<<previous | index | next>>

V. Human Rights Abuses in the Mongbwalu Gold Mining Area

During eighteen months of conflict in 2002 and 2003, Hema and Lendu armed groups fought to control the gold-mining town of Mongbwalu in Ituri. As they passed control of the rich prize back and forth five times, they also slaughtered some two thousand civilians, often on an ethnic basis. In addition, they carried out summary executions, raped and otherwise injured thousands of civilians, engaged in torture, and arbitrarily detained persons whom they saw as enemies. During the frequent clashes, tens of thousands of civilians were forced to flee their homes, losing much or all of their goods to looting or destruction.

The town of Mongbwalu lies some 150 km south of Durba within the Ituri section of the gold mining concession controlled by the state gold company OKIMO. Gold was first discovered in the area by Australian prospectors in 1905 and has been mined ever since. The Mongbwalu area is presumed to be one of the richest goldfields in the OKIMO concession and is home to the large industrial mine of Adidi, the former Belgian mines of Makala and Sincere, and a substantial gold refining factory where gold ingots were produced until 1999. At its height of operations in the 1960s and 1970s the OKIMO gold mining operation employed some six thousand workers and was the main provider of employment in northeastern Congo. Although it was in the center of the territory belonging to the Nyali ethnic group, people of different ethnicities had come to live in Mongbwalu to work in the gold mines or in related activities. Lendu formed the majority of its fifty thousand inhabitants with Hema a far smaller number. Despite ethnic clashes elsewhere in Ituri, Mongbwalu stayed generally calm before 2002 under the control of RCD-ML troops supported by soldiers of the Ugandan army; gold operations continued on a much reduced scale, most of it for the benefit of the RCD-ML and Ugandan soldiers.

In April 2002 the situation changed when the RCD-ML, strengthened by new solidarity with the national government in the Sun City Agreement, came into conflict with the Hema. Under the leadership of Thomas Lubanga, the Hema began to form structured militia groups, who would later be formally known as the UPC. The RCD-ML responded by attacking Hema civilians in Mongbwalu with the help of Lendu combatants. Hema militia then targeted Lendu civilians in the town and outlying areas. For greater security people who had lived in ethnically mixed areas moved to areas inhabited by others of their own group. As one woman said, “People of each group fled to their own areas. Tensions were very high.”49

By early August 2002 the Ugandan government had decided to withdraw their support from RCD-ML – in part because of its links with Kinshasa – and to back its local challenger, the UPC. Ugandan troops and Hema combatants dislodged RCD-ML forces from Bunia, the capital of Ituri. Shortly thereafter the Ugandans reduced their backing for the Hema, suspecting they were moving towards an alliance with Rwanda and Rwanda increased its support for the UPC. According to a confidential supplement prepared by the U.N. panel of experts, Rwanda trained more than one hundred UPC combatants in the Gabiro training center in Rwanda between September and December 2002 and trained other intelligence officers directly in Bunia.50 Meanwhile, the RCD-ML, humiliated by its loss of Ugandan backing and its hasty retreat from Bunia, forged even closer links to the Lendu militia, providing them with arms and carrying out joint attacks to stop or reverse UPC advances.

Once in control of Bunia, the UPC claimed to have set up a government for Ituri and moved to capture towns both north and south of Bunia. According to witnesses and documentary evidence, the UPC began planning an attack on Mongbwalu in September 2002, intent on winning control of its gold.51 Even before a shot was fired, UPC President Lubanga asked the then general director of OKIMO, Etienne Kiza Ingani, who was himself Hema, to prepare a memo on how mining operations could be managed under UPC control. In the document Mr. Kiza warmly congratulated the UPC on its anticipated victory – weeks before Mongbwalu had actually been captured – and suggested the establishment of a “mixed Executive Council [including the UPC and OKIMO] to take stock of the terrain … and decide quickly what we need to do.”52 In meetings about investment in the mines held in Mongbwalu after the UPC victory, the finance director of OKIMO, Roger Dzaringa Buma, also a Hema, was presented as the financial advisor to UPC President Lubanga, illustrating a continuing close relationship between OKIMO officials and the UPC armed group.53

The UPC failed in its first attempt to take Mongbwalu on November 8, 2002, its forces pushed back by RCD-ML combatants and Lendu militia. Before undertaking a second attempt, UPC officials won the support of Commander Jérôme Kakwavu Bukande, who had commanded the RCD-ML 5th Operational Zone in the gold mining region of Durba. But in September Commander Jérôme had been driven from Durba by a combined force of two other rebel movements, the RCD-N and the Congolese Liberation Movement (MLC). He had retreated to Aru, a post at the Ugandan frontier that offered lucrative tax revenue. According to another senior combatant who also left the RCD-ML for the UPC at the same time, Commander Jérôme expected to get gold and ivory in return for his participation, as well as arms. He said,

Lubanga gave him [Commander Jérôme] the materials – mortars, rocket-propelled grenade launchers, grenade launchers that could be mounted on a vehicle, and many bombs. All of this was sent by plane via Air Mbau [Mbau Pax Airlines] an Antonov leased by the UPC. Some other ammunition came via road from Bunia. [Commander] Manu escorted it to Mongbwalu. This was the reserve.54

Rwandan support was also crucial to the UPC in its efforts to take Mongbwalu. In addition to providing military training, as mentioned above, the Rwandans supplied the UPC—and their ally Commander Jérôme—with weapons. The same combatant associated with Commander Jérôme said,

The weapons we received from Lubanga were from Rwanda. They had Rwanda written on the boxes. There is also a difference in the type of weapons that Rwanda and Uganda use. The MAG was a different model, an MMG while the Ugandans use a G2. Also the mortars were a different size from Rwandan ones.55

A later confidential supplement from the U.N. panel of experts confirmed that mortars, machine guns, and ammunition were sent from Rwanda to the UPC in Mongbwalu between November 2002 and January 2003. On other occasions arms sent from Kigali were airdropped at the UPC stronghold of Mandro.56

Thomas Lubanga, President of the UPC. © 2003 Khanh Renaud

According to the combatant who also participated in the assault on Mongbwalu, the operation was organized and led by UPC leader Lubanga, Commanders Bosco Taganda (UPC Chief of Operations) and Commander Kisembo Bahemuka (UPC Chief of Staff) as well as Commander Jérôme Kakwavu and two other officers associated with him, Commanders Salumu Mulenda and Sey. Rwandans reportedly assisted in planning and directing the attack, to the displeasure of Commander Jérôme and some of his men. As the combatant said, “It was the Rwandans who organized the attack- they gave the orders. The people of Jérôme were not happy with this.” In assessing the role of Rwanda in Ituri, the U.N. panel of experts told the U.N. Security Council that key UPC commanders reported directly to the Rwandan army high command including Rwandan army Chief of Staff, General James Kabarebe, and Chief of Intelligence, General Jack Nziza.

