Summary

Baha’is are the largest unrecognized religious minority in Iran. They have been the target of harsh, state-backed repression since their religion was established in the 19th century. After the 1979 revolution, Iranian authorities executed or forcibly disappeared hundreds of Baha’is, including their community leaders. Thousands more have lost their jobs and pensions or were forced to leave their homes or country.

For the past four decades, the authorities’ serial violations of Baha’is’ rights have continued, directed by the state’s most senior officials and the Islamic Republic’s ideology, which holds extreme animus against adherents of the Baha’i faith. While the intensity of violations against Baha’is has varied over time, the authorities’ persecution of people who are members of this faith community has remained constant, impacting virtually every aspect of Baha’is’ private and public lives.

In recent years, as Iranian authorities have brutally repressed widespread protests demanding fundamental political, economic, and social change in the country, the authorities have also targeted Baha’is. Authorities have raided Baha’i homes, arrested dozens of Baha’i citizens and community leaders, and confiscated property owned by Baha’is.

Iranian authorities have intentionally and severely deprived Baha’is of their fundamental rights. Authorities have denied Baha’is’ their rights to freedom of religion and political representation. They have arbitrarily arrested and prosecuted members of the Baha’i community due to their faith. Authorities routinely trample on Baha’is’ rights to education, employment, property, and dignified burial.

The Islamic Republic’s repression of Baha’is, particularly after 1979, is enshrined in Iranian law and is official government policy. The country’s repressive laws and policies are zealously enforced by the country’s notorious security forces and judicial authorities. Judicial authorities, for example, interpret Iran’s vaguely defined national security laws as classifying Baha’is as an outlawed religious minority community, and as an illegal group intent on disrupting national security.

Human Rights Watch believes that the cumulative impact of authorities’ decades-long systematic repression is an intentional and severe deprivation of Baha’is’ fundamental rights and amounts to the crime against humanity of persecution.

The Rome Statute, the founding treaty of the International Criminal Court (ICC), defines persecution as the intentional and severe deprivation of fundamental rights contrary to international law by reason of “the identity of the group or collectivity,” including on national, religious, or ethnic grounds. Under international law, crimes against humanity are some of the most serious crimes that are “committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack.”

In this report, Human Rights Watch analyzed Iranian authorities’ major violations of Baha’is’ fundamental rights and found them to be widespread and systematic practices carried out as a matter of state policy.

Iranian authorities often claim that Baha’is are prosecuted when they commit national security crimes such as “propaganda against the state,” but that Baha’is are otherwise free to enjoy their rights as citizens. Yet, Human Rights Watch found that the Iranian government prosecutions of Baha’is, including in recent years, have regularly targeted Baha’is for merely belonging to the Baha’i faith group or expressing their faith. Iranian court documents show that, in government prosecutions of Baha’i members, judicial authorities regularly refer to the Baha’i faith as a “deviant cult” and the religious community as an “illegal group.”

Further, discrimination against members of the Baha’i community is official state policy. Several state policy memorandums and government documents reviewed by Human Rights Watch, almost all of which remain in effect, stipulate that being a member of the Baha’i faith is qualifying grounds for exclusion from employment and educational opportunities in Iran, as well as justification for the state’s denial of pensions and confiscation of property.

Baha’is who spoke to Human Rights Watch described their persecution as a series of violations that begin with their first encounters with the Iranian state and impact every aspect of their lives, including education, employment, and marriage.

“[When I left Iran to continue my education], I did not intend to emigrate. But my experience at the university outside of the country was very different, as if for the first time a burden was lifted off my shoulder and the boot on my neck had disappeared… There [abroad] I experienced a strange freedom, and for the first time I was equal with other people, and no one was pulling themselves away from me,” said Negar Sabet, 38-year-old daughter of Mahvash Sabet Shahriari, a prominent member of the Baha’i community currently imprisoned in Iran.

The Iranian Supreme Revolutionary Cultural Council (ISRCC)’s confidential memorandum issued on February 25, 1991, is a foundational policy document for the government authorities’ systematic and widespread abuses against Baha’is that also reveals the state’s clear discriminatory intent in its actions against Baha’is. The memorandum, which has been repeatedly referenced in numerous Iranian court documents since its publication, lays out specific state policy objectives to expel Baha’is from jobs with influence and “block their progress and development” as a community by limiting their educational and economic opportunities. This document has been repeatedly referenced in subsequent government and judicial correspondence as a justification for denying Baha’is enrolment in universities in Iran.

Iranian authorities have used several additional policies and legal provisions to systematically deny Baha’is access to employment, pensions, and benefits in the public sector. The government also discriminates against Baha’is in the private sector by suspending business licenses and arbitrarily closing Baha’i-owned businesses. Collectively, these policies economically strangle the Baha’i community and have been coupled with government legal proceedings that have confiscated hundreds of properties belonging to individual Baha’is and the Baha’i community.

Iran is not a member of the ICC, and under the Rome Statute the crime of persecution can be prosecuted only in connection with other crimes. However, there is no such requirement under customary international law. The commission of crimes against humanity can also serve as the basis for individual criminal liability not only before domestic courts of the country where the crime was perpetrated, the ICC, and in international tribunals, but also in domestic courts outside the country in question under the principle of universal jurisdiction. Four decades after Iran’s leadership made the decision to systematically persecute the Baha’i community, UN member countries should urgently support all available accountability measures for these crimes including investigation and prosecution through domestic courts, in accordance with national laws. They should also renew the mandate of the UN Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Islamic Republic of Iran and ensure it has adequate resources to document the serious violations and international crimes against the Baha’is. Where possible, national judicial authorities should collect information related to the persecution of Baha’is as part of any future structural investigation into serious crimes in Iran.

Recommendations

To the Iranian Government

- Immediately revoke all policies and repeal laws that legalize violations of the rights of Baha’is, including but not limited to:

- Article 12 of the Iranian Constitution;

- The 1991 confidential memorandum issued by the Iranian Supreme Revolutionary Cultural Council (ISRCC);

- Section 34 of Article 8 of the 1993 law on administrative offenses;

- Repeal of articles 499 bis and 500 bis of the Penal Code that have criminalized freedom of thought and belief and are now used to convict Baha’is.

- Immediately cease persecution of Baha’is on the basis of their faith and release all those who are detained or who have been convicted on charges of membership in the Baha’i faith.

- Reform laws as well as the judicial and administrative processes to guarantee non-repetition of similar abuses and crimes.

- Publish all material, including government orders and confidential agreements related to government policies toward Baha’is, and disclose the fate of hundreds of those members of the Baha’i community who have been disappeared.

- Immediately grant access to Baha’is to employment and education at all levels on an equal basis to other Iranian nationals.

- Immediately restore old age and veterans’ pensions to eligible Baha’is.

- Cease confiscation of properties owned by Baha’is on the basis of their faith and ensure fair and transparent judicial process for property disputes.

- Cooperate with and heed the recommendations of UN bodies and human rights mechanisms.

- Ratify the Rome Statute and incorporate crimes against humanity, including the crime of persecution, into national criminal law with a view to investigating and prosecuting individuals credibly implicated in these crimes.

