<<previous | index | next>>

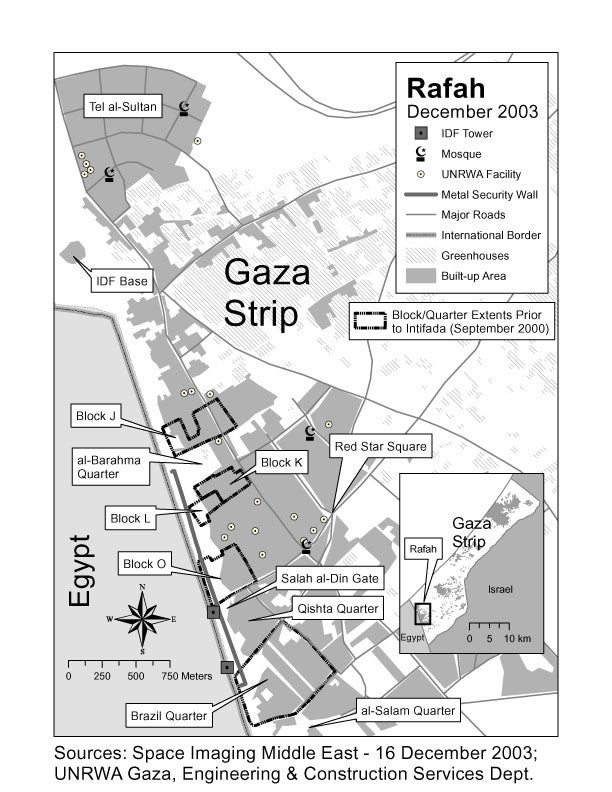

Map 2: Rafah Features

Rafah

Rafah is a remote and dusty city and refugee camp of sprawling concrete homes in the southernmost point of the Gaza Strip. According to the Rafah Municipality, the total population of the area is 145,000. Eighty-four percent of these people are refugees.62 Rafah is the poorest and one of the most devastated areas of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The movement of Rafah residents is often restricted with closure of the Abu Holi/Matahen checkpoints, which cut the city from the northern half of the Gaza strip, sometimes for days without explanation. The Mediterranean Sea is less than ten kilometers away, but access is blocked by the Gush Katif settlement bloc that runs along the coast, on top of Gaza’s best water sources.

Rafah has three overlapping areas. The town is the original part of Rafah that existed before 1948; many neighborhoods with family names (Qishta, Sha’er) are named for lands owned by original Rafah residents. The camp was established after 1948 to accommodate forty-one thousand refugees from what is now Israel, and is divided into alphabetical blocks (Block O, Block P, etc.). Finally, there are two Israeli-designed housing projects, Tel al-Sultan and Brazil.

During the first decades of the occupation, the Israeli government attempted to “thin out” the Gaza refugee camps by designing housing projects outside major camp areas. After the mass house demolitions throughout the Gaza camps in 1971 (see below), the Israeli government built a number of housing projects to “resettle”63 displaced persons, including two near Rafah: Brazil (to the south of the camp) and Canada (in what was then Israeli-occupied Sinai). Both were located on sites used by UN peacekeepers from those countries between 1956 and 1967. Under the terms of the 1979 Camp David peace treaty, the residents of Canada were to be repatriated to the Gaza Strip, though the process is yet to be completed twenty years later.64 A “new” Canada housing project was later built on the Gaza side of the border in an area called Tel al-Sultan.

The extended family is still the main social unit in Rafah, and is key to understanding housing patterns. As with other refugee camps in Gaza, population density is extremely high, with many people crowded into small living spaces. Extended families often own clusters of houses; typically, there is a small house from earlier days in the camp, often with nothing more than an asbestos roof. As sons start their own families, they build new homes nearby. In many cases, families build multi-story houses, with each son starting his own family on a different floor.

The border area with Egypt is known to Israelis as the “Philadelphi” corridor, named after the IDF designation for the patrol road that runs along the border. Because Rafah and the Sinai were ruled together from 1948 until 1982 (by Egypt from 1948 to 1967, by Israel in 1956 and from 1967 to 1982), the international border delineated by the Camp David peace treaty bisected the town between Egypt and the Gaza Strip, leaving families separated and houses within meters of the border.

