<<previous | index | next>>

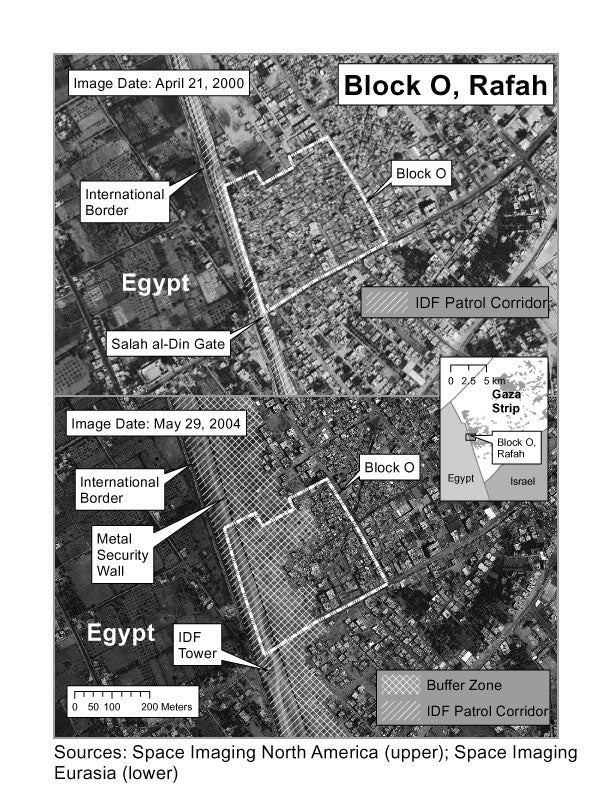

Map 3: Buffer Zone Expansion

The western side of O Block (facing the border) is 350 meters in length. In April 2000 the IDF patrol corridor measured an average of thirty-three meters in width, from the border with Egypt to the concrete wall at the edge of Block O. In total the satellite imagery comparison of Block O between April 2000 and May 29, 2004 shows that 60% of this area of Rafah was damaged. Ground-level assessments by Human Rights Watch researchers indicate extensive damage that is not discernible at two-meter resolution.

Starting in 2003, Block J became another major focus of destruction, with at least 225 homes demolished there. Demolitions have also spread to border neighborhoods such as Salam, Block L, and Qishta.

New Realities: Widening the Buffer Zone

The need for a buffer zone empty of Palestinians in Rafah is not a new concept in Israeli strategic doctrine, which has often emphasized the importance of retaining the external boundaries of the OPT in any final peace agreement. While head of the IDF Southern Command in the early years of the occupation, General Ariel Sharon proposed the creation of settlements (which he referred to as “Jewish fingers”) to break up the territorial contiguity of Palestinian cities in the Gaza Strip and thus strengthen Israel’s control over the area. He also believed that “it was essential to create a Jewish buffer zone between Gaza and the Sinai [then under Israeli control] to cut off the flow of smuggled weapons and – looking forward to a future settlement with Egypt – to divide the two regions.”150 Although the “disengagement” plan would necessitate an abandonment of the Gaza settlements, the idea of the buffer zone along the border remains and is being gradually implemented.

In more recent years, high-level Israeli officials have spoken publicly of the need to expand the buffer zone by destroying all houses within a certain distance of the border. Increasing the distance between the homes and the border would make attacks on patrols and tunneling more difficult, they say.

Under international law, an Occupying Power may take a wide range of measures to improve its general security, including building fortifications and restricting movements of the civilian population, but destruction must be linked to combat. Border patrol operations by themselves are not by themselves combat operations. Even if fighting in a particular area of the border reaches a level of regularity equivalent to an ongoing state of hostilities, the IDF is permitted to attack only those specific homes that were making an effective contribution to military action and whose destruction would have offered a definite military advantage. In cases of doubt, under international humanitarian law, objects normally dedicated to civilian purposes, such as houses, are presumed not to be military objectives.151 Destroying homes simply because they are within weapons range of IDF positions is accordingly unlawful. Given the evidence presented that the homes were mostly inhabited, these areas retain their overall civilian character and cannot be lawfully razed wholesale.152

In January 2002, the IDF demolished a group of houses in Block O, the largest destruction operation during the uprising until that time. Twenty-one “mostly uninhabited” buildings were torn down and one tunnel was found, said Major-General Doron Almog, head of the IDF Southern Command at the time and responsible for operations in the Gaza Strip.153 But UNRWA, PCHR, and the Israeli human rights organization B’tselem estimated that approximately sixty houses had been destroyed and they presented evidence that most were inhabited at the time.154 The international community largely saw the demolitions as retaliation for the killing of four Israeli soldiers the previous day by Hamas at an outpost more than eight kilometers outside of Rafah, at Kerem Shalom near the Gaza Strip. Israeli officials repeatedly insisted that the demolitions had been planned weeks earlier and were unconnected to this attack.155