To the United Nations Independent, International Fact-Finding Mission

- As part of establishing the facts and circumstances surrounding the alleged violations related to the protests that began in Iran in September 2022, collect information related to any crimes committed against Baha’is as it relates to hate speech, which increased after the protests, and the increase in the targeting of Baha’i women.

To All States

- Issue individual and collective public statements expressing concern about Iranian authorities' commission of the crimes of persecution against Baha’is.

- Incorporate the crimes against humanity of persecution into national criminal law with a view to investigate and prosecute individuals credibly implicated in these crimes.

- Where possible and in accordance with domestic laws, support national judicial authorities collecting information related to the persecution of Baha’is as part of any future structural investigation into serious crimes in Iran.

- All states and the UN Human Rights Council should ensure the renewal of the mandates of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran and the UN Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Islamic Republic of Iran mandates at the upcoming 55th session of the Human Rights Council.

- Support any national investigation and prosecution of those credibly implicated in serious crimes committed in Iran against the Baha’is, under the principle of universal jurisdiction and in accordance with national laws.

- Impose targeted sanctions, including asset freezes, against officials and entities credibly implicated in the continued commission of grave international crimes, including persecution.

- All states should recognize as a persecuted minority members of the Baha’i community who are or were nationals of the Islamic Republic of Iran because they share common characteristics that target them for religious persecution as being presumptively eligible for refugee status for purposes of resettlement or asylum.

Methodology

The Iranian government does not allow international human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch to enter the country to conduct independent investigations into human rights abuses. Iranian activists, journalists, human rights lawyers, relatives of political prisoners, and former political prisoners are often not comfortable carrying out extended conversations on human rights issues via telephone or email, fearing government surveillance. The government often accuses its critics inside Iran, including human rights activists and Baha’is, of being agents of foreign states or entities, and prosecutes them under Iran’s national security laws.

This report is based on years of documentation carried out by Human Rights Watch, as well as Iranian human rights groups, of Iranian authorities’ violations against Baha’is in Iran. Human Rights Watch researchers reviewed dozens of government policies, as well as court documents and government correspondence with Baha’is. Most of these documents were accessed on the “Archive of the Persecution of Baha’is in Iran,” a website managed by the Bahá’í International Community (BIC), which represents the worldwide Baha’i community. Human Rights Watch reviewed additional documents collected by the Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA), an independent human rights documentation organization, and documents that Baha’is shared with Human Rights Watch during interviews.

Between May 2022 and March 2023, a Human Rights Watch researcher interviewed 14 Baha’is, some of whom lived in Iran and others who were based outside the country. The interviews were conducted remotely and in Persian.

Human Rights Watch also wrote to Iranian authorities for comment on these findings on January 23 and 25, 2024. At time of writing, Human Rights Watch did not receive a response.

I. State Policy Against Baha’is

According to the Bahá’í International Community (BIC), an international non-governmental organization representing the members of the Baha’i faith at the United Nations and regional bodies such as the European Union, the African Union, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Baha’is are the largest non-Muslim religious minority in Iran, estimated to be around 350,000 people at the time of the Iranian revolution in 1979.[1] The Baha’i religion was established in Iran in the 19th century. Since its establishment, Baha’is have faced persecution directed at members of the community by elements within the Iranian government and influential Shia clerics.[2] In the words of a prominent Iranian historian, Shia religious authorities have often directed “animosity” toward Baha’is due not only to doctrinal disagreements but also a fear of “Baha’i infiltration of government and society…”[3]. Central to the Iranian government’s theological opposition to Baha’is is that the Baha’i faith is a religion that came after Islam. Unfounded accusations continued to be levied against them even though Baha’i teachings prevent Baha’is from involvement in partisan politics and interference in politics and political matters. Baha’is continue to be discriminated against elsewhere in the region, including in Qatar, Egypt, and Yemen.[4]

After the 1979 Islamic revolution, the Iranian government made it official policy to discriminate against the Baha’is, including a state-sponsored campaign of persecution against the Baha’is.[5] Iranian state violence against the Baha’i community in the early years after the revolution was particularly harsh; BIC estimates that authorities executed or forcibly disappeared over 200 people who were Baha’i, including influential members of the community or those who served on Baha’i institutions. Thousands more were arrested, expelled from their jobs, or forced to leave the country.[6] While other unrecognized religious minorities in Iran, including Yarsanis (Ahl-e Haqq) who live mostly in Kurdish areas of Iran and Iraq, also face discriminatory restrictions, Iranian authorities have often singled out Baha’is as a target for repressive policies.[7]

Not only are Baha’is unrecognized as a religious minority in the Iranian constitution, resulting in serious rights violations, over the past four decades, Iranian authorities have institutionalized violations of Baha’i rights, including by adopting various policy measures and decrees that restrict, impede or block Baha’is from exercising their fundamental rights.

In 1983, Iranian authorities banned all Baha’i administrative and community activities, effectively criminalizing membership in the Baha’i faith group. On August 29, 1983, a revolutionary chief prosecutor, Seyyed Hussein Musavi-Tabrizi, announced a legal ban on all administrative and community activities undertaken by the Baha’i community. The 1983 order required dissolution of the national spiritual assembly, which was responsible for the management of Baha’i administrative affairs at the national level, such as marriages and burials, and the order also dissolved about 400 local-level Baha’i administrative bodies.[8]

The 1983 ban remains in effect. On February 16, 2009, in a letter to the Minister of Intelligence, Gholamhossein Ejeyi, Ghorbanali Dorri Najafabadi, then-prosecutor general, reiterated the 1983 ban. He said that “the activities of the perverse Baha’i sect on any level are illegal and banned, and their ties to Israel and opposition to Islam and the Islamic regime are established beyond doubt. The danger they pose to national security is supported with evidence and proven; thus, necessary measures will be taken against any substitute administration [set up by the Baha’is] that adheres to the same principles.”[9]

Following the initial brutal killing and executions of Baha’is in the early years after the revolution and with growing international pressure on Iran, in 1991, the Iranian Supreme Revolutionary Cultural Council (ISRCC) issued a confidential memorandum that directed authorities to focus on socioeconomically and politically oppressing Baha’is. The memorandum clearly established Iranian government policy to discriminate and deny the fundamental rights of the Baha’i community. The ISRCC, established in the early 1980s, is a state body charged with setting the state’s cultural agenda, particularly at the university level. It is headed by Iran’s president and its decisions can only be overruled by Iran’s supreme leader. The ISRCC memorandum that lays out government policy to discriminate against the Baha’i community, with a motive to dominate, was issued at the request of the supreme leader on February 25, 1991. The Iranian authorities have never denied the existence of this policy and several subsequent government correspondences have referred to the ISRCC to justify existing restrictions.

