<<previous | index | next>>

Additional Ethiopian Military Abuses against Anuak Civilians

The incidents described above are only a small piece of the pattern of rights violations committed by the Ethiopian army against the Anuak population in Gambella. Human Rights Watch examined numerous other cases of abuses since the December 2003 massacre. These include further and continuing raids on Anuak neighborhoods and villages that have left a trail of death, rape, looting and destruction. ENDF forces have also committed widespread human rights abuses against individual Anuak civilians throughout Gambella. These typically occur when soldiers pass through Anuak communities in rural areas or encounter Anuaks in the countryside. In many areas, most notably around Gok and Jor in Gilo wereda, abuses are ongoing and frequent.

Extrajudicial Killings

Human Rights Watch documented 104 extrajudicial killings of Anuak civilians by ENDF forces in December 2003 and throughout 2004, not including the more than 400 victims of the December 2003 massacre.91 Many of those killings occurred during attacks on Anuak villages, while others followed encounters between groups of soldiers and Anuak men in the countryside.

As documented below, ENDF forces have attacked Anuak neighborhoods in some of the region’s largest towns and have also raided several villages in Okuna, Abodo and Powatalam kebeles between February and September 2004. In these attacks, soldiers killed dozens of Anuak residents, many of whom were shot while trying to flee.

Extrajudicial Killings Committed During Attacks on Anuak Civilian Populations

On the last day of January or at the beginning of February 2004, ENDF soldiers and highlander civilians carried out an attack against the Anuak population in Dimma, a town in the extreme south of Gambella. This violence was in apparent reprisal for a bloody attack on a highlander community of artisanal miners carried out by armed Anuak outside of Dimma on January 30, 2004, described below. The violence began at around 11 a.m., when soldiers and highlander civilians stoned to death a student named Ochalla Chan in Dimma.92 Throughout the afternoon, mobs chased scores of Anuak civilians from their homes and attacked them in the streets. ENDF soldiers shot and killed several unarmed Anuaks while others were set upon with machetes and clubs by highlander civilians.93 One thirty-five-year-old civil servant stepped outside of his home to see what was happening when he heard the first gunshots and watched a group of soldiers shoot and kill a man and a woman in the street near his home.94 Another man told Human Rights Watch that he barricaded himself inside his house along with his wife and infant son when the violence began and some time later he heard screams and gunfire very close by. When he ventured outside several hours later, he saw the bodies of one of his neighbors, a mechanic named Omot, and a woman he did not recognize splayed across the ground near Omot’s home. Both bodies had bullet wounds and had been badly mutilated.95

In February or March96 2004, several dozen soldiers attacked and looted a village called Abodo in the Jor region of Gilo wereda. At least seven people were killed, most of them as they fled in the direction of the nearby river. One young man described how the attacking soldiers killed one of his neighbors:

They came with trucks and when they saw the village they dropped out of them and came on foot. We only saw them when they were near to the village. As soon as we saw them we all started running—we all knew about Gambella town. They didn’t ask any questions but started shooting. We ran into the bush, crossed the river and started running again….I saw them kill one man. He is not normal—he has a physical problem. When we started running he could not run fast and could not get far from the village. They shot him and stood on top of him. He didn’t die immediately. His relatives were trying to carry him after the soldiers shot him but then they left him and ran away.97

The soldiers occupied the village for several days after the attack.

Early one morning in late February or early March,98 ENDF soldiers descended upon Anuak neighborhoods in Abobo, a town that lies forty kilometers to the south of the regional capital, burning homes and firing indiscriminately at panicked Anuak civilians. At least fifteen Anuak residents lost their lives, most of them cut down by gunfire as they tried to escape.99 One fifty-year-old woman described how she fell behind the younger and stronger members of her family as they all fled in the initial moments of the attack. “We saw three groups of soldiers coming through the bush chasing us,” she said. “There were many guns from that side and this side. The soldiers were shouting, ‘Kill them!’” One man who was running several paces ahead of her was shot and killed just before she escaped into a dense tangle of trees. “He was a bit ahead of me when he was shot and after he fell I passed his body,” she said. “I heard the gun and then he just fell.”100 Another woman was running towards the shelter of a stand of nearby trees when the woman running next to her was shot and killed by a soldier some distance behind them. She continued running and hid herself in the hollow trunk of a dead tree, only to find that her hiding place was home to a colony of bees. A group of some fifteen soldiers appeared nearby before she could extricate herself, so she was forced to remain still and silent until they passed while the insects stung her all over her body.101