Massacres and other Abuses by the UPC and their Allies

Massacre at Mongbwalu, November 2002

The UPC strengthened by Commander Jérôme’s combatants after the failed attack of November 8, 2002 attacked the Mongbwalu area again on November 18, 2002. During the six-day military operation, UPC forces slaughtered civilians on an ethnic basis, chasing down those who fled to the forest, and catching and killing others at roadblocks. In a co-ordinated strategy UPC and Commander Jérôme’s forces attacked to the north of Mongbwalu in the villages of Pili Pili and Pluto drawing the more experienced RCD-ML soldiers out of the town. Others, led by Commander Bosco, attacked to the south at the airport. A witness said the attackers worked systematically, going from one house to the next. He recounted,

The UPC arrived in Pluto at about 9:00 a.m.. . . If they caught someone they would ask them their tribe. If they were not their enemies they would let them go. They killed the ones who were Lendu. . . . The UPC would shout so everyone could hear, “We are going to exterminate you – the government won’t help you now.”57

Another witness described what he saw in Mongbwalu,

The Hema [UPC] and … [Commander Jérôme’s forces] came into town and started killing people. We hid in our house. I opened the window and saw what happened from there. A group of more than ten with spears, guns and machetes killed two men in Cité Suni, in the center of Mongbwalu. . . . They took Kasore, a Lendu man in his thirties, from his family and attacked him with knives and hammers. They killed him and his son (aged about 20) with knives. They cut his son’s throat and tore open his chest. They cut the tendons on his heels, smashed his head and took out his intestines. The father was slaughtered and burnt. We fled to Saio. On the way, we saw other bodies. 58

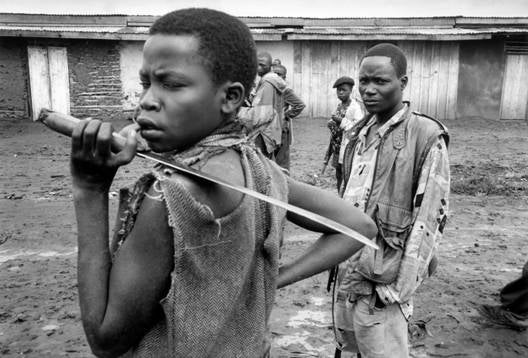

A Lendu FNI fighter

carries a rocket-propelled grenade. Proceeds from the sale of gold are

frequently used to purchase weapons and other supplies for armed groups in

Ituri. © 2003 Karel

Prinsloop/AP

Many civilians fled with the Lendu combatants to Saio, about seven kilometers away, only to be attacked there the next morning. Civilians ran into the forests while others tried to hide in Saio, including at a church called “Mungu Samaki.” When UPC combatants found civilians, they slaughtered them.59 A witness said,

The [UPC] were using incendiary grenades and burned houses that still had people in them, like Mateso Chalo’s house. Ngabu was a Lendu who couldn’t flee. He had lots of children and was trying to carry them. They shot at him. He fell on one of his children and died. Another woman, Adjisu was shot in the leg. She had her baby with her. They caught her as she was trying to crawl along the ground. They cut her up with machetes and killed her. They cut the baby up as well. Some people were thrown into the latrines. The UPC said they were now the chiefs.60

The UPC pursued the fleeing Lendu combatants, the RCD-ML forces and thousands of civilians as they took to the forest. In a ten day trek seeking safety at Beni and elsewhere, scores of civilians died, particularly children and the weak. Those who tried to flee by road were caught at roadblocks and many of them were killed. One witness who fled said he had seen UPC combatants kill 120 people at a roadblock at Yedi. He later covered the bodies with leaves.61

Some civilians who were not Lendu returned to Mongbwalu in the following days. According to them, UPC Commander Bosco was in charge at first but then was replaced by Commander Salongo as the sector commander of Mongbwalu. Those who returned reported that Lendu, Nande and Jajambo peoples were not welcome in Mongbwalu. As one witness recounted, “You couldn’t be Lendu in Mongbwalu or you would be eliminated.”62 Witness reported numerous bodies in the streets and fresh graves around the UPC military headquarters at the “apartments”, formerly the lodgings of OKIMO employees. Those returning more than one week after the attack reported corpses still lying on the streets.63

Massacre at Kilo, December 2002

In December 2002 and early 2003, UPC forces attacked Kilo, Kobu, Lipri, Bambu and Mbijo, all villages near Mongbwalu. They took Kilo on December 6 and a few days later Commander Kisembo and Commander Salumu ordered the deliberate killing of scores of civilians. They held a meeting in the center of town with some sixty Nyali local authorities. According to witnesses at the meeting, Commander Kisembo said that all Lendu would be expelled from the area and that those who refused to go would be killed.64 UPC combatants arrested men, women and children with bracelets, assuming them to be Lendu.65 They forced them to dig their own graves before massacring them. UPC combatants also forced Nyali residents to help cover the graves.

A Hema UPC combatant patrolling a village in Ituri. Machetes

are frequently used by the FNI and UPC during their attacks. © 2003 Marcus

Bleasdale

One man who was not Lendu said,

I saw many people tied up ready to be executed. The UPC said they were going to kill them all. They made the Lendu dig their own graves. I was not Lendu but forced to dig as well or I would be killed. The graves were near the military camp. It started in the morning. They called people to quickly dig a hole about four feet deep. They would kill the people by hitting them on the head with a sledgehammer. People were screaming and crying. Then we were asked to fill the grave up. We worked till about 16:00. We buried the victims still tied up. There must have been about four [UPC] soldiers doing the killing. They would shout [at the victims] that they were their enemies. One of the officers present was Commander David [Mpigwa]. Commander Kisembo was also there and he saw all this. He was giving the orders along with David. I don’t know how many they killed in total, but I must have seen about one hundred people killed.66

According to a special U.N. report on events in Ituri, UPC Commander Salumu led further military operations that killed at least 350 civilians from January to March 2003.67

Based on witness statements, information from local human rights organizations and other sources, Human Rights Watch estimates that of the total two thousand civilians killed at and near Mongbwalu during the period November 2002 to June 2003, at least eight hundred – including the 350 cited by the U.N. report – were killed in the attacks led by the UPC in late 2002 and early 2003.68 Over 140,000 people were displaced by the series of attacks, some of whom remain in camps or in the forest at the time of writing. “I want to go back to my job in Mongbwalu,” said one witness, “but not when there are still lots of guns there that are used to kill people.”69

Arbitrary arrest, torture and summary executions

After taking control of Mongbwalu, Hema combatants arbitrarily arrested and, in some cases, summarily executed civilians suspected of being Lendu or of having helped Lendu.70 One man, detained on the accusation that his brothers had helped the Lendu, was beaten for two days and then confined in a bathroom with four others at the “apartments,” headquarters of the UPC. He said that two of the four, elderly Lendu men, were killed and that the other two, who were not Lendu, also were taken away on the tenth day, just before his release.71 Another witness related having been arbitrarily imprisoned at a military camp. He said he saw combatants select out and kill prisoners on an ethnic basis.72

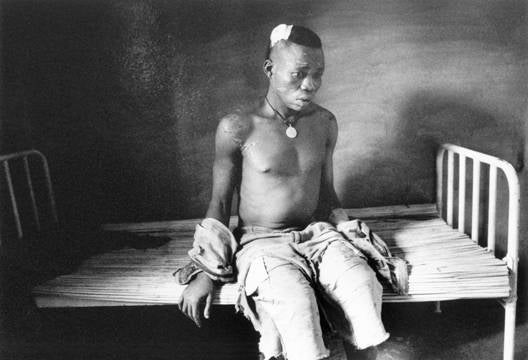

A Lendu man held in detention by the UPC, July 2003. The UPC frequently

carried out campaigns searching for Lendu after taking control of an area.

Known locally as “the man-hunt”, individuals detained during such campaigns are

often subjected to tortured and then executed. © 2003 Marcus Bleasdale

One of the best known cases of arrest and execution involved Abbé Boniface Bwanalonga, the elderly Ngiti priest of Mongbwalu parish, who was arrested with three nuns and two other men on November 25, 2002.Targeted because of his ethnicity, Abbé Bwanalonga was the first priest killed as part of the Ituri conflict.73

In December, church officials confronted UPC President Lubanga about the responsibility of UPC combatants for the killing of Abbé Bwanalonga. According to them, Lubanga expressed his regret for the death and supposedly promised an investigation, which was never carried out.74 Some Hema community leaders in Dego village, not far from Mongbwalu, reportedly sought to identify the perpetrators in order to avert possible repercussions on their community, but the results, if any of this effort, are not known.