The 1994 Gaza-Jericho agreement between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) delineated a Military Installation Area (or “pink zone,” referring to its color on the map appended to the agreement), approximately one hundred meters wide along the border, where the IDF has maintained direct authority.65 Israeli officials have at times argued that the IDF is not an Occupying Power in the Pink Zone, implying that they have more latitude to destroy property there. In explaining a major demolition operation in January 2002, for example, Major-General Doron Almog, head of the IDF Southern Command, told journalists:

In general, it is important to note that the Pink Area, as it was defined in the agreement, is not actualized and there are still Palestinian houses belonging to the refugee camp that are very close to the Philadelphi route which is also a completely Israeli security controlled area. … The area by definition is not an occupied area and Israel has the right to operate [there].66

The Oslo Accords, which set the framework for the Gaza-Jericho agreement, were transitional agreements that left the final status of the West Bank and Gaza open to further negotiations; as such, they did not change Israel’s status as the Occupying Power. The IDF does not have a freer hand to demolish Palestinian houses simply because they are inside the pink zone. Under international law the rights of protected persons cannot be affected by special agreements with local authorities as long as the territory remains occupied.67

Mass Demolition: Security Rationales, Demographic Subtexts

While Israel’s punitive and administrative house demolition policies have targeted individual homes, Israel has also in the past undertaken widespread destruction of neighborhoods, camps, and villages for putative security or military purposes. The apparent rationales for much of the destruction in Rafah since 2000 – namely, the need for “clear” borders and, to a lesser extent, to facilitate maneuverability of forces in densely populated areas – are not new. Such demolitions have also been linked to demographic changes.

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, the Haganah (the pre-state Zionist military) issued orders to clear all Arab villages within five kilometers of the Lebanese border after a local cease-fire had begun. As part of this policy, the Haganah depopulated and later destroyed a dozen border villages in the north in late 1948 and early 1949, pushing the inhabitants either across the border or to other areas of what became Israel. According to Israeli historian Benny Morris:

… the political desire to have as few Arabs as possible in the Jewish State and the need for empty villages to house new immigrants meshed with the strategic desire to achieve ‘Arab-clear’ frontiers and secure internal lines of communication. It was the IDF that set the policy in motion, with the civil and political authorities often giving approval after the fact.68

Between 1948 and 1950, Israeli forces ejected between thirty and forty thousand Palestinians beyond the boundaries of the state in various “border-clearing” operations and subsequent sweeps aimed at returnees.69

Unlike in 1948, population displacement and property destruction after the 1967 war was concentrated mostly in border areas: along the boundary that had separated the West Bank from Israel (known as the Green Line) and near the external borders of the West Bank. The IDF razed the villages of Beit Nuba, ‘Imwas, and Yalu, located near the strategic Latrun salient northwest of Jerusalem, in June 1967; later, a recreational area called “Canada Park” was built in their place. The same month, the IDF demolished the Green Line villages of Beit ‘Awa and Beit Marsam near Hebron.70 From June 9-18, the IDF destroyed 850 of the 2,000 dwellings71 in the town of Qalqiliya, located near the Green Line; only the intervention of a group of Israeli intellectuals saved the rest.72

Equally important to Israel was the Jordan Valley, on the external border of the West Bank. While up to a quarter of the population of the West Bank left after the war, the Jordan Valley’s population fell by eighty-eight percent, to 10,778. In subsequent years, the population grew to some twenty thousand.73 The bulk of those who fled across the river to Jordan were fifty thousand refugees living in three large camps in the valley – ‘Ein al-Sultan, Nu’aymah, and ‘Aqbat Jabir. According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, the IDF bulldozed the Jordan Valley communities of Jiftlik, Ajarish, and Nuseirat in late 1967.74 Israel’s first settlements in the OPT were also in the Jordan Valley, underlining the importance given by Israel to control over the external borders of occupied territories.

The IDF destoyed this Block J house, residents unknown, in May 2004.