ENDF forces have carried out similar attacks in Anuak villages scattered throughout Gambella. In an attack that completely destroyed the Anuak village of Okuna Pino near Abobo in March or April of 2004, soldiers killed at least fourteen Anuak civilians.102 One blind woman named Agwa Nugat could not escape and was burned alive inside her home when soldiers set fire to the village.103 In Powatalam kebele, ENDF troops attacked the villages of Poljai, Jaru and Tirol in August and September 2004 and killed at least two Anuak civilians. When ENDF soldiers arrived in Tirol, they shot a man they encountered on the outskirts of the village. His young wife, who watched him die, was at a loss to explain the killing. She said simply, “They met and they shot him. No words were exchanged. When I saw him fall, I ran away to the forest.”104 When they entered the village, soldiers accused its inhabitants of sheltering Anuak shifta before setting fire to their homes and attacking some of the fleeing villagers.105

Other Extrajudicial Killings

Ethiopian soldiers have also killed Anuak civilians in isolated incidents that did not involve attacks on larger towns or villages. Many Anuak farmers work fields located some distance from the villages they live in, and Human Rights Watch received several reports of military patrols killing farmers on their way to or from their fields. Late one afternoon in October 2004, a young man named Ojulu Ochala was killed as he walked home from his fields near Okuna Pino. An ENDF patrol had surrounded the village as they prepared to move into and search it; startled by Ojulu’s approach from the other direction, one or more soldiers opened fire on him when he stepped into view. One witness to the killing said:

We were following him, walking together from the farm to the village. We were together at first but then he pulled ahead of us. It was late in the afternoon and we ran into the military by accident. They just shot him without asking any questions….After he was shot he fell down and then we ran….They ordered the old men to throw him away without burying him. So they did this, they threw him in the bush somewhat far from the village…but then after the soldiers left they buried him.106

Many Anuak villagers told Human Rights Watch that ENDF personnel generally offered no explanations for such killings to relatives and affected communities. One farmer from Tirol village in Powatalam kebele said that a passing patrol shot and killed a man from the village named Owat Ogala in January 2004. The soldiers came to notify the villagers that they had killed the man but did not explain why they had done it, saying only, “there is someone there. Go and bury him.”107

The military routinely conducts patrols through remote stretches of uninhabited forest near Anuak villages. The objective of these patrols is purportedly to ensure security in rural areas and root out armed Anuak shifta whomsoldiersbelieve to be hiding in isolated villages and in the bush.108 Often, however, ENDF forces appear to make no effort to distinguish male Anuak civilians from the shifta they claim to be hunting. Unarmed young men have frequently been shot at and in many cases killed while traveling between villages, and many ENDF patrols seem to view any Anuak civilian who runs away from them as a legitimate target. Many Anuak men from rural villages told Human Rights Watch that they make a habit of fleeing whenever they see or hear soldiers approaching along secondary roads or trails; two said that they had been shot at by soldiers who spotted them from a distance as they tried to run into the grass.109 Human Rights Watch spoke with one man who narrowly escaped being shot while walking to Pinyudo from a village in Jor in October 2004. “Of course,” he said, “on these roads when you see the military you have to run if you see them first. So I ran and they started shooting at me but they couldn’t hit me and I ran into the bush.”110

Rape

Encouraged by a climate of near-total impunity, ENDF personnel have raped Anuak women in and around villages throughout Gambella. Some of these rapes have been committed in the course of broader attacks on Anuak civilian populations, but most have not. The majority of the rapes reported to Human Rights Watch occurred when women were attacked by military personnel when they were outside of their villages. Anuak communities near ENDF garrisons experience the most frequent abuses.