The 1991 ISRCC memorandum lays out the foundation of the abusive framework that Iranian authorities have used to persecute Baha’is for decades. According to the memorandum, the government must “block the progress and development of the Baha’i community”, outlining a series of provisions by which to do this, including expulsion from universities and public places of employment, enlisting their children in school with a “strong religious ideology” and destroying their cultural roots outside of Iran. The document also claims that Baha’is should not be expelled from the country, arrested imprisoned, or penalized “without reason.” In practice, however, Iranian authorities have arrested and penalized thousands of Baha’is citing their membership in the Baha’i Faith as the charge for the sentences against them.

A copy of this “secret” policy summary memorandum was first released in 1993 by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Islamic Republic of Iran and later published by BIC:

SUMMARY OF THE RESULTS OF THE DISCUSSIONS AND RECOMMENDATION

A. General status of the Baha’is within the country’s system

1. They will not be expelled from the country without reason.

2. They will not be arrested, imprisoned, or penalized without reason.

3. The government’s dealings with them must be in such a way that their progress and development are blocked.

B. Educational and cultural status

1. They can be enrolled in schools provided they have not identified themselves as Baha’is.

2. Preferably, they should be enrolled in schools which have a strong and imposing religious ideology.

3. They must be expelled from universities, either in the admission process or during the course of their studies, once it becomes known that they are Baha’is.

4. Their political (espionage) activities must be dealt with according to appropriate government laws and policies, and their religious and propaganda activities should be answered by giving them religious and cultural responses, as well as propaganda.

5. Propaganda institutions (such as the Islamic Propaganda Organization) must establish an independent section to counter the propaganda and brreligious activities of the Baha’is.

6. A plan must be devised to confront and destroy their cultural roots outside the country.

C. Legal and social status

1. Permit them a modest livelihood as is available to the general population.

2. To the extent that it does not encourage them to be Baha’is, it is permissible to provide them the means for ordinary living in accordance with the general rights given to every Iranian citizen, such as ration booklets, passports, burial certificates, work permits, etc.

3. Deny them employment if they identify themselves as Baha’is.

4. Deny them any position of influence, such as in the educational sector, etc.[10]

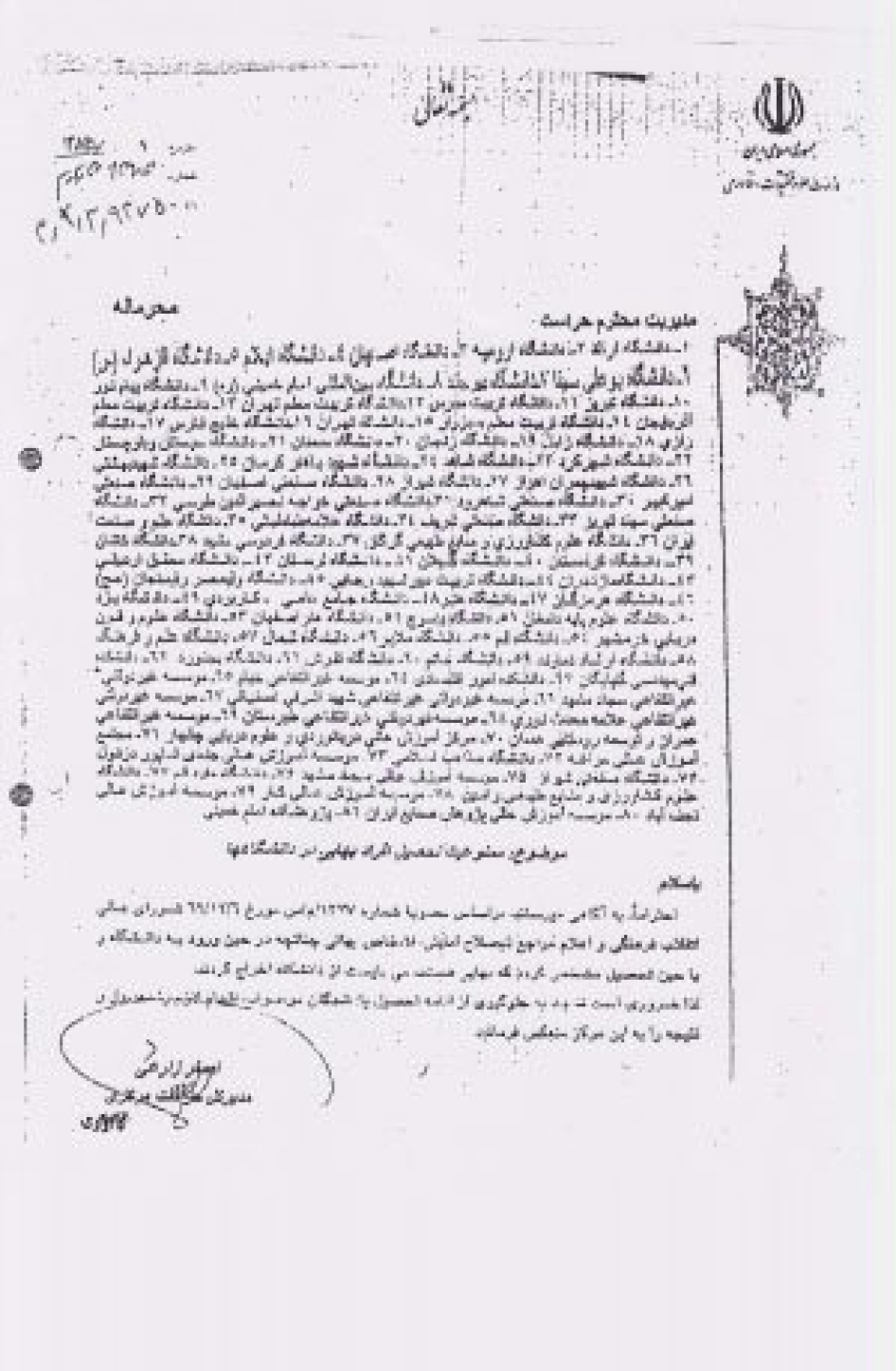

The 1991 ISRCC memorandum has been referred to in subsequent government correspondence, including a 2006 order of the Director General of the Central Security Office at the Ministry of Science and Research and Technology to bar Baha’i students from university education and a 2018 ruling of Branch 40 of the Court of Administrative Justice affirming this discriminatory policy in university education.

The severe restrictions laid out in the 1983 ban and the 1991 ISRCC memorandum are part of the comprehensive state policy that seeks to confine and control the lives of Baha’is in Iran today.

In 2006, BIC published a copy of a secret letter, dated October 29, 2005, and signed by the chairman of command headquarters of the Iranian armed forces, to intelligence agencies, the judiciary and police commanders, asking them to “identify all the individuals” belonging to the Baha’i faith in Iran.[11] According to BIC, this identification could be used for the purpose of monitoring them and expelling them from school, universities, and places of work.

II. Widespread and Systematic Violations of Baha’is’ Fundamental Rights

While the intensity of Iranian authorities’ repression of Baha’is has varied over the past 40 years, the fundamental rights violations have remained the same, impacting virtually every aspect of Baha’is’ private and public lives.

Denial of Religious Freedoms

As a religious minority unrecognized in Iran’s constitution, Baha’is are prohibited from establishing any official institutions, cannot freely hold prayers, even in private, or perform other acts that are integral to their religion, such as disseminating religious material.