Abbé Boniface Bwanalonga, the Ngiti (Lendu) priest arrested, tortured

and killed by UPC militias during their attack on Mongbwalu in November 2003.

Abbé Bwanalonga was about 70 years old at the time of death and had been unable

to flee to safety. He was killed for belonging to the Ngiti (Lendu) ethnic

group. © Private.

Mining the Gold: Instances of Forced Labour

According to one witness, the UPC promised gold to men who joined their forces in the attack on Mongbwalu.75 Ordinary combatants may not have been the only ones who expected to share in the wealth. One journal that specializes in mining affairs reported that Rwandans had struck a deal with the UPC and that Lubanga promised to ship gold from the area under its control out through Kigali rather than through Kampala.76 In January 2003 Mr. Kiza, general director of OKIMO, and Mr. Dzaringa, its finance director, hosted potential investors who had come from Rwanda to discuss industrial mining at Mongbwalu. The Rwandan visitors toured the gold mines, the factory and the laboratory before meeting the two OKIMO officials together with UPC military and political leaders.77 OKIMO employees had been asked to prepare estimates on costs of resuming operations and they showed this data and geological maps to the investors. According to one, the rest of the negotiations were handled by the UPC. 78

While waiting for the capital needed to begin industrial operations, the UPC encouraged workers, who had fled, to return and begin artisanal mining.79 UPC commanders sought to identify and recruit OKIMO employees to help with the work.80 According to miners and local authorities, some miners resumed working in the three main mines in Mongbwalu and at open pit areas known locally as Bienvenue and Monde Rouge; they had to pay a portion of their ore each day to UPC combatants who guarded the mines.81

But the UPC apparently found the number of such miners insufficient and they began forcing others to work one of three shifts a day, morning, afternoon, or night, in the mines. A miner said,

The workers were not paid. It was hard labor. They had to dig under big stones without machines. They had only hand tools like pick-axes. They were given bananas and beans to eat and they were beaten. Some tried to run away by pretending to go to the toilet. The Hema militia guarded them. As the Lendu had fled, all the other groups were made to dig.82

Another person forced to work five times recounted his first experience:

I had been there for less than a week when three soldiers came to find me at my house. They took me to a part of town called Cite Shuni. There I was given a basket of rocks to pound down into dust so they could get the gold. I had never done this before and I was forced to do it all day long. There were about 20 of us in that place forced to do the same work. I got so many blisters on my hands that I couldn’t go on. The work was very hard. It seemed each soldier had his own workers producing for him. I did everything I could to escape from there.83

UPC combatants themselves also mined gold, sometimes with assistance from local miners whom they had required to work with them and who were sometimes paid a small percentage of the findings.84 One former OKIMO employee forced to help the UPC set up a mining brigade said the group included fifty to one hundred combatants with a small number of skilled miners. This brigade mined in surrounding areas of Mongbwalu including Mbijo, Baru, Yedi and Iseyi under UPC military command.85

Increased Commerce

According to witnesses, the number of flights in and out of Mongbwalu increased sharply as gold production began under UPC control. According to witnesses, gold went out and arms came in. One witness said:

When the UPC were in Mongbwalu they sent their gold to Bunia and from there it was sent to Rwanda. In exchange they got weapons. A number of soldiers told me this. When they were here there were at least two flights per day. The gold was used to buy weapons and uniforms.86

Another witness said he was forced to dig a hole for storage of weapons at the UPC headquarters in Mongbwalu. He said,

They put weapons into this hole. The weapons were still new. Some of the guns had wheels that needed to be pushed. They said they didn’t know how to use these but that the Rwandans did know and they would come to show them how. My soldier friends told me that the weapons had been bought with gold. The hole was well guarded by them.87

As previously mentioned, a confidential supplement by the U.N. panel of experts stated that weapons were delivered from Rwanda to Mongbwalu between November 2002 and January 2003.88 Information from community leaders and other military sources also confirms the delivery of arms although it does not establish that gold was traded for them.89

Justice for UPC crimes

Human Rights Watch reported on the November 2002 massacre at Mongbwalu in July 2003 and a year later a report to the U.N. Security Council also detailed the massacre of civilians around Mongbwalu. To date the perpetrators of these crimes have not been brought to justice either by the UPC or by the DRC transitional government.

The UPC splintered into two factions in early December 2003. The branch led by Commander Kisembo changed from a largely military movement to a political party and received recognition as a national political party in mid-2004. Commander Kisembo was arrested by MONUC troops on June 25, 2004 for continued military recruitment but was later released without charge. Since October 2003 Thomas Lubanga, leader of the other UPC faction, has been restricted by the transitional government to Kinshasa where he lives at the Grand Hotel. He was arrested in Kinshasa in March 2005 but has not yet been charged with any crimes. Commander Bosco remains the chief military officer in charge of the UPC Lubanga faction based in Ituri. MONUC claims he is responsible for the attack on a MONUC convoy resulting in the death of a Kenyan peacekeeper in January 2004 and for taking a Moroccan peacekeeper hostage in September 2004.90

Commanders Salumu and Sey, still part of Commander Jérôme’s forces, were selected for training at the Superior Military College in Kinshasa in preparation for joining the newly integrated Congolese army as senior officers. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any vetting carried out by DRC military officials or international donors who support army integration to determine their unsuitability for senior posts because of their involvement in human rights abuses.91

In March 2003, the UPC lost control of the Mongbwalu area and the profits from its gold mines when they were attacked and pushed back by a new alliance of forces led by their former ally turned enemy: the Ugandan army.

Massacres and other Abuses by the FNI, FAPC and the Ugandan Army

After having dropped the Hema, Ugandan soldiers built a new alliance with the Lendu, who had created the FNI party under Floribert Njabu in November 2002. At the end of February 2003, Commander Jérôme also ended his link with the UPC and created his militia, known as the FAPC, based in the important border town of Aru, northeast of Mongbwalu. According to a special report to the U.N. Security Council on Ituri, the FAPC was created with direct Ugandan support.92

With international pressure growing to withdraw their troops from Ituri, Ugandan soldiers sought to secure maximum territory for their local allies. On March 6, 2003 reportedly in response to an attack by the UPC, the Ugandan army drove the UPC out of Bunia with the assistance of Lendu militias. One former Lendu leader who participated in the operation said that he and his men had done so at the request of Ugandan army Brigadier Kale Kayihura.93 Ugandan soldiers and FNI combatants chased fleeing UPC troops northwards towards Mongbwalu.