The deep and lasting stigma associated with rape in Anuak society drives many Anuak rape survivors to conceal attacks even from their families. For the same reason, while most of the Anuak villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Gambella said that ENDF soldiers had raped women from their communities in 2004, some of them were not willing to discuss specific cases in any detail. This was true of men as well as women; one man from a village near Gok Dipatch explained his refusal to discuss a number of rapes that had reportedly taken place in his village by saying that, “even your wife, they can come and take her and you cannot tell it to another person. If you tell another person you are spoiling the name of your wife.”111 As a result, Human Rights Watch was only able to obtain testimony about some of the rapes that have occurred since December 2003 in surveyed communities.

Human Rights Watch has documented many rapes of Anuak women committed by ENDF soldiers along isolated roads in Gambella. One woman told Human Rights Watch that a group of twelve ENDF soldiers gang raped her on a road between Gok Jinjor and Gok Dipatch in Gilo wereda sometime in the first few months of 2004. She said:

I was on my way to a nearby village and…I was caught by soldiers. They beat me and raped me at that time. There were twelve soldiers and all twelve of them raped me. They kept me for three hours. [After this] I became very exhausted and I was bleeding. From Gok Jinjor to Gok Dipatch usually takes two hours, but after I faced this problem, it took six hours. I received no treatment. I reported to my relatives, not to outsiders, because when they see a woman bleeding they may think she has made an abortion. When I was caught by the troops, my child ran away. I reached Gok Jinjor without knowing where my child was. After I arrived, I received information that the child joined another group of people and I sent my relatives from group to group.… I have suffered long term harm. It is still difficult for me to walk. The same thing has happened to other women.112

Other rapes have occurred in similar circumstances. In May 2004, a young woman was raped by four soldiers beside a road near Chentoa in Gilo wereda while her teenage sister screamed in protest.113 Another woman was raped alongside of a road near Abobo in November 2004. Although she suffered serious pain and bleeding for two weeks after the attack, she never sought medical treatment.114 Human Rights Watch also received reports of numerous rapes committed by ENDF soldiers along roads throughout Gilo wereda, especially in Gok and Jor.115

Ethiopian troops have also raped women in and around their own villages. Seven women from Okuna Pino have reportedly been raped by soldiers coming through the village on patrol since August 2004; one young man told Human Rights Watch that his cousin was gang raped at gunpoint by four soldiers there in November 2004. “One soldier aimed his gun at her,” he said, “and as he did so he told her to give herself over to another one.”116 In August or September 2004, a group of soldiers, reportedly from the garrison in Illea, pulled a woman and her husband from their home near Itang, gang raped her just outside the house, and then shot and killed her husband.117 In a village in Powatalam kebele, ENDF personnel reportedly raped a woman inside of her own home one night in October 2004.118

Soldiers stationed in permanent ENDF garrisons in Gok Dipatch, Illea and Pochalla have reportedly raped women from nearby Anuak villages with such frequency that most local women no longer walk outside of their villages alone. One man from a village near the Illea garrison told Human Rights Watch that his community had given up trying to report incidents of rape to the garrison’s commanding officers. Instead, “the women are told not to go to far places, and if they go to collect firewood to go in a big group and to run if they see soldiers.”119 Human Rights Watch received reports of five rapes that took place near the garrison in Illea in 2004.120

Beatings and Torture

ENDF soldiers routinely detain and interrogate Anuak men they encounter in searches of Anuak villages or in the countryside. According to people who have witnessed or been subjected to them, these interrogations are generally linked to efforts to locate Anuak shifta or search for illegal firearms.121 In many cases, soldiers beat their detainees during interrogation and these beatings are often severe enough to rise to the level of torture.122 In other cases, ENDF personnel have beaten Anuak men without questioning them at all.

Many villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that whenever ENDF patrols approach their villages, the men from the village run into the bush and hide until the soldiers leave. The soldiers leading the patrols usually tell villagers that they are looking for people connected to the shifta or for illegal guns, and interrogate any young or middle-aged men they find. One man from a village near Pinyudo called Butaboro explained, “When they circle the village they are looking for a man above fourteen years old. For smaller children it is not serious— only if you are over fourteen it is very serious if they get you.”123