The Iranian authorities have prosecuted members of the Baha’i faith on the basis of activities recognized under international human rights law as an integral part of religious freedom, such as distribution of religious materials, holding private prayer sessions, or speaking to non-Baha’is about their faith. For instance, in a May 2011 verdict issued by the revolutionary court of Amol in Mazandaran province, the judge determined that participating in Baha’i ziafats (community gatherings and prayers) was evidence of “propaganda against the state,” referring to the prosecutor general’s statement in 2008 that the Baha’i institutions are outlawed.[12]

State-Backed Incitement to Hatred

Not only have Baha’is been denied their right to practice their religion, they also have been the target of periodic state-backed incitement to hatred campaigns. For instance, in April 1955, a Shia preacher named Mohammad Taqi Falsafi, backed by other prominent Shia clergy, “began an orchestrated anti-Baha’i campaign” that demonized Baha’is, accused them of betraying the Iranian nation, and even called for their “banishment” from the country. The campaign spread across a number of cities, leading to mob violence and the killing of Baha’is, as well as attacks on Baha’i holy sites over roughly a month (the campaign began around the start of Ramadan and ended after the holy month).[13]

After the 1979 revolution, the speech of government officials, state institutions, government media outlets, and the Shia clerical establishment (which is closely intertwined with the post-1979 Iranian state) has consistently propagated incitement to hatred against the Baha’i community in Iran.

In post-revolutionary Iran, the supreme leader is the highest state power. Both Ayatollah Khomeini and Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the former and current supreme leaders respectively, issued fatwas (religious decrees) declaring that Baha’is are “spies,” “infidels,” and “unclean” and should be avoided.[14] According to the official website of Ayatollah Khamenei, in response to questions about interacting with Baha’i students and using food brought to someone’s home by Baha’is, Ayatollah Khamenei tells his followers that “all followers of the misguided Baha’i sect are unclean,” and “socializing with them should be avoided.”[15]

Six people who spoke to Human Rights Watch described being subjected to hateful comments during their primary education, particularly in religious studies classes. One Baha’i woman told Human Rights Watch:

I was in fourth grade when I entered the [Muslim] prayer hall with my friends. After the prayers were finished, teacher told all students loudly that the prayers won’t be accepted by God because there was an unclean person in the crowd. . .[16]

Another Baha’i woman, now 36-years-old, told Human Rights Watch:

I was in fourth or fifth grade, when the teacher was asking everyone about their religion. I comfortably responded that I am Baha’i and the teacher said Baha’is are not good people and are bad; that I should do my research when I get older and change my religion and do not tell my parents about it...[17]

Websites and figures affiliated with Iranian state entities also frequently publish propaganda material accusing, without evidence, Baha’is of espionage for Israel.[18] State-funded cultural and academic entities also hold workshops promoting hateful content against the Baha’is.[19] Over the past five years, Bahá’í International Community (BIC) has reported an increase in state-sponsored anti-Baha’i hateful material, particularly online through social media.[20] According to BIC, during the first four months of 2021, there was a 44 percent increase compared to the previous year in the number of hateful articles and other media products published or broadcast against the Baha’i community and faith by state-sponsored outlets or accounts. According to BIC, the number of individual items of hate propaganda released by these outlets monitored during 2022 exceeded ten thousand. One such recent social media campaign in July 2023 under the hashtag #Amir_Kabir_Thankyou ( #امیر_کبیر_متشکریم ) praised the mistreatment and executions of the early Baha’is during the Qajar dynasty and directly incited violence and encouraged the present day killing of Baha’is.

Arbitrary Arrests and Prosecution for Membership in the Baha’i Community

For decades, the Iranian authorities have used abusive national security provisions in Iran’s Islamic Penal Code to crack down on dissent and peaceful activism across Iran. Human rights defenders, lawyers, journalists, political opposition activists, and many others have all been targeted and imprisoned on the pretext of national security. The authorities have also vigorously used these vaguely defined national security provisions to prosecute Baha’is based solely on their faith identity.

Intelligence and judicial authorities regularly raid Baha’is’ homes, confiscate their belongings and arrest or summon them to judicial and intelligence bodies for questioning.[21] They commonly accuse and convict Baha’is on charges that include “assembly and collusion to act against national security” (article 620 of Islamic Penal Code), “membership in/establishing a group against the state [Baha’ism]” (articles 498 and 499 of Islamic Penal Code, sometimes also written as “membership in deviant cult”), and “propaganda against the state” (article 500 of Islamic Penal Code). Iranian court documents cite Baha’i group prayers, community gatherings, and creating kindergartens or youth classes as “evidence” for these charges.

Several court documents reviewed by Human Rights Watch show that Iranian courts have convicted people simply based on their Baha’i faith. When doing so, courts have accepted “evidence” of a person’s membership in an “illegal” group based on the defendant’s Baha’i faith and engagement in protected activities such as participation in prayer sessions or study groups. In a revolutionary court in Semnan, for example, in a verdict reviewed by Human Rights Watch, the court referenced activities such as being a teacher in Baha’i afterschool programs and being a member in an illegal group of the “Baha’i sect” as evidence of a criminal offense.[22]

In a verdict issued on July 13, 2021, Branch 2 of Yazd’s revolutionary court sentenced four Baha’i citizens to three years and four months in prison on the charges of membership in groups opposed to the state and propaganda against the state. The court based the sentence on the defendants' membership in an illegal group, using their statements of “being a Baha’i,” “participating in meeting for prayers,” and, for one of the defendants, their willingness to “help anyone who wants to become a Baha’i.”[23]

Over the past years, a few judges have ruled that “merely proselytizing for the Baha’i faith cannot be considered propaganda against the state and, fundamentally, the law does not criminalize the belief in the Baha’i faith to justify prosecuting and punishing individuals with such a charge.”[24] Such opinions, however, have been rare. They are overshadowed by the escalation of arrests and targeting of Baha’is by intelligence agencies, and by the continued conviction and sentencing of Baha’is based solely on their religious beliefs by other judicial authorities.

Iranian authorities also regularly accuse Baha’is of conducting espionage for Israel, without providing evidence. State propaganda materials and government statements often simply refer to Baha’is’ communication with the Universal House of Justice, a nine-member supreme ruling body of the Baha’i faith that has been located in the city of Haifa, Israel, for sixty years.[25]

During the summer of 2022 alone, authorities raided dozens of Baha’i homes and arrested at least 30 people, among them Fariba Kamalabadi and Mahvash Sabet, two prominent members of the Baha’i community both of whom previously spent 10 years in prison.[26] On May 22, 2022, in an oral statement delivered to the UN Human Rights Council, Simin Fahandej, a BIC representative said, “More than 1,000 Baha’is in Iran are in “limbo” between their initial arrests, their legal hearings and their final summons to prison.[27]