At the time, senior military officers were frank about the need to expand the buffer zone and to destroy houses as a precautionary security measure. According to Major-General Almog, the operation served several purposes:

The direct intentions of this operation were to weaken the fear of the existence of tunnels underneath the Termit post, to create better observation [of?] territories for the forces and to limit the mobility of the terrorists who are trying to approach the road and injure IDF soldiers. The need to expose and to enlarge the IDF’s area of activity of operations on the Philadelphia became grater [sic] since the beginning of the current events, there is no doubt about that, the question is concerning the timing. On the same Saturday a tunnel was found which proves operational necessity that exists there all the time.156

Almog’s predecessor as head of the Southern Command, Major-General Yom-Tov Samiya, was more blunt. Samiya reportedly gave an interview on Israeli radio in which he spoke of demolitions as a “long-term policy.” He also advocated acts of collective punishment, which are strictly prohibited under international humanitarian law157:

The IDF has to pull down all the houses along a 300-400 meter strip. No matter what the final settlement will be in the future, that will be the border with Egypt. … Arafat should be punished and after every attack, two to three rows of houses should be demolished.158

After five soldiers were killed in an APC near Block O on May 12, 2004, the idea of widening the buffer zone was again publicly discussed in Israel, from the highest levels of government down.

The day after the incident, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, Defense Minister Shaul Mofaz159, and other officials approved a plan to demolish “dozens or perhaps hundreds” of homes to widen the corridor three hundred meters or more. According to one unnamed Israeli official, “It’s a measure that we are taking to provide better protection for armored personnel carriers and the soldiers, and to reshape that theatre of war so we will enjoy an advantage and not the Palestinians.”160 In a cabinet meeting on May 16, IDF Chief of Staff Lieutenant-General Moshe Ya’alon reportedly spoke of the need to demolish hundreds of homes, while Mofaz said that Israel would create a “new reality” along the border.161

In an unambiguous statement of policy, an IDF briefing document on Rafah tunnels announced, “In order to prevent weapons smuggling, the IDF is widening the Philadelphi route in order to maintain the integrity of the internationally recognized border, to prevent terrorism, and to protect Israelis and Palestinians from terrorism.”162

As international criticism over IDF actions in Rafah peaked, the formal plan to widen the route was delayed. On May 20, Deputy Prime Minister Ehud Olmert reportedly told U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell that the plan would not be carried out.163 Also on May 20, Attorney General Menachem Mazuz asked the IDF to revise the plan, arguing that it would not pass international or domestic legal tests.164 According to press reports, the IDF has since debated offering compensation to owners of demolished homes under such a plan.165 The IDF is also reportedly considering inviting Mazuz and Supreme Court Chief Justice Aharon Barak to tour the route to convince them of the need for further destruction.166 No decisions have been announced on the proposed plan.

IDF commanders on the ground have voiced their desire to wipe away rows of housing to reduce risks faced by their forces. “I’d eliminate at least another 200 meters of houses, leaving my soldiers outside anti-tank weapon range,” said Colonel Pinhas “Pinky” Zuaretz, in June 2004, while still head of Israeli forces in the southern Gaza Strip.167

According to Zuaretz’s replacement, Colonel Yehoshua Rynski, the IDF has recommended to the Defense Ministry that the buffer zone be widened to three hundred meters.168 Rynski appeared to be speaking of demolishing all homes within three hundred meters of the IDF wall – i.e., nearly four hundred meters from the border – since most of the Palestinian homes within three hundred meters of the border itself have already been destroyed and one of the purposes of the demolitions is to put greater distance between IDF positions and the camp.169 According to Rynski, the IDF has “grave suspicions”170 that Palestinian armed groups are smuggling rockets and surface-to-air missiles into Rafah that are far more sophisticated than the homemade rockets currently being used. So far, there is no evidence suggesting that such weapons have reached the Gaza Strip, and the IDF did not claim that this has happened; both Palestinian armed groups and the IDF have told Human Rights Watch that such weapons would have been used already had they arrived. Foreign diplomats with whom Human Rights Watch spoke have expressed skepticism about the likelihood of such weapons entering Rafah through Egypt in the foreseeable future.

In such a densely populated area, widening the buffer zone to this extent would affect hundreds, if not thousands, of Palestinian homes. Based on an analysis of satellite imagery, Human Rights Watch estimates that a buffer zone extending four hundred meters from the border would result in destroying approximately 30 percent of the central camp. This would result in the displacement of tens of thousands of Palestinian civilians, already living in one of the most densely populated areas on earth.

[150] Ariel Sharon and David Charnoff, Warrior: The Autobiography of Ariel Sharon, p. 258.