Witnesses and victims told Human Rights Watch that soldiers routinely beat the men they find in these sweeps of Anuak villages. Two men from Okuna Pino said that throughout 2004, ENDF patrols that passed through their village every one to two weeks beat and interrogated any young men they found there.124 “The troops do not like to see young men,” one of them said. “When they see one, they capture him, beat him, and ask him many questions.” A relative of this man suffered several broken ribs when he was beaten by ENDF soldiers in mid-2004 and had to seek medical treatment at the Catholic mission’s clinic in Abobo.125 In September 2004, a man named Ochut Lai was taken into custody by a group of soldiers in Pinyudo as he left a local beer house. He later said that he was taken to the ENDF garrison and severely beaten with iron bars as he was interrogated for information about illegal guns and Anuak shifta. He never recovered from his injuries and died two months later.126

ENDF soldiers often accuse any men they believe to be from outside of the village they are searching of engaging in unlawful activities. One young man who was beaten when soldiers arrived in his village in September or October 2004 recalled:

I was caught one time in my village….They had circled it to look for young men like us….They separated the men into young and old. They said to us, “Where are you from? You don’t look like people from here.” We said, “No, we are from this village. It is you who are new to this place.” They had no response to this, they just said, “No, we don’t know you. We only know these old men, not you.” Then they started beating us with their guns.127

One man from a village called Otiel in the Jor region of Gilo wereda told Human Rights Watch that for a period of several months in 2004, any men found on the roads near his village were routinely accused of being shifta, detained, interrogated and severely beaten by soldiers stationed in a temporary encampment nearby. Whenever someone was detained, the village headman would be called to the camp the next morning and asked whether he recognized the detainee as someone from the village. If the man was from Otiel, he would be released and sent home to nurse his wounds. If the village headman did not recognize him, he would be kept in custody. No one in Otiel had been able to find out what happened to the several men who were not released.128

ENDF patrols that encounter Anuak men on secondary roads or in the bush often detain, interrogate and beat them. One twenty-year-old man from Okuna Pino described what happened to him when he encountered a group of soldiers along a secondary road in June 2004:

I was carrying some clothes in a plastic bag and accidentally met some soldiers. I didn’t have a chance to run. They asked me what I was carrying. I was bending down to open the bag and when I was facing down [one soldier] kicked me in the face with his boot. After he kicked me, I was a bit stunned and then I opened the bag and showed him that it was just clothes and a Bible. Then another man came and hit me in the ribs with the end of his gun. I fell down. They asked me, “What do you do?” and I said that I am a student. They told me to show them my ID and I told them that there are no IDs for students in the villages. They said that I am a liar. By this time I was very much affected [badly hurt] and so they didn’t think of beating me again because I seemed as though I could not get up. I just lay there for maybe two hours….I was hurt badly. Sometimes I still feel pain in my ribs.129

Human Rights Watch heard credible reports of dozens of similar incidents. This form of abuse is so widespread that many Anuak villagers described it as a routine part of their existence that one simply has to accept. Several of the Anuak men interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they considered a severe beating to be the inevitable outcome of any encounter with ENDF soldiers. Despite the frequency and severity of these abuses, people often said that they did not think such incidents were worth discussing. As one farmer from a village in Jor called Omedho said, “The beatings are always happening—this is not a major problem. We don’t bother to take their names. If all they do is beat you, you are lucky.”130

Witnesses and victims from every Anuak community mentioned in this report gave credible accounts of abuses that fit within the pattern set forth above. Continuing abuses of this nature are especially frequent and widespread in the Gok and Jor regions of Gilo wereda.131

Destruction of Property and Looting

Between December 2003 and May 2004, ENDF forces raided, looted and razed Anuak neighborhoods in Gambella town, Pinyudo, Abobo and Dimma as well as several villages in Tedo, Okuna, Abodoand Powatalam kebeles. In the course of those attacks, soldiers have destroyed Anuak houses and grain stores, slaughtered or stolen livestock and looted homes, schools and clinics.

