jaffna in May; the extrajudicial killing of five Tamil fishermen on Mannar Island in June; the execution-style slaying of 17 staffers with Action Against Hunger, an international aid organization, in August; and the September 17 murder of ten Muslim laborers south of Pottuvil.

Karuna’s Break from the LTTE

The political landscape in Sri Lanka’s north and east was permanently altered by the departure of the LTTE’s eastern forces in March 2004. Vinayagamoorthy Muralitharan, commonly known as Colonel Karuna and the LTTE’s senior military commander in the Batticaloa area, split from the LTTE with the several-thousand-member LTTE force under his command. Although the reasons for his actions are unclear, Karuna stated at the time that he did so because Tamils from the east had fared badly under the LTTE’s predominantly northern leadership. Others have suggested that Karuna decided to break away because of a rivalry with the head of the LTTE’s intelligence wing for the number two position in the LTTE.10

In April 2004 LTTE forces launched an overwhelming assault against Karuna’s fighters. Karuna quickly disbanded his forces, and escaped with a small group of his supporters. In a dramatic gesture that won him favor with the local population, he encouraged some 2,000 child soldiers to return to their families (see Chapter VII). As an LTTE commander, Karuna had been notorious for recruiting and at times abducting children for use in Tiger forces. To this day, Karuna’s whereabouts are unknown.

Karuna’s faction gradually reasserted influence in both government and previously LTTE-controlled areas in the east. The very existence of the Karuna group complicated the 2002 ceasefire agreement. After the breakaway, Karuna asked to be formally included under the ceasefire agreement, which would have obligated his forces to abide by the terms of the ceasefire but given him a seat at further peace talks. The LTTE rejected this and instead demanded that the Karuna group be disarmed under the ceasefire agreement as a “Tamil paramilitary group.”11 Karuna rejected this on the grounds that this provision did not apply to his forces, which had been part of the LTTE under the peace accord. Small-scale fighting and escalating tit-for-tat killings between the LTTE and Karuna group persisted into 2006.

In 2004 Karuna organized a political party, the Tamil Makkal Viduthalai Pulikal (Tamil Peoples Liberation Tigers or TMVP), which throughout 2006 established party offices in Colombo and in towns in the country’s eastern districts. As president of the party, Karuna has expressed a willingness to contest future elections.

The defection of the Karuna faction was a significant blow for the LTTE. It not only cost it several thousand cadres, but deprived it of control or influence in significant parts of the east, as well as a major source of new recruits. The perceived weakness of the LTTE might have encouraged the Sri Lankan military leadership to believe that major renewed hostilities against the LTTE could lead to significant territorial gains, if not outright victory.

Escalation of Fighting Since mid-2006

In July 2006 small-scale fighting between the LTTE and government forces became major military operations. Citing the LTTE’s closure of a reservoir sluice gate near Trincomalee town, the Sri Lankan armed forces undertook a major military offensive—the first since the 2002 ceasefire agreement—that continued after the sluice gate opened again.

In late July the LTTE countered first with an attack on Mutur town in Trincomalee district, which had largely been emptied of government troops redeployed to support the military’s offensive. The LTTE then conducted a major yet unsuccessful attack on the Jaffna peninsula in mid-August, briefly cutting off the peninsula from the rest of the country. The short-term humanitarian crisis created by the Jaffna attack became a long-term crisis, as neither the LTTE nor the government in the ensuing months took sufficient steps to ensure that sufficient food, fuel, and medical assistance reached the nearly half-million population of the peninsula. The LTTE threatened to attack Jaffna-bound cargo ships, while the government made only half-hearted efforts to reopen the main roadway, which goes through LTTE-controlled territory.

Several major military operations have taken place since September. The Sri Lankan armed forces captured the strategically important town of Sampur, across the bay from Trincomalee. In a separate attack the armed forces suffered several hundred casualties attacking dug-in LTTE positions on the eastern end of the Jaffna peninsula.

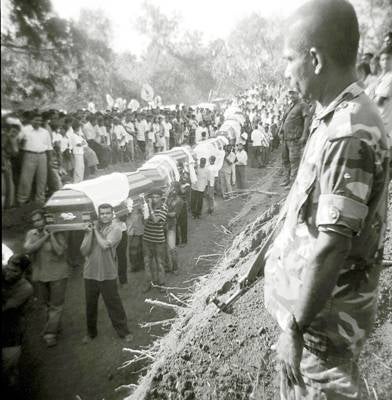

A mass grave for the victims of the LTTE’s June 15, 2006

landmine attack on a civilian bus, that killed 67 people.

© 2006 Q. Sakamaki/Redux

Throughout the fighting, neither side has shown much concern for the well-being of the civilian population. In June the LTTE targeted a civilian bus with a landmine, killing 64 civilians, including many children. In August the Sri Lankan air force bombed a building in rebel territory that killed as many as 51 young women and girls receiving civil defense training from the LTTE. The LTTE is believed responsible for a pair of public bus bombings south of Colombo on January 5-6, 2007, which killed 21 passengers and injured 120.

In the last months of 2006 much of the fighting consisted of long-range artillery duels between the two forces in the Vaharai area of Batticaloa district, in the vicinity of Karuna’s forces. Civilians bore the brunt of the casualties. LTTE forces fired heavy weapons from populated areas, including near displaced persons camps, placing civilians at risk. The army often responded with or initiated indiscriminate shelling. On November 8 this dynamic resulted in the deaths of more than 40 displaced civilians and injuries to nearly 100 others who had sought refuge outside a school. Fearful of continued shelling, more than 20,000 people fled LTTE-territory by walking for days through jungle or risking their lives on overcrowded boats. Many families now are living in uncertain circumstances in areas accessible to the Karuna group.

At this writing, fighting continues in Vaharai, and tens of thousands more civilians have been displaced. Whether and where new major military operations will occur in 2007 is unclear, but the possibility of such fighting may pressure both the LTTE and the Karuna group to add to their ranks—including by unlawfully recruiting or abducting children to serve in their forces.12

8 The Agreement on a Ceasefire between the Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (CFA), signed on February 21, 2002, had the stated objective to “find a negotiated solution to the ongoing ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka.” The agreement set up modalities of the ceasefire, measures to restore normalcy, and the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission. The agreement is available at http://www.slmm.lk/documents/cfa.htm (accessed January 1, 2007).

9 See, for example, Human Rights Watch, “Sri Lanka: End Killings and Abductions of Tamil Civilians,” May 24, 2005, available at http://hrw.org/english/docs/2005/05/24/slanka10996.htm (accessed January 1, 2007); Commission on Human Rights, Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, Philip Alston, “Mission to Sri Lanka (28 November to 6 December 2005),” E/CN.4/2006/53/Add.5, March 27, 2006.

10 International Crisis Group, “Sri Lanka: The Failure of the Peace Process,” Crisis Group Asia Report No. 124, November 28, 2006, p. 9.

11 CFA, sec. 1.8.

12 On January 2, 2007 Sri Lankan Army Commander Sarath Fonseka said the government would stay on the attack, taking Vaharai within the month. “After eradicating the Tigers from the East, full strength would be used to rescue the North,” the army commander said. (PK Balachandran, “Lankan Army Hopes to Clear East by March,” Hindustan Times (New Delhi), January 3, 2007, http://www.hindustantimes.com/news/181_1887249,001302310000.htm (accessed January 9, 2007) and “Jaffna Next, Army Chief Tells Mahanayakes,” Daily Mirror (Colombo), January 3, 2007, http://www.dailymirror.lk/2007/01/03/front/5.asp (accessed January 9, 2007).