In 2008, authorities arrested seven members of the ad hoc national coordinating body for Baha’i community, known as the Yaran, that was established after the dissolution of the spiritual assemblies. The Yaran took care of the administrative, spiritual, and social needs of the Baha’i community in Iran such as marriages and burials. In a grossly unjust process, a revolutionary court sentenced these seven people to 20 years in prison on charges that included espionage, propaganda against the Islamic Republic, and the establishment of an illegal administration.[28] An appellate court subsequently reduced their sentences to 10 years in prison, which they served in full. Following their arrest, on February 16, 2009, Fars News Agency, which is close to Iran’s intelligence services, reported that Ayatollah Ghorbanali Dorri-Najafabadi, the public prosecutor-general at the time, declared that all activities of the “perverse Baha’i sect” are illegal and banned them in a letter he addressed to Gholam Hosein Mohseni-Ejehi, then-minister of intelligence.[29]

More recently, on July 31, 2022, Iranian authorities arrested 13 members of the Baha’i community, including Kamalabadi and Sabet, the two prominent members they had previously arrested in 2008. The Ministry of Intelligence issued a statement justifying the arrests by accusing the Baha’is of belonging to an “espionage party” that is spying for Israel. The statement added that those arrested were “propagating the teachings of fabricated Baha'i colonialism and infiltrating educational environments, particularly kindergartens.”[30] The statement was followed by a two-minute segment aired by the Islamic Republic Broadcasting Agency accusing Baha’is of promoting their religious material in kindergartens.[31] Human Rights Watch is aware of no evidence supporting this allegation.

On December 11, 2023, BIC reported that Branch 26 of Tehran’s revolutionary court sentenced Kamalabadi and Sabet to an additional 10 years in prison. Kamalabadi and Sabet remain detained in Evin prison. The two women were sentenced based on the charge of managing an (illegal) group of a deviant cult with the intention to act against national security.[32] According to BIC, Judge Iman Afshari, of Branch 26, rebuked the two women for “not having learned their lesson” from their previous imprisonment. On August 10, 2023, the Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA) reported that the court of appeal upheld the 10 year prison sentence against the two women.[33]

On August 13, BIC reported that the authorities rearrested 11 Baha’i citizens, including Jamaluddin Khanjani, a 90-year-old former Baha’i community leader who also had served 10 years in prison, as well as his daughter, Maria Khanjani and transferred them to Evin prison in Tehran.[34]

The practice of arbitrary prosecution of Baha’is dates to the very early days after the 1979 revolution when the Baha’i community estimates that 200 members, including members of local Baha’i governing boards, were executed or disappeared by the authorities during the initial years following the 1979 revolution. According to a statement issued by the Universal House of Justice, which is the nine-person body ruling body of the Baha’i faith, Iranian authorities executed eight members of the national spiritual assembly, the national governing body of Baha’i faith in Iran, on December 27, 1981, following a trial that fell grossly short of international standards.

Other members of the former leadership council, who were disappeared in August 1980, were feared dead, according to the same Universal House of Justice statement.[35] Shahin Sadeghzadeh Milani, son of Kambiz Sadeghzadeh Milani, one of the disappeared members of the former leadership council, told Radio Farda on August 31, 2021, that despite asking several high-level authorities about his father’s disappearance, his family had never received a response.[36]

Recent Penal Codes Additions Add Further Risks to Baha’is

In February 2021, President Hassan Rouhani signed into law two additional articles—articles 499 bis and 500 bis – to Iran’s penal code that could be used to prosecute unrecognized religious minorities, including Baha’is. Under the added article 499 bis, “anyone who insults Iranian ethnicities or divine religions, or Islamic schools of thought recognized under the constitution with the intent to cause violence or tension in society or with knowledge that such [consequences] will follow” will be subjected to imprisonment or financial fine.[37] Under the added article 500 bis, “anyone who as part of a cult, group, crowd or association and uses mind control methods and psychological inductions in real or virtual space,” or commits “any deviant educational or proselytizing activity that contradicts or interferes with the sacred law of Islam” including “making false claims or lying in religious and Islamic spheres, such as claiming divinity,” will be sentenced to two to five years of imprisonment or financial fines.[38]

In a context where authorities consider Baha’i beliefs as contrary to Islamic principles, these newly added, vague penal provisions provide a further basis for Iranian authorities to arrest and prosecute Baha’i for the expression of their beliefs.[39] Since entering into force, authorities have routinely used the new articles in tens of cases against members of the Baha’i community, as well as three Christians from Muslim background, who were in Rasht, Gilan Province.[40] On May 13, 2023, the Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA) reported that Branch One of Isfahan’s Revolutionary Court sentenced Enayatollah Naeemi, a Baha’i, to 15 years in prison. The conviction was based on charges that included a violation of article 500 bis, for Naeemi’s role in “establishing the Baha’i network of Yaran-e-Iran and Baha'I connections to Israel.”[41]

Denial of Access to Education

Under article 30 of the Iranian constitution, “The Government is bound to make available, free of charge, educational facilities for all up to the close of the secondary stage, and to expand free facilities for higher education up to the limits of the country's own capacity.”[42]

In the early years after the 1979 revolution, many Baha’i students were expelled from school. Since that time, members of the Baha’i community have been regularly denied access to education, particularly tertiary education.

Baha’i students continue to report being expelled from schools for simply being Baha’i and often for speaking out in support of their faith when teachers make offensive statements against their religion. School textbooks and education in school include incendiary content against the Baha’i faith, and if Baha’i students speak against the content, they can be expelled from school at any level, including primary, junior high, or high school.

On November 9, 2019, the Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA) reported that authorities at al-Zahra girls high school in Sari expelled a student after responding to her religious teacher’s offensive comments about Baha’is.[43] On July 12, 2020, a Baha’i father told the Center for Human Rights in Iran that his 15-year-old son was expelled from the Salam Alborz high school for being a Baha’i.[44] On September 11, 2019, Mohsen Haji Mirzai, the Minister of Education at the time told reporters that “if a student declares that he or she is a follower of an unrecognized religion and that act is considered proselytizing, their education is prohibited.”[45]

BIC has recorded over 100 instances on their website in which students were either denied access to education or subjected to unfair treatment in the classroom solely due to their religion.[46]

The ban on Baha’i students attending university that was laid out in the 1991 memo remains in effect. Iranian authorities continue to systematically prevent students who identify as Baha’i from registering at universities. Even if the Baha’i students are not identified during the entrance exam needed for acceptance in public universities, authorities expel them, in accordance with the 1991 memo, if the students reveal their faith.

The denial of access to university education has a profound impact on the ability of Baha’i youth to choose a profession and develop intellectually. A 36-year-old Baha’i woman told Human Rights Watch that in high school she had no motivation to study because she knew that no matter how hard she tried she would not be able to enroll in university.

The most common official pretext for excluding Baha’is from registering at universities is that their documents are incomplete. Human Rights Watch reviewed three letters in which university authorities provided further information. In two, authorities wrote that they could not verify the “general qualification” of the candidate. This unfounded pretext refers to the fact that the criteria for entering universities in Iran is belonging to one of the recognized religions in the Iranian Constitution - Christianity, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism. In one document reviewed by Human Rights Watch, they wrote that the enrollment was terminated because of the student’s “belief.”