Massacre at Kilo, March 2003

On March 10, 2003 the Ugandan and Lendu forces attacked Kilo, a town just south of Mongbwalu, with the Lendu arriving several hours before the Ugandans.94 The Lendu combatants met little resistance from the UPC and began killing civilians who they presumed to be of Nyali ethnicity, accusing them of having helped the Hema. According to local sources, they killed at least one hundred, many of them women and children. They looted local residences and shops and required civilians to transport the booty for them.95 Residents walking on the road near the town of Kilo nearly a month later still reported the smell of corpses rotting in the forest.96

A local woman witnessed her house being burned and then saw the Lendu combatants kill a man, five women, and a child with machetes. She was then forced to help transport loot for the Lendu combatants. She recounted that, en route, the Lendu selected four children between ten and fifteen years old, Rosine, Diere, Kumu and Flory, from the group and killed them and then killed five more adults. When some of the women faltered under the heavy loads they were forced to carry, the Lendu killed them and cut off their breasts and then cut their genitals. The witness said,

At Kilo Mission on top of the hill there were many Lendu combatants. They had a few guns but mostly machetes, bows and arrows. They were very dirty and had mud on their faces so we wouldn’t recognize them. On the hill we saw many bodies of people who had been killed. They were all lying face down on the ground. They were naked. The Lendu were getting ready to burn the bodies. There were many of them, too many to count.97

According to witnesses, Commander Kaboss commanded the attack. He reported to Commander Matesso Ninga, known as Kung Fu, who was in charge of operations for the FNI, though he was not seen at Kilo during the massacre. At the time, the FNI Military Chief of Staff was Maitre Kiza.98

Ugandan troops under Commander Obote arrived a few hours after the Lendu and tried to stop their killing. The witness said,

When the Ugandan soldiers arrived they started to hit the Lendu and shot at them. They said to them, “Why have you killed people, we said you could loot but not to kill people. You will tarnish our reputation.” They tried to return some of the loot but the Lendu were starting to run away. The Ugandans said they regretted the way the Congolese behaved and they regretted very much that the chief’s house had been burned and ruined.99

Although the Ugandans stopped the killings in the town, the FNI combatants continued to kill people in the surrounding villages such as Kabakaba, Buwenge, Alimasi and Bovi. “If the Ugandans heard about the killings,” said one witness, “they would go to try and stop it, but it was often too late.100 Local authorities also reported the rape of some twenty-seven women and the burning of villages, including Emanematu and Livogo which were completely destroyed.101

Although the Ugandan soldiers tried to limit FNI abuses after the Kilo attack, they neither disarmed the combatants nor ended their military alliance with them. Instead they continued their joint military operation towards Mongbwalu arriving there on March 13, 2003 and set up the military headquarters for the 83rd Battalion.102 The next day a community leader sought security assurances from Ugandan Commander Okelo, who was in charge of the military camp. According to him, Commander Okelo confirmed that “he controlled the Lendu combatants and he had given them one week to put down their traditional weapons.”103 Witnessed observed Ugandan army troops carrying out joint patrols with Lendu combatants and reported that “it was clear the Ugandan army was in command.”104

When the Ugandan soldiers left Ituri two months later, they were still working closely with the FNI. According to an Ugandan army document dated May 1, 2003, Ugandan Major Ezra handed over control of Mongbwalu to FNI Commanders Mutakama and Butsoro as Ugandan army troops left the area. All parties signed the document, witnessed by MONUC observer Oran Safwat.105 Although Commander Jérôme and most of his troops had withdrawn to Aru, a contingent under Commander Sey remained at Mongbwalu.

Witnesses also said that Ugandan army commanders left behind some of their ammunition and weapons for the FNI.106 In addition, a shipment of Ugandan arms bound for Mongbwalu was seized by MONUC in Beni several months after the Ugandans withdrew. Those accompanying the arms reported that the FNI were still getting aid from Uganda and that the weapons seized in Beni were meant for them. According to the MONUC report on the incident, one of those accompanying the weapons, a deputy administrator from Mongbwalu, admitted he was constantly in touch with the Ugandans.107

Accountability for the March 2003 Kilo Massacre

Many witnesses reported the abuses to local authorities who in turn wrote a letter to the MONUC human rights section in Bunia on September 26, 2003 listing 125 civilian deaths, cases of torture and rape in the Kilo area from March to May 2003 carried out by FNI combatants while Ugandan soldiers were still present in the area.108 No response was received and on November 20, 2003 a second letter was sent detailing a further nineteen deaths, eight cases of torture and two cases of rape between July to November 2003.109

The Ugandan army had command control over the FNI combatants during their joint military operation and should be held responsible for the abuses committed by FNI combatants. Although they may have attempted to minimize crimes by organizing joint patrols and requesting that combatants lay down their traditional weapons, they did not carry out any further steps to ensure accountability for these crimes. In addition, they soon armed the FNI with modern weapons. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any investigation or arrest made by either the Ugandan army or the FNI authorities into abuses committed by their troops. To date no one has been held responsible for the massacre of civilians and other serious human rights abuses committed in Kilo.

The 48 Hour War, June 2003 and subsequent massacres

After the Ugandan forces left in May 2003, the UPC retook Mongbwalu on June 10, 2003. Despite having recently received additional weapons from Rwanda, delivered at a newly constructed airstrip some 30 kilometers from Mongbwalu,110 the UPC was able to hold the town for only forty-eight hours before being pushed back by the FNI combatants under the command of Mateso Ninga, known as Kung Fu. The FNI counter attacked with heavy weapons that had reportedly been left behind by the Ugandans.111 For the Lendu, their victory in what became known as the “48 Hour War,” was a source of great pride. Based on local testimony, it appears that some 500 persons were killed during the Lendu counterattack, many of them civilians.112

FNI authorities asserted that the UPC attacked Mongbwalu in order to regain control of the gold.113 In addition, a large number of civilians accompanied the combatants, apparently intent on looting and helping the combatants loot the town.114 According to witnesses and FNI authorities, they represented a large number of those killed during the Lendu counterattack.115 One witness recounted being shocked at the sight of so many bodies, civilians as well as combatants, in town on the day of the Lendu victory. He said,

[Commander] Kung Fu saw that many people died and he asked people to help with burying. But there were too many so they just decided to burn them instead. They burned for at least three days. There was a terrible smell in the air.116

FNI officials acknowledged to a Human Rights Watch researcher that civilians had accompanied the UPC combatants.117 During a commemorative re-enactment of the battle at 2004 May Day celebrations in Mongbwalu stadium, witnessed by Human Rights Watch, women and young people playing the role of Hema civilians were portrayed carrying goods before they were killed by Lendu combatants under the command of Kung Fu. The play went on to show the community burning the bodies of those killed and declaring Commander Kung Fu a hero.118 But when questioned on the issue, the self-styled president of the FNI, Floribert Njabu, asserted that there had been no civilians with the attacking combatants. He declared that the FNI had “professional commanders who know about the international rules of war”119 implying they would not have killed civilians.

There is no evidence to suggest that the FNI combatants distinguished between military and civilian targets during the battle. According to local reports and witnesses the killing was indiscriminate and did not distinguish women and children from combatants. While it is not unusual for women and children to take part in looting activities in such military operations in Ituri, they should have been respected.

Shortly after retaking Mongbwalu from the UPC, FNI combatants continued their attacks against Hema civilians. Between July and September 2003, FNI combatants attacked numerous Hema villages to the east of Mongbwalu including Nizi, Drodro, Largo, Fataki and Bule. In the town of Fataki a witness arriving shortly after one such attack by FNI combatants reported seeing the fresh corpses of victims dead in the streets with their arms tied, sticks in their rectums, and body parts such as ears cut off.120 In Drodro witnesses reported that FNI combatants attacked the hospital shooting Hema patients in their beds.121 Local sources claimed scores of civilians had been killed in these attacks and thousands of others were forced to flee. A stark warning was left behind by the attackers etched on the wall of a building in Largo, “Don’t joke with the Lendu.”122

There was a substantial MONUC presence in Ituri at the time as well as European Union peacekeeping troops as part of Operation Artemis.123 No U.N. officials reported on the killings in Mongbwalu in June 2003. U.N. and E.U. troops were made aware of the later killings in areas to the east of Mongbwalu by international journalists who had visited the area and conducted fly-over operations in attempts to deter further violence. The Artemis mandate granted by the U.N. security council did not allow for peacekeeping actions outside of the town of Bunia.