In March or April 2004,132 ENDF soldiers attacked the village of Okuna Pino near Abobo, destroying nearly every house in the village along with anything else that could be smashed or burned. One witness to the attack described the devastation wrought by the attackers:

They burned all of the village and the school and the clinic. This was in [March or April]. I was there but we escaped….When they came they shot a gun and we all ran and scattered in the forest. We could see everything from the forest because it is not dense and you can see the village very clearly. They were taking fire and putting it on the houses. They also went to the grain stores and burned them. Also [there are] some big pots where we keep maize for famine times. They took sticks and hit the pots and after the maize was scattered they took grass and put it on the maize and burnt it….There are fires at the homes—these are cooking fires. They took grass from the roofs and lit it in these fires and then they used the burning grass to light other houses….There was nothing left. My house was burned down.133

Other attacks have been equally destructive. As discussed above, ENDF soldiers razed over 1000 houses in the attack on Anuak neighborhoods in Pinyudo town on December 17, 2003. The attack on Anuak populations in Dimma in January 2004 left over 200 houses destroyed, and ENDF soldiers destroyed over 400 Anuak homes in Abobo in early2004.134 Most of the houses in three villages in Tedo kebele were destroyed in three separate military attacks beginning in March 2004.135 More recently, soldiers burned several houses in each of three Anuak villages in Powatalam kebele in September 2004.136

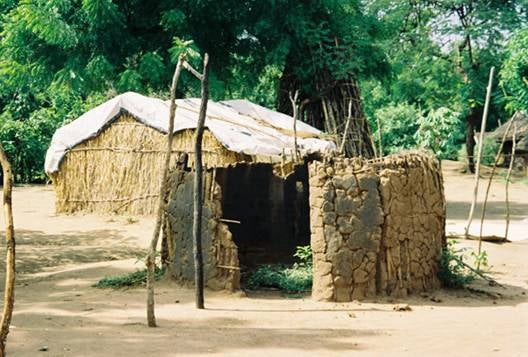

A typical Anuak tukul in Abobo.

© 2004 Human Rights Watch

The tukul in

the foreground was destroyed by ENDF soldiers during the attack on Anuak

neighborhoods in Pinyudo.

The house in the background was built after the

attack, with plastic sheeting used as makeshift roofing material.

© 2004 Human

Rights Watch

ENDF forces have destroyed other property in the course of these attacks as well. In the attacks on Anuak communities in Pinyudo and Abobo described above, soldiers destroyed grinding mills that were operated cooperatively by neighborhood residents. At the time of Human Rights Watch’s mission to Gambella, those mills were still nonfunctional and the residents who depended on them were forced to pay high prices to use mills operated by local merchants.

Farmers in many villages store surplus powdered maize in large clay pots as insurance against lean times. Witnesses to several attacks on rural Anuak communities described how soldiers went from house to house smashing these pots before spoiling their contents by burning them. In some cases the soldiers explained their actions by claiming that they needed to search for bullets buried in the powdered maize.137

Even villages that have not suffered attacks by ENDF forces have often seen their inhabitants’ most important property looted by nearby garrisons or patrols. Theft of livestock is especially common, especially in the western part of Gilo wereda where many rural Anuak maintain large herds of cattle, sheep and goats.138 One man from Ulaw kebele in Jorsaid:

The people of Jor have lots of cattle. [The soldiers] come and take as much as they want—they are always eating meat. Some they eat and some they sell to highlanders in [Pinyudo] town. Even sometimes when people of Jor come [to Pinyudo] they recognize their cattle.139

Livestock theft has been a continuing problem in Tedo kebele.140 Several villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that soldiers often offer them absurdly low prices for their cattle and say that if they do not accept the offered prices their cattle will be taken without compensation. Another villager from Jor lamented, “If you do not accept the price they give you then you will lose the money and your cattle as well.”141

ENDF soldiers have also looted clinics and schools in some Anuak villages. At least one school and clinic were looted during the attack in Pinyudo in December 2003.142 Soldiers who established an encampment near Otiel for three months in 2004 ransacked the village’s clinic and school, destroying much of the property within and using the tables from both buildings as beds.143 In February or March, soldiers who attacked the village of Abodo in the Jor region of Gilo wereda smashed all of the furniture in the school and used some of the wood to cook themselves dinner after the attack.144 A school in Chentoa in Gilo wereda was reportedly looted by soldiers who used a truck to carry off the furniture inside.145

Displacement and Food Shortages

The continuing violence in Gambella has forced several thousand people from their homes, leaving the already-troubled region saddled with thousands of new internally displaced persons (IDPs) and driving thousands more to seek refuge in neighboring countries. The prevailing climate of insecurity generated by ENDF abuses has also led many Anuak farmers to abandon their fields, exacerbating Gambella’s already serious food security problems.