Admitted students are required to declare their religion in the general qualification form for enrolling in universities. According to BIC, university administrators have told Baha’is that they are forced to use the phrase “unqualified” in order not to create documentation for the reasons behind the dismissals. Numerous court documents on the Archives of Baha’i Persecution website refer to the 1991 memo for non-admissibility of Baha’i students to university.

The Baha’i community has long tried to challenge this ban through legal and procedural avenues.

Prior to 2003, when registering for the national entrance exam, which is required for students seeking to enroll in public university, applicants were required to choose from one of the recognized religions: Islam, Christianity, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism. Applicants who indicated they belonged to a faith other than one of the four officially recognized religions in Iran were simply excluded from the exam.

The Baha’i library website has published correspondence between the “committee to oversee the implementation of the constitution” established by President Mohammad Khatami (1997 to 2005) and Khatami’s office after several Baha’i people raised the issue with his office. In this correspondence, the head of the committee recommended that the 1991 ISRCC memorandum’s position on denial of university education to Baha’is should be reviewed.[47]

According to BIC, in 2003, in response to international pressure, the government announced that it would drop the requirement that students declare their religious affiliation on the application for the national university entrance examination and that applicants would now be able to choose the religious studies subject they want to be tested on during the exam.[48] However, as HRANA continues to document, every year, the applications of Baha’is who register and participate in the exam are regularly marked as lacking essential documents or not meeting general qualifications which has the effect of continuing to prevent Baha’i students from registering at university.

The 1991 ISRCC confidential memorandum has remained the core policy guidance on preventing Baha’is’ enrollment in universities. According to a letter published on the BIC website, in 2006, the director general of the Central Security Office at the Ministry of Science and Research and Technology ordered the security offices of 81 public universities to expel Baha’i students in accordance with the memorandum. [49]

Baha’i students’ efforts to challenge this policy in court have been rejected numerous times by judicial bodies. In 2018, Branch 40 of the Court of Administrative Justice rejected a complaint filed by a Baha’i student who said that after being accepted in a university he was prevented from registering and choosing courses on the basis of his “religious minority” status.

The court ruled that the actions were taken in accordance with the 1991 ISRCC memorandum and therefore, legal.[50] On June 10, 2019, Branch 16 of the administrative justice court of appeal upheld the verdict.[51]

A 31-year-old woman expelled from a public university in Tehran in 2015 after receiving a Ministry of Science letter claiming they had not been able to verify her general qualifications told Human Rights Watch that after meeting with Morteza Nourbakhsh, the head of the Science Ministry screening (Gozinesh) office, for over three hours, he asked her to write a letter of complaint but promptly proceeded to “throw the letter in the trash can.”[52]

According to Human Rights News Agency (HRANA) and BIC, during the academic year 2022-2023, at least 64 Baha’i students were not able to get the national entrance exam’s test results from the official website.[53]

|

Year |

2022-2023 |

2021-2022 |

2020-2021 |

2019-2020 |

2018-2019 |

|

Number of Baha’i Students Denied Registration at Universities |

64 |

20 |

24 |

75 |

112 |

On various occasions Iranian authorities have cracked down against Baha’i community-led efforts to offer university level education to its members. In the last wave, in 2011, authorities raided the homes of more than 30 people who were instructors of the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education (BIHE), an educational entity established by the Baha’i community, and prosecuted them for their role in providing education to Baha’i students.[54]

According to notes taken by the lawyer of one of the BIHE trainers and reviewed by Human Rights Watch, authorities charged the BIHE trainer with “membership in the illegal deviant Baha’i sect with the intention to act against national security” through her “activities in the illegal Baha’i education center.”[55]

Denial of Baha’is’ Right to Work and Closure of Businesses

Baha’is are banned from most public sector jobs; Iranian authorities only allow Muslims or recognized religious minorities to serve in most public sector jobs. The government enforces this ban by requiring applicants to fill out forms about their religious background. During the first decade after the revolution, hundreds of Baha’is were dismissed from public sector jobs across the country and their pensions and retirement benefits were terminated.[56]

Under articles 19 and 29 of the Law on Restructuring the Human Resources of Government and Government-affiliated Ministries and Institutions of 1981, which remains in effect, “membership in the deviant sect [referring to Baha’is] that is recognized by consensus of Muslims to be outside Islam” is defined as an offense that results in permanent dismissal from civil servant jobs.[57] Similarly, under section 34 of article 8 of the 1993 Law on Administrative Offenses, which also remains in effect and applies to public sector employment, “membership in the deviant sect that is rejected by Islam” is defined as an offense that results in termination of employment.

Human Rights Watch reviewed two legal opinions by Iran’s Court of Administrative Justice that upheld this blatant employment discrimination against Baha’is. Iran’s Court of Administrative Justice under the supervision of the head of the judiciary, hears complaints against government officials and public institutions. In two legal opinions issued on April 29, 2007, and July 31, 2016, the court upheld the State Social Security Organization in Tehran’s decision to not allocate pension and benefits to two Baha’is who were dismissed from public sector jobs, citing the two discriminatory laws referenced above.[58] The 2007 ruling in upholding the government body‘s decision to refuse pension and other benefits to Baha’is dismissed from their positions, also referenced article 14 of Iran’s 1946 National Employment Law, which allows for permanent dismissal in cases where employees “lack reputation because of moral corruption.”

Iranian authorities’ widespread and systematic violations against Baha’is’ right to employment extends beyond the public sector. During the presidency of Mohammad Khatami from 1997 to 2005, correspondence between the president-appointed “Committee to Oversee the Implementation of the Constitution” and President Khatami’s office discussed complaints submitted by Baha’is that were dismissed from their jobs or denied professional licenses, such as a license to practice veterinary medicine. In this correspondence, in 2002, the committee head, Hossein Mehrpur, noted that existing government policy had established that “belief in one of the official religions of the country” is a condition for receiving a professional license such as a veterinary license. Therefore, according to Mehrpur, “a Baha’i veterinarian who applies for a license to engage in work is deprived of getting a license due to being a Baha’i.” This ban on Baha’i workers similarly extended to “any type of employment in a governmental or semi-governmental department, even on a contractual or daily wage basis,” Mehrpur explained in the correspondence.[59]

The discrimination against Baha’is extends further. Three Baha’i women told Human Rights Watch that employers in the private sector were put under pressure to fire them from their jobs. Others shared memories of their parents being dismissed from employment in the early decades after the revolution.