[151] First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions, Art. 52. Israel has not ratified the Additional Protocols but its provisions on indiscriminate warfare are widely considered customary norms of international law, binding on all parties to a conflict. The U.S. government, which has also not ratified the Protocols, stated in 1987 that it finds a number of Protocol I’s provisions to be customary. Among them are: limitations on the means and methods of warfare, especially those methods which cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering (art. 35); protection of the civilian population and individual citizens, as such, from being the object of acts or threats of violence, and from attacks that would clearly result in civilian casualties disproportionate to the expected military advantage (art. 51); protection of civilians from use as human shields (arts. 51 and 52); prohibition of the starvation of civilians as a method of warfare and allowing the delivery of impartial humanitarian aid necessary for the survival of the civilian population (arts. 54 and 70); taking into account military and humanitarian considerations in conducting military operations in order to minimize incidental death, injury, and damage to civilians and civilian objects, and providing advance warning to civilians unless circumstances do not permit (arts. 57-60). Michael J. Matheson, Remarks on the United States Position on the Relation of Customary International Law to the 1977 Protocols Additional to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, reprinted in “The Sixth Annual American Red-Cross Washington College of Law Conference on International Humanitarian Law: A Workshop on Customary International Law and the 1977 Protocols Additional to the 1949 Geneva Conventions,” American University Journal of International Law and Policy, vol. 2, no. 2, Fall 1987, pp. 419-27.

[152] “The presence within the civilian population of individuals who do not come within the definition of civilians does not deprive the population of its civilian character” (First Additional Protocol, Art. 50(3)).

[153] “Transcript of GOC Southern Command Regarding the Findings of the Investigation of the Demolition of the Buildings in Rafah (10-11.01.02),” IDF Spokesperson’s Unit, January 27, 2002. Almog declined an interview request from Human Rights Watch.

[154] “IDF demolitions at Rafah: UNRWA assistance to homeless refugees,” UNRWA press release, January 14, 2002; “More than 100 Palestinian families become homeless in Rafah after their houses were demolished,” PCHR press release, January 12, 1002; “Comprehensive data regarding Rafah house demolitions,” B’tselem press release, January 13, 2002.

[155] Amira Hass, Amos Harel, and Nathan Guttman, “IDF razes homes in retaliation,” Ha’aretz, January 11, 2002; Danny Rubinstein, Amos Harel, and Zvi Barel, “Palestinians present evidence they were home when bulldozers came to Rafah,” Ha’aretz, January 18, 2002.

[156] “Transcript of GOC Southern Command Regarding the Findings of the Investigation of the Demolition of the Buildings in Rafah (10-11.01.02),” IDF Spokesperson’s Unit, January 27, 2002.

[157] Fourth Geneva Convention, Art. 33.

[158] Quoted in Akiva Eldar, “Under cover of revenge,” Ha’aretz, January 15, 2002. Samiya was head of the southern command until 2000, directly preceding Almog. He declined an interview request from Human Rights Watch.

[159] Both Sharon and Mofaz previously headed the IDF Southern Command, from 1969-1972 and 1994-1996, respectively.

[160] “Palestinians: IDF razing homes in Gaza refugee camp,” Ha’aretz online, May 14, 2004.

[161] “Israeli army surrounds Gaza camp,” BBC Online, May 17, 2004, available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/3720121.stm.

[162] “Rafah: A Weapons Factory and Gateway,” IDF Spokesperson’s Unit, May 2004, p.13, available at: www1.idf.il/SIP_STORAGE/DOVER/files/5/31365.pdf.

[163] “Demolitions in Gaza to end: Israel tells U.S.,” Agence France-Presse, May 20, 2004.

[164] Ramit Plushnick-Masti, “Israeli army seeks to expand Gaza-Egypt border road by 300 meters requiring demolition of dozens of homes,” Associated Press, May 21, 2004.

[165] Ze’ev Schiff, “Israel proposes payment for homes razed to widen Philadelphi route,” Ha’aretz, May 23, 2004.

[166] Amos Harel, “IDF Mulls inviting AG, top jurists to tour Rafah,” Ha’aretz, August 13, 2004.

[167] Tsadok Yehezkeli, “Regards from Hell,” Yediot Ahronoth, June 11, 2004 (Hebrew). Colonel Zuaretz was wounded and lost a foot in a roadside bomb attack near Morag settlement, between Rafah and Khan Yunis, on July 8. Islamic Jihad claimed responsibility.

[168] Mark Heinrich, “Cat-and-Mouse Conflict Plays Out in Gaza Corridor,” Reuters, August 31, 2004.

[169] This was also the impression of the journalist who interviewed Rynski (Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Mark Heinrich, Reuters, September 21, 2004). In response to an inquiry from Human Rights Watch to clarify the remark, the IDF said that “The plan has not yet been finalized, nor approved. Therefore, it [sic] will be premature and inappropriate to go into detail at this [sic] piont” (Human Rights Watch email communication with IDF Spokesperson’s Unit, September 23, 2004).

[170] Steven Gutkin, “Israel Suspects Palestinian Militants on Missiles,” Associated Press, August 15, 2004.

| <<previous | index | next>> | October 2004 |