(c) 2004 Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch

The Gaza Strip has been the major site of mass demolitions for the stated purpose of enhancing the mobility of military vehicles in urban areas; such security considerations also dovetailed with demographic ones. General Ariel Sharon, head of the IDF Southern Command after the 1967 war, believed the Palestinian refugee “problem” could be solved by reducing or eliminating the refugee camps.75 In November 1969, the IDF described to UNRWA plans “to improve the water and electricity supply and to widen roads in refugee camps, noting that some houses would have to be removed.” UNRWA demurred, citing the need for permission from the U.N. General Assembly.76

The IDF eventually went ahead without UNRWA’s cooperation. In the summer of 1971, the IDF destroyed approximately two thousand houses in the refugee camps of the Gaza Strip, including Rafah. Bulldozers plowed through dense urban areas to create wide patrol roads to facilitate the general mobility of Israeli forces; they were not connected to combat activities. The demolitions displaced nearly sixteen thousand people, a quarter of them in Rafah.77 At least two thousand of the displaced were moved to al-Arish, in the Sinai peninsula (then also under Israeli control), and several hundred were sent to the West Bank. Israeli officials reportedly argued that demolitions would serve both developmental and demographic aims:

The Israelis say that their program of demolishing houses and putting in patrol roads and lighting will begin by restoring security to the camps’ inhabitants. In the long run, they say, by reducing congestion and building new housing and other facilities, they will provide the beginnings of a decent life. Israeli officials are not yet prepared to discuss the long-range aspects. They say they are legally justified in moving refugees from Gaza into occupied Egyptian territory in the Sinai Peninsula.78

Some of those displaced in 1971 again lost their homes in May 2004. Human Rights Watch researchers spoke to a number of such families, many of whom identified the repeated bulldozing with Ariel Sharon personally. “We call him ‘the bulldozer,’” one man told a British journalist as he stood in the ruins of his home. “This is not the first time he’s done this to us. The first time was in 1971.”79 Human Rights Watch researchers also observed a collapsed building in Brazil near the border with the phrase “Sharon passed through here” [shāron marr min honā] scrawled on it in spray paint.

|

Box 1: A Bulldozer Driver’s View Property destruction to facilitate movement of military forces reappeared in the current uprising during the IDF assault on the Jenin refugee camp in April 2002. The IDF used D9 bulldozers to plow paths into the center of the camp after the killing of nine soldiers inside the camp. The IDF also razed most of the Hawashin district. According to an investigation by Human Rights Watch, the IDF completely destroyed 140 buildings in Jenin and rendered two hundred more uninhabitable. More than a quarter of the population became homeless. “While there is no doubt that Palestinian fighters in the Hawashin district had set up obstacles and risks to IDF soldiers,” Human Rights Watch found, “the wholesale leveling of the entire district extended well beyond any conceivable purpose of gaining access to fighters, and was vastly disproportionate to the military objectives pursued.”80 The following month, a D9 bulldozer driver who participated in much of the destruction spoke frankly with an Israeli journalist about his experiences: For three days, I just destroyed and destroyed. The whole area. Any house that they fired from came down. And to knock it down, I tore down some more. They were warned by loudspeaker to get out of the house before I [would] come, but I gave no one a chance. I didn’t wait. I didn’t give one blow, and [then] wait for them to come out. I would just ram the house with full power, to bring it down as fast as possible. I wanted to get to the other houses. To get as many as possible. Others may have restrained themselves, or so they say. Who are they kidding? Anyone who was there, and saw our soldiers in the houses, would understand they were in a death trap. I thought about saving them. I didn’t give a damn about the Palestinians, but I didn’t just ruin with no reason. It was all under orders. Many people where inside houses we st[arted] to demolish. They would come out of the houses we where working on. I didn’t see, with my own eyes, people dying under the blade of the D9 and I didn’t see house[s] falling down on live people. But if there were any, I wouldn’t care at all. I am sure people died inside these houses, but it was difficult to see, there was lots of dust everywhere, and we worked a lot at night. I found joy with every house that came down, because I knew they didn’t mind dying, but they cared for their homes. If you knocked down a house, you buried 40 or 50 people for generations. If I am sorry for anything, it is for not tearing the whole camp down. … As far as I am concerned, I left them with a football stadium, so they can play. This was our gift to the camp. Better than killing them. They will sit quietly. Jenin will not return to what it use[d] to be.81 After publication of the article in the newspaper Yediot Ahronoth, the IDF gave Nissim a citation for outstanding service. |

During the current uprising, property destruction in the Gaza Strip for the security of the IDF and settlers has far surpassed punitive demolitions. Most people inside the Gaza Strip who have lost their homes were not alleged to have any connection with those who participated in armed attacks. Rather, the IDF has seized property, razed land, and destroyed homes in the context of creating “buffer zones” for military bases, Israeli settlements, and the roads that serve them.