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that Iranian authorities also revoked or suspended licenses of private businesses owned by Baha’is, especially for “manifestation” of their religion, such as observing Baha’i holidays. BIC has published a copy of a letter dated April 9, 2007, from the Public Intelligence and Security Force, Tehran — Public Places Supervision Office to police commanders in Tehran that specifically stated:

Baha’i activities in high-earning businesses should be halted, and only those work permits that would provide them with an ordinary livelihood should be allowed…

Issuing of [work] permits for the activities of the mentioned individuals in sensitive business categories (culture, propaganda, commerce, the press, jewelry and watchmaking, coffee shops, engraving, the tourist industry, car rentals, publishing, hostel and hotel management, tailoring training institutes, photography and film, [illegible] Internet, computer sales and Internet cafés), should be prevented…

In accordance with the religious canons, work permits will not be issued to the followers of the perverse Baha’i sect in business categories related to Tahárat [cleanliness] (1. catering at reception halls, 2. buffets and restaurants, 3. grocery shops, 4. kebab shops, 5. cafés, 6. protein [poultry] shops and supermarkets, 7. ice cream parlors, fruit juice and soft drinks shops, 8. pastry shops, 9. coffee shops).[60]

Other government letters show that local authorities in different provinces were instructed to prevent Baha’is from occupying high earning jobs or to have businesses close to each other, for fear that they would become key decision-makers in trade or business.[61]

A Baha’i woman told Human Rights Watch that the license for her salon business in the city of Qazvin was not renewed after she was told by the head of the local trade union that Baha’is are not allowed to work in businesses that interact with water. The police responsible for public facilities and locations subsequently closed her shop.[62]

In recent years, local police forces have shuttered hundreds of small businesses across the country after the owners closed their shops during Baha’i holidays.[63]

In November 2016, authorities shuttered at least 94 Baha’i-owned local businesses after they had closed their businesses to observe Baha’i holidays on November 1 and 2 in Mazandaran province, HRANA reported.[64] According to the minutes of a meeting of the “religions and sects office” at the Mazandaran province governor’s office on October 30, 2016, authorities decided to close local Baha’i businesses in the province.[65] According to the meeting minutes, “divine religions have rights according to the constitution of our beloved country, …but the Baha'i sect has no originality and has English and Zionist roots, and in order to divert the thoughts of the masses they engage in coordinated activities, most importantly organizational and psychological work in the issue of human rights.”[66]

On June 10, 2017, Branch 5 of the Court of Administrative Justice ruled in favor of the Baha’i business owners, ordering the reopening of the businesses and referring to article 28 of trade union law, which states that only small business closures of more than 15 days can be penalized by authorities.[67] Despite the court order, as of February 2020, several of the businesses had yet been permitted to reopen[68]

HRANA has tracked the number of reported cases of authorities ordering the closure of Baha’i owned businesses in recent years as follows:

|

Year |

March 2022-March 2021 |

March 2021- March 2020 |

2020-2021 |

2019-2020 |

2018-2019 |

|

Number of cases |

9 |

8 (1 case has been closed for more than one year) |

57 (46 cases have been closed for between 3 to 8 years) |

33 |

354 (96 cases have been closed for more than a year) |

Land Grabs, Confiscation, and Demolition of Baha’is’ Property

Over the past four decades, Iranian authorities have used various laws and policies to confiscate at least hundreds of properties belonging to Baha’is. In 2006, the UN Special Rapporteur on adequate housing reported that Iranian authorities had confiscated approximately 640 properties belonging to Baha’is since 1980.[69]

More recently, authorities have used article 49 of the constitution, the primary legal basis for confiscating lands from citizens, to take over the ownership of Baha’i lands, business premises, and residences. The article allows the state to take ownership over wealth accumulated through activities such as “usury, usurpation, bribery, embezzlement, theft, gambling… [and] establishment of places of corruption and other illicit matters.”[70] This originated from Ayatollah Khomeini’s 1979 order to immediately “confiscate properties and wealth belonging to the Pahlavi dynasty, its branches, agents and relevant (persons or entities) in favor of the poor,”[71] and a 1984 law that was passed to implement this constitutional article.[72]

In 1989, Ayatollah Khomeini appointed three representatives to oversee the implementation of the order, effectively establishing what is now known as the headquarters for the “Execution of Imam Khomeini's Order (EIKO),” also known as Setad. [73] In 2001, Ayatollah Hashemi Shahroudi, then-head of the judiciary, communicated additional guidelines for implementation of article 49, designating specific branches of the revolutionary courts with jurisdiction over these cases.[74] Today, EIKO, under the supervision of the supreme leader’s office, is a state-owned business enterprise with significant shares in major economic assets in the country.[75]

Over the past few years, BIC and human rights lawyers inside Iran have reported on several cases of land confiscation and disputes, particularly in rural areas, involving members of the Baha’i community. They have repeatedly warned about the increasing trend of EIKO confiscating Baha’i-owned properties.[76]

Case of Eyval Village in Mazandaran Province

On November 4, 2019, the Special Court for Article 49 of the Constitution, Mazandaran Branch, ruled that EIKO could confiscate land belonging to Baha’i families in the village of Eyval, “so that by the sale of the land to people with meager properties in the village of Eyval, a cultural center may be established for the propagation of the hidden Imam and the remaining funds from the sale of these lands could be used for cultural matters and the expansion, development and flourishing of the village.”

These properties, approximately 50 houses, originally belonged to Baha’i families, but they were set on fire and demolished in 2010.[77] Baha’i families had warned local authorities about the possibility of attacks on their houses, but their pleas for help were reportedly ignored. Baha’i families proceeded to file complaints within the judicial system after the attack, but no one was held accountable for damage to their property.[78]

According to BIC, at the time of the 2019 order, the majority of these houses were vacant, as the families had been driven out of the village in previous decades.[79]

In the order deciding EIKO could confiscate the Baha’i properties, the Special Court for Article 49 of the Constitution explained the basis for its ruling as follows:

“The perverse sect of Baha’ism is confirmed as heretical and unclean (nijasat); there is no legitimacy in their ownership, and it is incumbent upon the fervent believers to confront the deception and corruption of this perverse sect and prevent the deviation and attraction of others towards them, and any contact with them has been declared haram… and given that certain individuals associated with this perverse faith among their leaders are now outside the country collaborating with the opposition groups against the regime, the court rules that there is no legal merit in leaving the remaining properties in the possession of the perverse sect of Baha’ism in the Village of Eyval, Chahar Dangeh Division, and issues a court order in that effect.”[80]

On October 13, 2020, the court of appeal in Mazandaran upheld the confiscation.[81] According to the lawyer who represented the Baha’i families whose property was seized, their latest attempt to appeal was rejected on October 21, 2021.[82]

Case of Irrigated Lands in Kata Village in Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province

On December 5, 2021, in a public statement, BIC warned about an advertisement posted by EIKO on an auction website the previous October. The advertisement referred to an auction of 13 parcels of land. This land had been confiscated from Baha’i families years before.[83] BIC estimated that each property was listed for sale at a price at only about 15 percent of its fair market value. The original Baha’i property owners were excluded from participating in the auction to buy back their own properties.