A ‘Witch Hunt’ for Hema Women and other Opponents

Shortly after the UPC attack in June 2003, FNI combatants began accusing Hema women living in and around Mongbwalu of spying for Hema armed groups. Hema women still living in the area were few in number and most of them were married to Lendu spouses and had been able to live safely within the Lendu community. But after the “48 hour war” Lendu combatants arrested, tortured and killed these women and some men, accusing them of ‘dirtying and betraying’ their society. Using charges of witchcraft, Lendu combatants and spiritual leaders covered their crimes by claiming the killings had been ordered by a spirit known as Godza. More moderate FNI officials found it difficult to counter these claims and did nothing to stop them. A witness said,

After the June [2003] attack, the Lendu decided to kill all the Hema women without exception. There were women I knew who were burned. I had never seen that kind of thing before. Previously Hema women who were married to outsiders were not harmed. Now they wanted to hunt these women. The Lendu spirit, Godza, told them to kill all the Hema women during one of the Lendu spiritual ceremonies. One of the women they killed was Faustine Baza. I knew her well. She was very responsible and lived in Pluto. The FNI came to get her and took her to their camp. They killed her there. They killed other women as well. I did not want to be a part of this so I left. I couldn’t stay while they were exterminating these Hema women. They did it in Pluto and Dego. They came from Dego with thirty-seven Hema women to kill. I don’t want to return now - it’s too hard.124

Another witness said,

In July women were killed at Pluto and Dego. The strategy was to close them in the house and burn it. More than fifty were killed. Pluto was considered the place of execution for Hema people from Pluto and other places too. They captured the women from the surrounding countryside. They said it was to bring them to talk about peace. They put ten women in a house, tied their hands, closed the doors, and burned the house. This lasted about two weeks, with killing night and day. After that, no more Hema women were left in [our area] and the men were prevented from leaving with their children. They called the women “Bachafu” – dirty. Sometimes the men would be taken to prison. Suwa’s husband was asked to pay $300. They told him they killed his wife, and he had to pay thirty grams of gold ($300) to clean the knife they had killed her with.125

Many people were aware of the killings and bodies were often seen in the towns. A witness reported seeing six bodies of women at the Club, a well-known building in Mongbwalu, in mid-2003. He said many other passers-by also saw the nude and brutalized bodies and that Lendu combatants were trying to recruit people to help burn them.126 A community leader in an outlying village expressed his frustration about the continuation of the practice, saying he had been interrogated more than ten times by Lendu combatants as to the whereabouts of Hema women. He said to a Human Rights Watch researcher, “I want to know what Kinshasa is going to do to help us. Are they going to let the FNI stay here? The population is really suffering.”127

The operation against Hema women extended to men and other tribes as well and continued at least until April 2004, killing some seventy persons in Pluto, Dego, Mongbwalu, Saio, Baru, Mbau and Kobu and possibly in other locations in the Mongbwalu area. By this point, the allegation of witchcraft became a common accusation, often resulting in death after a ‘judging ceremony’ by local spiritual leaders. Carried out in secret these judging ceremonies used different methods to determine a person’s guilt or innocence. One civilian accused of being Hema described to a Human Rights Watch researcher the ceremony he and others were forced to undergo after being caught by Lendu combatants in 2003:

A local fetisher [spiritual leader] came to the place I was being held. He had two eggs with him. I was tied up and very scared. He rolled the eggs on the ground at my feet. I was told if the eggs rolled away from me then I would be considered innocent. But if the eggs rolled back towards me than I was considered to be a Hema and I would be guilty. I was lucky, the eggs rolled away from me. Another person, Jean, who I was with, was not so lucky. The eggs rolled the wrong way and he was told to run. As he ran the Lendu shot their arrows at him. He fell. They cut him to pieces with their machetes in front of my eyes. Then they ate him. I was horrified.128

In the Mongbwalu area the killings continued throughout 2003 and into 2004. A witness described to a Human Rights Watch researcher the ongoing killings:

[After the June war] they said they did not want the Hema to return. Those who stayed were killed. They killed them in Saio and Baru. They would just take them away. A man called Mateso, Bandelai Gaston, a Nyali, and his brother Augustin were killed because they were accused of being witches. There were also women who were killed. Celine, an Alur, was killed for witchcraft. Gabriel, a Kakwa, and his wife were also killed. They were accused of protecting Hema people.129

Some community leaders raised concerns about the ‘Godza ceremonies’ with FNI leader Njabu, in July 2003. At the time he seems to have done nothing to stop the killings, but according to local residents, the number decreased after he moved to Mongbwalu in February 2004, whether simply as a coincidence or as the result of his presence is unclear.130

While some FNI authorities may have been against such killings, and perhaps took steps to minimize them, at the time of writing no one has been held responsible for them. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any investigation carried out by FNI representatives into these killings.

Murder of two MONUC Observers

On May 12, 2003, shortly after Ugandan troops had left Mongbwalu to the FNI and the FAPC, FNI combatants deliberately killed two unarmed U.N. military observers, Major Safwat Oran of Jordan and Captain Siddon Davis Banda of Malawi. Rumors of an impending Hema attack—which would actually happen with the “48 hour war” a month later—caused panic among town residents, about one hundred of whom sought refuge at the residence of the MONUC observers. The observers, apparently concerned themselves, arranged to be evacuated. When the U.N. helicopter arrived at a nearby airstrip, FNI combatants refused to allow the observers to pass. Led by FNI Commander Issa, the combatants took them to FAPC Commander Sey at his headquarters at the “apartments.” “The combatants were chanting that Sey should not let them leave,” said one witness.131

Shortly after, the combatants led the observers away again, apparently because Sey declined to take them under his protection, and killed them a short distance from the “apartments.” A witness who passed by later that afternoon said,

I found the bodies on the road leading down from the apartments. They had both been shot. One was shot in the head and the other in the stomach. I found the military of the FAPC around the bodies.132

Local residents transported the bodies to the FAPC headquarters and placed them in a nearby empty house. Sey and his combatants fled from Mongbwalu that evening, apparently seeking to distance themselves from the crime.133 Local residents later buried the two bodies in a shallow grave in Mongbwalu.134

According to several Mongbwalu residents, FNI Commander Issa was responsible for the killings. Witnesses reported that FNI combatants took possession of the observers’ U.N. cars and used them until they were recovered by the U.N.135

During discussions with a Human Rights Watch researcher, the FNI’s leader Njabu said, “We did not investigate the killings. It is not our affair. Our military were at Saio at the time, seven kilometers away. Commander Jérôme’s combatants were at the apartments. You should ask Commander Sey what happened.”136 But in a second interview days later he admitted that Commander Issa might also have been present and he indicated that an investigation was ongoing.137 More than one year later, FNI authorities had not yet announced any results of an investigation. According to one unconfirmed local report, FNI Commander Kung Fu did carry out an investigation and, presumably as a result, Commander Issa fled and was reportedly later killed.138

Threat Against Human Rights Defenders and Others Reporting Abuses

Some FNI combatants tried to keep local people from being in touch with MONUC or other outside agencies, apparently for fear that they would pass on information about FNI abuses.