[62] Human Rights Watch interviews with Rafah Mayor E. Saied F. Zourob and Rafah City Manager Dr. Ali Shehada Ali Barhoum, Rafah, July 15, 2004.

[63] The housing projects were divided into parcels of land with ninety-nine-year leases. Families accepting them would have to renounce all claims to refugee status, cover construction and infrastructure costs themselves, and demolish their camp shelters (whose land would then be taken over by the IDF, exacerbating the housing crisis). The additional restrictions on land use in the projects and lack of government investment meant that qualify of life in the projects was not appreciably better than in the camps. “In summary, the government resettlement program was not a genuine effort to provide housing … but rather a political attempt to eradicate the refugee presence and the political responsibilities it carried” (Sara Roy, The Gaza Strip: The Political Economy of De-Development (Washington: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1995), p. 188; see also Simcha Bahiri, Construction and Housing in the West Bank and Gaza (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1989), p. 32).

[64] For stories on the plight of the residents of Canada, see Dick Doughty and Mohammed El Aydi, Gaza: A Legacy of Occupation: A Photographer’s Journey (West Hartford, CT: Kumarian Press, 1995).

[65] Agreement on the Gaza Strip and the Jericho Area, Annex I: Protocol Concerning Withdrawal of Israeli Military Forces and Security Arrangements, Art. 6 and Map No. 1.

[66] “Transcript of GOC Southern Command Regarding the Findings of the Investigation of the Demolition of the Buildings in Rafah (10-11.01.02),” IDF Spokesperson’s Unit, January 27, 2002.

[67] Fourth Geneva Convention, Arts. 7, 47.

[68] Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 505. The policy and practice of expulsions in the northern area are documented on subsequent pages. Morris supports the expulsions policies he has documented. In an interview with Ha’aretz, he proclaimed, “There is no justification for acts of rape. There is no justification for acts of massacre. Those are war crimes. But in certain conditions, expulsion is not a war crime. I don’t think that the expulsions of 1948 were war crimes. You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs. You have to dirty your hands.” (Ari Shavit, “Survival of the Fittest,” Ha’aretz, January 9, 2004).

[69] Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 536.

[70] Nur Masalha, The Politics of Denial: Israel and the Palestinian Refugee Problem (London: Pluto Press, 2003), p. 195-199

[71] Figures given by John Reddaway, Deputy Commissioner-General of UNRWA, in the Daily Star, June 21, 1967, cited in Politics of Denial, p. 215.

[72] Yossi Melman and Dan Raviv, “Expelling Palestinians; It Isn’t a New Idea, and It Isn’t Just Kahane’s,” Washington Post, February 7, 1988.

[73] William Harris, Taking Root: Israeli Settlement in the West Bank, the Golan, and Gaza-Sinai, 1967-1980 (New York: Research Studies Press, 1980), pp. 9-11.

[74] “The Middle East Activities of the International Committee of the Red Cross: June 1967-June 1970,” International Review of the Red Cross, September 1970, pp. 485-486.

[75] Ariel Sharon and David Charnoff, Warrior: The Autobiography of Ariel Sharon (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), p. 258.

[76] Benjamin Schiff, Refugees Unto the Third Generation: UN Aid to Palestinians (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1995), p. 196.

[77] See Martin van Creveld, The Sword and the Olive: A Critical History of the Israel Defense Force (New York: Public Affairs, 2002), p. 339; Sara Roy, The Gaza Strip, p. 105

[78] Richard Eder, “Gaza a Monument to Wretchedness Caused in Mideast,” New York Times, August 20, 1971.

[79] Chris McGreal, “‘They have no humanity. They didn't even give us two minutes to get out,’” Guardian, June 4, 2004.

[80] See Jenin: IDF Operations (Human Rights Watch, May 2002).

[81] Tsadok Yehezkeli, “‘I Made Them a Stadium in the Middle of the Camp,’” Yediot Ahronoth, May 31, 2002 (Hebrew), translation available at: http://www.gush-shalom.org/archives/kurdi_eng.html.

| <<previous | index | next>> | October 2004 |