Violence against rural Anuak communities has driven thousands of Anuak civilians from their homes since December 2003. An estimated eight to ten thousand people fled more than two hundred kilometers on foot across the Sudanese border to seek refuge in the town of Pochalla in southern Sudan in the early months of 2004.146 The flow of refugees across the border has reportedly slowed to a trickle in more recent months and several thousand refugees returned to Gambella in mid- to late-2004, but thousands still remain. Aid workers providing assistance to the local community estimate that the Anuak refugee population in and around Pochalla now remains static at around 6500 people.147 In addition, some 1200 Anuak refugees have made their way to Kenya.148

The repeated outbreaks of ethnic violence and widespread abuses committed by ENDF forces have left an enormous proportion of Gambella’s population internally displaced. In July 2004, the Norwegian Refugee Council estimated that 51,000 people in Gambella had been displaced by conflict at some point since 2003; that figure represents at least twenty percent of the region’s total population.149 A large proportion of Gambella’s Anuak IDPs have migrated to large towns and villages such as Pinyudo, Abobo and Gambella town. Many people, however, have tried to escape the violence afflicting their communities by spending days or even weeks at a time living in the bush hiding from ENDF patrols. A farmer from a village called Tier Kudhi in Perbongo kebele said that he along with many of his neighbors had fled their village and lived in the forest for several weeks starting in July 2004. “Now many people are in the forest,” he said. “You go group by group to a place where there is water and you can at least hunt some food.”150 One man from Gok Dipatch told Human Rights Watch that many people from his village were often forced to seek refuge in the bush and subsisted by “eating fruits like the monkeys in the forest.”151 Human Rights Watch met one man who had fled a patrol he saw approaching his village in Gok Dipatch. The patrol had remained in the area for several days and after spending three or four nights in the forest waiting for the soldiers to leave, he gave up and made his way on foot to Pinyudo. He spoke with Human Rights Watch a few hours after arriving in the town. He had not eaten in days, his clothes were in tatters and his skin was covered in bites and scratches. “I was in the forest for almost a week,” he said, “and I have only the clothes on my back.”152

Gambella is also facing serious food shortages in 2005. Agricultural production in the region is expected to fall by 50 percent in 2005 as compared with 2004, and nearly 50,000 people (including 27,000 Anuak), are expected to require food aid in 2005.153 These problems are not due solely to ethnic conflict and displacement; sporadic and insufficient rains ruined some farmers’ crops in 2004. However, OCHA and Ethiopia’s Disaster Prevention and Preparedness Commission (DPPC) cite conflict and insecurity as the main reason that the total area under cultivation in Gambella decreased by 25 percent from 2003 to 2004.154 Human Rights Watch interviewed several farmers who said that they had abandoned their fields in 2004 because of the danger from shifta-hunting ENDF patrols. Others said that they traveled to their fields only sporadically, when there were no ENDF soldiers in the area, and that they had lost some of their unguarded crops to monkeys, cattle and other animals.155

[91] Since this figure is drawn from interviews with Anuak civilians from a relatively small number of villages, it is likely that the total number of such killings in Gambella during this period has been substantially higher. Human Rights Watch received secondhand reports of killings in and around many other communities throughout Gambella in 2004 but was not able to document them. Many people interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they had heard of many people being killed by ENDF soldiers in remote areas of Gilo wereda.

[92] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #80, Gambella, late 2004.

[93] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #13, 22, 23, 24, 80 and 81, Gambella and Ruiru, Kenya, late 2004.

[94] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #24, Ruiru, Kenya, late 2004.

[95] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #23, Ruiru, Kenya, late 2004.

[96] This attack occurred during the month of Yekatit according to the Ethiopian calendar (a variety of the Julian calendar). In 2004, Yekatit overlapped with both February and March in the Gregorian calendar.

[97] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #56, Gambella, late 2004.

[98] Witnesses reported that the attack took place in the month of Yekatit according to the Ethiopian calendar. In 2004, Yekatit overlapped with both February and March in the Gregorian calendar.