Important FNI commanders threatened human rights activists from the organization Justice Plus after they had traveled to Europe and spoken about the situation in Ituri.139 Other FNI leaders reportedly planned to look into activities of the organization and threatened that its staff would be considered enemies if they were found to have had contacts with the Rwandans and the Hema.140

FNI combatants acted more directly and immediately against local residents known to have spoken with MONUC staff during their occasional visits to Mongbwalu in late 2003.141 One person so abused said,

I was taken by nine [Lendu] combatants in uniform. They came to my house and shouted, “Get up! What did you say to MONUC?” They threatened me with their spears. They took me to the apartments and I was interrogated by [a Lendu commander]. He asked me what I had said to MONUC. That is all he wanted to know. He threatened me. They hit me on the face. I said I had told MONUC nothing. They said they would put me in prison. They took $100 from me but a commander who knew me saved me and they let me go.142

The same person was arrested a second time and severely beaten with bats and ropes. He was kept for seven days and regularly beaten.143

Witnesses reported that civilians were threatened for having applauded visits of MONUC staff.144 After one such mission in November 2003, some twelve civilians were beaten and arrested, and at least one, a man named Choms, was summarily executed. A witness told a Human Rights Watch researcher that Mr. Choms had applauded the arrival of a U.N. plane, saying he thought this meant peace was coming. Local police reported this to the FNI and two combatants of the force arrested Mr. Choms and another person and took them to the police station. A witness who went to the police station the next day to check on Mr. Choms said,

The other prisoners told me he had been interrogated and beaten and that this was followed by a shot. . . . I forced my way into the room and the body was still there. He had no shirt on and there was a bullet in his chest. He had marks on his back from being whipped. They then questioned me and forced me to leave. They wouldn’t give us the body for burial.145

Arbitrary Arrests, Torture and Forced Labor

FNI combatants imposed a number of “taxes,” collected in an arbitrary and irregular way, and organized forced community labour known as “salongo”. FNI representatives resorted to arbitrary arrests, beatings, and other forms of cruel and degrading treatment to obtain the maximum possible payment and service from civilians. According to local residents, these practices worsened considerably after the departure of Ugandan troops.146

Residents were required to pay a “war tax” that varied in amount and in the frequency with which it was due.147 Traders at the market were also subject to confusing and irregular “tax” demands. One businessman said,

There are about five or six different taxes. They range from $2 to $20. Everyone has to pay. You pay when they come and sometimes they come back again after just a few days. It is very irregular. If you don’t pay you are beaten or taken to prison. . . . Both military of the FNI and civilians do this.148

Human Rights Watch researchers documented similar abusive cases throughout the Mongbwalu area, Kilo, Rethy and Kpandruma. “The people can say or do nothing,” said one witness. “We just do what the FNI say.”149

A young trader arrested on February 5, 2004 by the FNI for non-payment of tax was beaten and taken to the Scirie-Abelcoz military camp. He said,

There I spent two days in. . . a hole in the ground covered by sticks. They took me out of the hole to beat me. They tied me over a log and then they took turns hitting me with sticks – on my head, my back, my legs. They said they were going to kill me.. . .There was a woman with me in the underground prison. They hit her also. They tried to force me to have sex with her but I couldn’t. She was called Bagbedu.

After two days I was taken to Mongbwalu. They made me carry the woman and forced me to sing songs as I was carrying her. I was escorted by three FNI combatants and one kadogo [child soldier]. On the road, we met other soldiers who forced me to drop the woman and beat me more. In Mongbwalu the soldiers beat me again with sticks. They took me to a prison in a house. They also put the woman in the prison but she died four days later. I spent five days there. Every day they beat me.150

After a week, his family paid $80 and Commander Maki of Camp Goli freed him.

FNI representatives showed a Human Rights Watch researcher a long list of taxes asked of residents, including a “war tax” that they claimed was voluntary.151

The FNI used similar practices to enforce the salongo policy of community labour to fix roads, collect firewood for the military, clean up the military camp, or even burn bodies as described above. At times salongo was required for as much as two full days a week, although by late 2004 it had been decreased to once a week for three hours. Participants received a piece of paper showing they had done the required labour. Persons who could not present such proof when asked by police or combatants were subject to beatings, arrest, fines or even death. According to one witness, a young man named Lite who failed to present the required proof when asked was smashed in the head with a gun by a FNI combatant and died from the blow. The witness asked FNI authorities what justice there would be for the family of Lite and, he said, “They responded that the family of Lite could kill the man who had done this act, but the family would not.”152

Young gold trader arrested and tortured in Mongbwalu in February 2004 by

Lendu FNI combatants for being unable to pay a market tax. © 2004 Human

Rights Watch

Another man reported that he was rounded up with a group of about one hundred men who had all refused to report for salongo labour some fifteen miles from their homes, saying it was too far. They were forced to walk all night and then were imprisoned and had to pay $5 for each elderly person, $10 for each young person, and $20 for each businessman in order to be freed.153

A local administrative official admitted that in order to get laborers for salongo they needed to “intimidate people to come, otherwise they would not.”154 A person responsible for the salongo in Saio told a Human Rights Watch researcher that the local chief would “deal with people who don’t work,” while a police commander added that he “sanctioned those who refused to work.”155 He would not elaborate on what kind of sanctions were involved.

Control of the Gold Mines

Upon taking control of Mongbwalu on March 13, 2003, the FNI militia leaders, like the UPC previously, moved immediately to begin profiting from gold mining. Artisanal miners resumed digging, but had to pay FNI combatants fees to enter the mines, $1 per person at some mines. Based on entrance records kept by FNI security guards at one mine and seen by Human Rights Watch researchers, the FNI made $2,000 per month in entrance fees at this one mine alone.156 Miners also had to deliver to FNI two to five grams of gold per week, often as raw ore. From such ore FNI combatants were able to assess the density of the gold and thus to locate the most valuable veins. They could then send in their own men to mine those areas.157 As one miner said,

The money that circulates in Mongbwalu is gold. Gold is the economy.

The Lendu take the gold from the diggers. They take the best gold areas by force. Lots of people don’t want to go and dig for gold as they know it will be taken from them.158

FNI combatants, some of them previously gold diggers, also mined gold themselves or organized groups of people to dig for them. In Itendey, a gold area just to the south of Mongbwalu, for example, FNI combatants forced young men to mine gold in a nearby riverbed. A local community leader who had fled from the area told a Human Rights Watch researcher,

The FNI combatants come every morning door-to-door. They split up to find young people and they take about sixty of them to the Agula River to find the gold. They [the young people] are guarded by the military and are not paid. They are forced to work. If the authorities try to intervene they are beaten. The chief has tried to stop this by reasoning with them, but they don’t like this. They even force the younger children to leave school to carry sand or transport goods.159

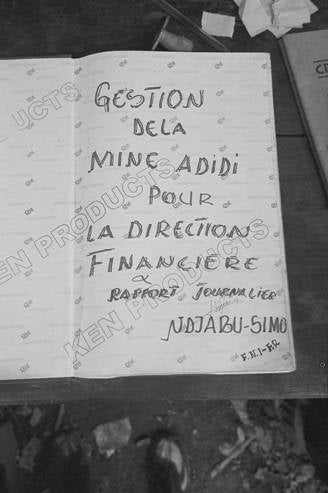

Entrance register kept by FNI security guards at Adidi gold mine

(“Management of Adidi mine for the financial management and daily report,

Ndjabu-Simo, FNI-FR”). Each gold miner paid US$1 to enter the mine and was

forced to give a portion of the mined gold to the guards when exiting. © 2004

Human Rights Watch

Miners worked in deplorable conditions, exposed to risk of accidents both in the mines and when handling mercury to process the ore.

|

Box 2 - Conditions at the Mines In May 2004 a Human Rights Watch researcher visited mines in Mongbwalu and Durba where many miners and engineering experts spoke of the deteriorating safety conditions at the mines. One former OKIMO engineer told Human Rights Watch about the lack of air in parts of the underground mine where equipment that used to ensure oxygen flows was no longer working. Miners recounted that some of their colleagues had died of suffocation in parts of the mine, especially when fires were lit in attempts to soften hard rock areas, a technique witnessed by Human Rights Watch researchers.160 Miners also spoke of frequent rocks falls, flooding and other accidents. No safety equipment of any kind was visible. Miners worked individually or in small groups with rudimentary tools such as hammers and chisels. They were generally in bare feet and carried candles or small flashlights to light their way. In some underground mines, workers walked for kilometers through chest-high water and narrow passages to get to galleries where they could work. Women also worked in the mines often being used as porters. Mining in open-pit mines, some as deep as 300 meters, is also precarious. Miners spoke of frequent mud-slides and falls. Expert gold engineers lamented the anarchic mining that was taking place with no regard for the safety of the miners themselves or for the longer term damage being caused to the mining facilities.161 One miner said, “There are some areas which were boarded up by the Belgians many years ago. But we just break down the boards and go in anyway. We use a hammer and a large iron bolt or chisel to dig for the gold. The work is very hard and I could only work about six hours per day.”162 Miners, if they are lucky, get about $10 per day. One miner said, “I can make between $5 and $20 per day if I am lucky and find a good gold vein. Otherwise I could work for 2 weeks just looking for gold and make nothing.163 When asked why they worked in such dangerous conditions, one miner responded, “Tell me what choice I have? This is the only way I can make any money. Its about my own survival and that of my family.”164 The entire mining and refining process is done by hand. After the ore is mined, it is pounded down into sand with the use of an iron bar. The sand is then mixed with water and mercury, which attracts the gold particles and separates it from the rock dust. The mixture of gold and mercury is then heated so the mercury evaporates and the gold remains. Mercury, a dangerous substance, is readily available in the market areas. Human Rights Watch witnessed numerous miners using mercury with no gloves or masks, taking no safety precautions when handling the substance. |

In addition to profiting directly from mining, FNI leaders sought to control the trade in gold. According to gold traders, FNI control of the trade was still haphazard and sometimes involved direct use of force. In May 2004, the FNI Commissioner of Mines explained to a Human Rights Watch researcher that the FNI were well aware of the significance of the gold market in Mongbwalu and that “they were looking for additional ways to control the trade.”165 There are no reliable statistics on the amount of the gold trade from Mongbwalu nor of the proceeds reaped by the FNI from it. Local traders and other informed sources estimated that between 20 and 60 kilograms of gold left the Mongbwalu area each month, a value of between $240,000 to $720,000 per month at the time of writing. The majority of the gold is traded from Mongbwalu to Butembo in North Kivu where Dr Kisoni Kambale is one of the main gold exporters (see below).

As one gold miner explained, “The profits enter into the pockets of the FNI,”166 both in the sense of personal profit and in the sense of profit to the FNI. A former senior FNI commander told a Human Rights Watch researcher that some of the gold proceeds were used to buy weapons and ammunition to supplement weapons recuperated from the battlefield.167 The leader of the FNI, Njabu, himself admitted to Human Rights Watch researchers that his combatants mined gold and that he traded gold for weapons. He calculated the proceeds he would make from the sale of five kilograms of gold to be about $50,000, adding “This is not looting as I am Congolese.”168 A MONUC investigation into weapons seized in Beni in July 2003 confirmed that the FNI used taxes from the gold mines to buy weapons.169 Njabu admitted to a Human Rights Watch researcher that he had purchased these weapons, adding, “I want them back or I will fight to get them.”170

The FNI armed group was also approached by multinational companies eager to gain access to the significant gold reserves in the area. The FNI Commissioner of Mines explained to Human Rights Watch that they had been approached by a number of different companies but that officially AngloGold Ashanti had the concession in the Mongbwalu area and that they were in contact with them (see below for further information).171 The arrival of multinational companies into a volatile area where conflict and competition for the control of natural resources are closely interlinked creates further complexities and has the potential to create more violence. While AngloGold Ashanti is the only mining company working in the Mongbwalu area, other companies have signed contracts for work in gold mining areas further north in the town of Durba.

[49] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 1, 2004.

[50] Ibid., Panel of Experts, “Confidential Supplement to the U.N. Security Council”, November 2003.

[51] Human Rights Watch interviews Mongbwalu, Bunia, Kinshasa, February and May 2004. Also Letter from OKIMO Director General, Etienne Kiza Ingani to Thomas Lubanga, President of the UPC. Ref DG/SDG/172/2002, October 1, 2002. Annex, “The Expectation of OKIMO”, October 2002.

[52] Letter from OKIMO Director General, Etienne Kiza Ingani to Thomas Lubanga, President of the UPC. Ref DG/SDG/172/2002.

[53] Human Rights Watch interview, OKIMO employee, Mongbwalu, May 4, 2004.

[54] Human Rights Watch interview, former combatant, Mongbwalu, May 4, 2004.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid., Panel of Experts, “Confidential Supplement to the U.N. Security Council”, November 2003.

[57] Human Rights Watch interview, Beni, February 27, 2004.

[58] Human Rights Watch interview, Oicha, February 2003.

[59] Justice Plus interviews, Ituri, March 2003.

[60] Human Rights Watch interview, Beni, February 27, 2004.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 2, 2004.

[63] Human Rights Watch interview, Oicha, February 2003.

[64] Human Rights Watch interviews, Mongbwalu and Bunia, May 6 and October 8, 2004.

[65] Lendu combatants sometimes wear traditional arm bands or necklaces known as ‘grigri’ that they believe ward off harm and protect them against attackers.

[66] Human Rights Watch interview, village near Mongbwalu, May 6, 2004.

[67] Ibid., United Nations Security Council, "Special Report on the Events in Ituri”, p. 24.

[68] It is nearly impossible to get accurate statistics on death rates. It is possible the death toll of civilians could be much higher.

[69] Human Rights Watch interview, displaced persons camp, Beni, February 27, 2004.

[70] For more information on similar conduct by UPC in Bunia, see Human Rights Watch, “Ituri: Covered in Blood”, July 2003. Also United Nations Security Council, “Special Report on the Events in Ituri”, p. 34 – 38.

[71] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 2, 2004.

[72] Human Rights Watch interview, Oicha, February, 2003.

[73] In total three nuns and five priests have been killed since 1999 in Ituri. The most recent one was killed in Fataki in August 2003. According to Catholic Church officials, two Hema priests killed in Bunia in May 2003 by Ngiti and Lendu combatants may have been targeted in retaliation for the killing of Abbé Bwanalonga. Human Rights Watch interview, Catholic Church officials, Bunia, May 10, 2004.

[74] Human Rights Watch interview, Catholic Church officials, Bunia, May 10, 2004.

[75] Human Rights Watch interview, Bunia, February 2003.

[76] “UPC Rebels Grab Mongbwalu’s Gold”, African Mining Intelligence No. 53, January 15, 2003.

[77] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 4, 2004

[78] Human Rights Watch interview, OKIMO employee, Mongbwalu, May 4, 2004

[79] Human Rights Watch interview, Bunia, February 2003.

[80] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 2, 2004.

[81] Human Rights Watch interviews, Mongbwalu, May 2, 2004; Bunia, February 2003.

[82] Human Rights Watch interview, former gold miner, Oicha, February 2003.

[83] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 1, 2004.

[84] Human Rights Watch interview, Ariwara, March 7, 2004.

[85] Ibid.

[86] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 1, 2004.

[87] Ibid.