[99] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #20, 29, 37, 40, 64, 65 and 69, Gambella and Ruiru, Kenya, late 2004.

[100] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #40, Gambella, late 2004.

[101] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #69, Gambella, late 2004.

[102] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #31, 39 and 68, Gambella, late 2004. The attack occurred in the month of Megabit according to the Ethiopian calendar.

[103] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #68, Gambella, late 2004.

[104] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #77, Gambella, late 2004.

[105] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #77 and 82, Gambella, late 2004.

[106] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #39, Gambella, late 2004.

[107] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #82, Gambella, late 2004.

[108] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #31, 42, 46, 57 and others, Gambella, late 2004; Human Rights Watch interview with federal government official, Addis Ababa, late 2004.

[109] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #35 and 49, Gambella, late 2004.

[110] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #49, Gambella, late 2004.

[111] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #53, Gambella, late 2004.

[112] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #84, Gambella, late 2004.

[113] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #56, Gambella, late 2004.

[114] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #70, Gambella, late 2004.

[115] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses # 31, 42, 49, 53, 55, 56, 76, 78 and 79, Gambella, late 2004.

[116] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #39, Gambella, late 2004.

[117] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #62, Gambella, late 2004.

[118] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #82, Gambella, late 2004.

[119] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #62, Gambella, late 2004.

[120] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #5, 60 and 62, Gambella and Ruiru, Kenya, late 2004.

[121] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #26, 33, 46, 70, 76 and 77, Gambella, late 2004.

[122] Article 1 of the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment defines torture as “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.”

[123] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #33, Gambella, late 2004.

[124] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #39 and 68, Gambella, late 2004.

[125] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #68, Gambella, late 2004.

[126] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #73, Gambella, late 2004.

[127] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #56, Gambella, late 2004.

[128] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #46, Gambella, late 2004.

[129] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #39, Gambella, late 2004.

[130] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #49, Gambella, late 2004.

[131] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #42, 49, 53, 55, 58, 76, 78 and 79, Gambella, late 2004.

[132] This attack took place in the month of Megabit according to the Ethiopian calendar.

[133] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #41, Gambella, late 2004.

[134] Human Rights Watch interviews with regional officials, Addis Ababa and Gambella, late 2004.

[135] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #32, 35 and 71, Gambella, late 2004.

[136] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #65, 66, 77 and 82, Gambella, late 2004.

[137] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #39, 68, 70, 76, 80 and 83, Gambella, late 2004.

[138] Human Rights Watch interviews with witnesses #42, 44, 46, 49, 55, 56 and 78, Gambella, late 2004.

[139] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #55, Gambella, late 2004.

[140] See supra Case Studies.

[141] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #46, Gambella, late 2004.

[142] See supra Case Studies.

[143] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #28, Gambella, late 2004.

[144] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #56, Gambella, late 2004.

[145] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #49, Gambella, late 2004.

[146] Email from international aid organization official, January 15, 2005.

[147] Ibid.

[148] Human Rights Watch interviews with Anuak community leaders, Ruiru, Kenya, late 2004.

[149] Norwegian Refugee Council, Global IDP Database, Ethiopia Country Profile, [online] http://www.db.idpproject.org/Sites/idpSurvey.nsf/wCountries/Ethiopia (retrieved January 26, 2005).

[150] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #38, Gambella, late 2004.

[151] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #78, Gambella, late 2004.

[152] Human Rights Watch interview with witness #34, Gambella, late 2004.

[153] Disaster Prevention and Preparedness Commission, “2005 Food Supply Prospect,” December 23, 2004, [online] http://www.ocha-eth.org/Reports/downloadable/FoodSupplyfinaldec2005.pdf (retrieved January 26, 2005).

[154] Ibid. See also OCHA, 2005 Humanitarian Appeal for Ethiopia, December 23, 2004, [online] http://www.uneue.org/Reports/downloadable/FocusonEthiopiaDecember2004.pdf (retrieved January 26, 2005); Human Rights Watch interviews with regional officials, Gambella, late 2004.

[155] Human Rights Watch interviews with witness #72, 79 and 82, Gambella, late 2004.

| <<previous | index | next>> | March 2005 |