[88] Ibid., Panel of Experts, “Confidential Supplement to the U.N. Security Council”, November 2003.

[89] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 2 and 4, 2004.

[90] Human Rights Watch interview, MONUC human rights section, Bunia, February 20, 2004.

[91] Donors involved in security sector and army reform in the DRC include the Belgian and South African governments and the European Union.

[92] Ibid., 0 Nations Security Council, “Special Report on the Events in Ituri”, p13

[93] Human Rights Watch interview, former Lendu militia leader, February 21, 2004.

[94] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 4, 2004.

[95] Human Rights Watch interview, local analysts, Bunia, October 10, 2004. Also Human Rights Watch interview, Floribert Njabu, President of the FNI, May 2, 2004.

[96] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 5, 2004.

[97] Human Rights Watch interview, Bunia, February 24, 2004.

[98] Human Rights Watch interview, local analysts, Bunia, October 10, 2004. Also Human Rights Watch interview, Floribert Njabu, President of the FNI, May 2, 2004.

[99] Human Rights Watch interview, Bunia, February 23, 2004.

[100] Human Rights Watch interview, Bunia, February 24, 2004.

[101] Human Rights Watch interview, local authorities, Bunia, October 8, 2004.

[102] Letter from Brigadier Kale Kayihura to the Regional Director of MONUC in Bunia, RE: Disposition of UPDF in the Two Command Sectors of Bunia and Mahagi., April 17, 2003. The document also confirms that 1 Infantry Coy was left in Kilo.

[103] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 2 and 4, 2004.

[104] Ibid.

[105] UPDF Restricted Document, “Withdrawal of Ugandan Peoples’ Defence Forces from the Democratic Republic of Congo,” UPDF Form No. AC/DRC/01 signed in Mongbwalu, May 1, 2003. Document on file at Human Rights Watch.

[106] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 2, 2004.

[107] Confidential U.N. internal report on the investigation into the plane seizure in Beni, July 25, 2003.

[108] Letter from local authorities to MONUC Human Rights Section in Bunia, “Transmission of report on the tragic events carried out by Lendu combatants in Banyali/Kilo from March 9, 2003 till present against the civilian population”, Ref No 323/09/1,180/2003, September 26, 2003.

[109] Letter from local authorities to MONUC Human Rights Section in Bunia, “Table of Human Rights Violations in B/Kilo Sector”, Ref No 323/21/1,180/2003, November 20, 2003.

[110] Ibid., Panel of Experts, “Confidential Supplement to the U.N. Security Council”, November 2003.

[111] Human Rights Watch interviews, FNI authorities, Mongbwalu, May 2, 2004 and local residents, May 3, 2004.

[112] Human Rights Watch interviews, Beni and Mongbwalu, February 27 and May 2, 2004.

[113] Human Rights Watch interview, FNI authorities, Mongbwalu, May 2, 2004.

[114] Human Rights Watch interview, Beni, February 27, 2004.

[115] Human Rights Watch interviews, Beni and Mongbwalu, February 27 and May 2, 2004.

[116] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 1, 2004.

[117] Human Rights Watch interview, FNI officials, May 2, 2004.

[118] May Day Celebrations, Mongbwalu Stadium, May 1, 2004 attended by a Human Rights Watch researcher.

[119] Human Rights Watch interview, President Floribert Njabu of the FNI, Mongbwalu, May 7, 2004.

[120] Human Rights Watch interview, international journalist, London, January 12, 2005.

[121] Ibid., See also Helen Vesperini, “DR Congo villagers reel from second massacre in four months,” Agence France Presse, July 27, 2003.

[122] Ibid.

[123] Operation Artemis was the name of the Interim Emergency Multinational Force sent by the European Union and authorised by the U.N. Security Council under Resolution 1484 on May 30, 2003 to contribute to the security conditions and improve the humanitarian situation in Bunia. It was a limited three month mission with a geographical scope to cover only the town of Bunia.

[124] Human Rights Watch interview, Beni, February 27, 2004.

[125] Human Rights Watch interview, Beni, February 27, 2004.

[126] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 2, 2004.

[127] Human Rights Watch interview, village outside Mongbwalu, May 6, 2004.

[128] Human Rights Watch interview, Arua, Uganda, February 2003.

[129] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 5, 2004.

[130] Human Rights Watch interviews, Mongbwalu, May 2 and May 4, 2004.

[131] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 4, 2004.

[132] Ibid.

[133] Human Rights Watch interview Mongbwalu, May 5, 2004.

[134] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 4, 2004.

[135] Human Rights Watch interview, Bunia, and Mongbwalu, February 19 and May 4, 2004.

[136] Human Rights Watch interview, FNI President Floribert Njabu, May 2, 2004.

[137] Human Rights Watch interview, FNI President Floribert Njabu, May 7, 2004.

[138] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 5, 2004.

[139] Human Rights Watch interview, Justice Plus, Bunia, February 24, 2004.

[140] Human Rights Watch interview, Justice Plus, Bunia, February 24, 2004.

[141] After the killing of the two MONUC observers, no other MONUC staff were posted to Mongbwalu until April 2005.

[142] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 4, 2004.

[143] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 4, 2004.

[144] Ibid.

[145] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 5, 2004.

[146] Human Rights Watch interview, local residents, Mongbwalu, May 3 and 4, 2004.

[147] Ibid.

[148] Human Rights Watch interview, Ariwara, March 7, 2004.

[149] Human Rights Watch interview, Bunia, February 20, 2004.

[150] Ibid.

[151] Human Rights Watch interview, Jean Pierre Bikilisende Badombo, Chef de Cité and Sukpa Bidjamaro, Deputy Chef de Cité, May 3, 2004.

[152] Human Rights Watch interview, Bunia, February 23, 2004.

[153] Human Rights Watch interview, Ariwara, March 7, 2004.

[154] Human Rights Watch interview, Mongbwalu, May 4, 2004.

[155] Human Rights Watch interview, Manu Ngabi, local authority and Gerard Kitabo, Police Commander, Saio, May 5, 2004.

[156] Human Rights Watch visit to Adidi mine, May 3, 2004. Statistics from the entrance book kept by FNI security officials at the entrance mine. Book clearly labeled as FNI.

[157] Human Rights Watch interview, Bunia, February 23, 2004.

[158] Human Rights Watch interview, Beni, February 25, 2004.

[159] Human Rights Watch interview, Bunia, February 20, 2004.

[160] Human Rights Watch interview, former gold engineer, Mongbwalu, May 2, 2004. Also Human Rights Watch visit to Adidi and Makala mines, Mongbwalu, May 3, 2004.

[161] Human Rights Watch interview, OKIMO engineer, Durba, May 13, 2004.

[162] Human Rights Watch interview, gold miner, Bunia, February 21, 2004.

[163] Ibid.

[164] Human Rights Watch interview, gold miner, Mongbwalu, May 2, 2004

[165] Human Rights Watch interview, Mr. Basiani, FNI Commissioner of Mines, May 5, 2004.

[166] Human Rights Watch interview, gold miner, Bunia, February 23, 2004.

[167] Human Rights Watch interview, former FNI commander, Bunia, February 21, 2004.

[168] Human Rights Watch interview, FNI President Floribert Njabu, Kinshasa, October 7, 2003.

[169] U.N. internal report on the investigation into the plane seizure in Beni, July 25, 2003.

[170] Human Rights Watch interview, FNI President Floribert Njabu, Kinshasa, October 7, 2003.

[171] Human Rights Watch interview, Mr. Basiani, FNI Commissioner of Mines, May 5, 2004.

| <<previous | index | next>> | June 2005 |