On October 11, 2000, in a letter issued by the head of EIKO in Fars province to the head of the judiciary in Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad province, the head of EIKO asked the judiciary to facilitate the confiscation and transfer of these properties, which, at the time, were still in the possession of Baha’is. The EIKO head cited a court order dated April 18, 1994 ordering the transfer of the properties.[84] Four court documents issued in 2002, 2007, 2008 and 2016 show that the lands were eventually confiscated, based on article 49 of the constitution, after the owners, who belonged to the Baha’i faith, had, according to the documents, “fled” the village.[85] In a verdict issued by the Special Court for Article 49 of the Constitution of Mazandaran, which was reviewed by Human Rights Watch, the court cites the original property owners’ activities promoting the Baha’i religion inside and outside Iran as a basis to rule in favor of the EIKO seizure of the their property.[86]

Baha’is in Semnan

On August 22, 2022, Saeed Dehghan, a lawyer, tweeted that Branch 1 of the Semnan Revolutionary Court ordered the confiscation of several Baha’i properties in the province, with transfer to EIKO. According to the court, authorities had discovered incriminating evidence “at the home of Mr. Jamaloddin Khanjani, an official of the illegal Baha’i organization.” Khanjani was one of seven members of the former Yaran, a local, ad-hoc administrative group for Baha’is, who spent 10 years in prison. According to Dehghan, the authorities found a single sheet of paper with a few addresses and the names of individuals and businesses in Khanjani’s house which they used as the basis for confiscating the properties.

Branch 54 of the Tehran Revolutionary Appeals Court, under the supervision of Hassan Babaei and Behzad Ebrahimi, upheld the ruling of Semnan Revolutionary Courts. According to documents reviewed by Human Rights Watch, the revolutionary courts in Semnan determined that despite having private owners, the properties on the list could be confiscated under constitutional article 49 because they were properties belonging to “those who were members or active in freemasonry establishment or in contact with international spying agencies.”[87]

Baha’is in Roshankouh

On August 2, 2022, HRANA and the BIC reported on the confiscation of 20 hectares of farmlands and the demolition of six homes in the village of Roshankouh in Mazandaran Province.[88] Authorities claimed that the Baha’is had encroached on lands designated as a nature reserve, despite the Baha’is being in possession of property deeds to the lands that some families had farmed for over a century. The authorities left the houses of adjacent neighbors intact while demolishing only the homes of the Baha’is.

Restrictions on Civil Rights and Dignified Burial

Baha’is face significant discrimination in matters of personal status and legal recognition. During the presidencies of Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami, covering the period from 1989 to 2005, Iranian authorities gradually granted Baha’is a few basic civil rights, such as the right to register marriages and to obtain passports. But Baha’is still face many hurdles and discrimination in matters of personal status and civil rights.

Iranian courts have refused to grant inheritance to Baha’is. Two court documents issued on June 2, 2000, and July 4, 2007, show the courts refusing to issue inheritance decrees to Baha’is because they are not recognized as a religious minority.[89] The 2007 verdict rejected the inheritance request on the grounds that “issuance of an inheritance decree to Baha’i individuals would be considered a form of recognizing Baha’ism, which is against constitutional law, established laws, and the common order.”[90]

Baha’is have also struggled to obtain basic identification documents. In 2020, the new application form for receiving a national ID card, a document essential for conducting basic activities in Iran, briefly excluded Baha’is. The form required applicants for the card to choose from one of the recognized religions. However, the requirement has reportedly not been fully implemented.[91]

In 2023 the authorities introduced a new digital registry system for the registration of marriages, which has now denied the Baha’is the right to register their marriages. The online system requires couples to state their religious affiliation, which only provides options for the four recognized religions and does not provide an option to select “Baha’i” or “Other”. The result of this action is that Baha’is are now excluded from registering their marriages, which also effects the registration of births, divorces, and inheritance.

According to Amnesty International, after the 1979 revolution, Iranian authorities desecrated and, in some cases, demolished Baha’i cemeteries across the country.[92] To date, Baha’is report that local authorities interfere with burial processes and refuse to allow Baha’is to bury their loved ones in historically Baha’i cemeteries. In one of the latest cases, the BIC spokesperson said that in April 2021, authorities attempted to prevent Baha’is in Tehran from burying their deceased in a place previously allocated to them in Tehran’s Khavaran cemetery.[93] Authorities reportedly temporarily reversed their decision under national and international pressure, but in recent months have again increased pressure on the Baha’i community to bury their loved ones elsewhere—in an area which is believed to be the site of a mass grave of thousands of individuals killed in a mass execution of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience in the summer of 1988. On April 29, 2023, Radio Farda reported that authorities buried at least three Baha’is in that area without the consent of the family or a proper religious burial process.[94] BIC has reported that this number has subsequently risen to scores of forced burials in the Khavaran mass grave site as at the end of November 2023.[95]

III. Impact of Legal Religious Discrimination on Baha’is

Discrimination Codified in Iran’s Constitution

After the revolution, Iran’s constitution designated Islam as the official religion of the country and Shi’ism as the official Islamic sect. The constitution granted some other schools of Islam close to full protection of the law and recognized certain, specific religious minorities. [96] According to article 13 of the constitution, “Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian Iranians are the only recognized religious minorities, who, within the limits of the law, are free to perform their religious rites and ceremonies, and to act according to their own canon in matters of personal affairs and religious education [emphasis added].”

Religious minorities that are unrecognized in the constitution, including Baha’is, are not entitled to such limited constitutional protection, and face greater discrimination in criminal and civil law.

Baha’is, like other unrecognized religious minorities, are prevented from having any official religious institutions in the country, unable to freely hold prayers, and prohibited from performing other acts as part of their religious practice.[97] While most elected and non-elected positions in Iran’s political system are solely open to Muslims, there are some limited positions (e.g., members of parliament) allotted for recognized religious minorities within a quota system. Members of unrecognized religious minorities, including the Baha’is, are banned from holding any government or public sector position.

Discrimination Rooted in Iran’s Legal Codes

Iran enshrines discrimination against religious minorities throughout its legal system. For example, penalties in criminal law for members of religious minorities (both recognized and unrecognized) differ from those enjoyed by the Muslim majority for certain crimes. Iran’s penal code states that non-Muslims will be subjected to more severe penalties than Muslims for the crimes of adultery, homosexuality, and premeditated murder. For adultery and tafkhiz (putting a male sex organ between the thighs or buttocks of another man), a non-Muslim male will be punished by the death penalty, according to Iran’s penal code, while a Muslim male will be punished by floggings.[98]

Further, non-Muslims in Iran, including Baha’is, are unable to access certain remedies when they or their family members have been the victim of a crime.[99]

Members of the Baha'i community also face discrimination in matters related to personal status. In March 2022, the UN special rapporteur on freedom of religion said in a report that being a member of the Baha’i faith can result in “the loss of custody of children in divorce proceedings the non-recognition of marriages, and the state disregarding contents of wills or Baha'i inheritance laws in disputed estate matters.”[100] According to government documents published by BIC, following numerous complaints made to the administration of President Mohammad Khatami, on February 21, 2000, then-deputy interior minister and executive political director of the interior ministry communicated to governors’ offices that registering “marriages of couples without listing their religion, whether they are from non-Islamic sects or unofficial religions, is now allowed.”[101] Two interviewees explained, however, that Baha’i marriages are registered by recording the affidavits of the two spouses (as opposed to registration by the state).

IV. Legal Analysis

Human Rights and Minority Rights’ Protections

As a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Iran is obligated to protect everyone’s right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. Under ICCPR’s article 18:

This right shall include freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice, and freedom, either individually or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching.[102]

The Human Rights Committee’s general comment on ICCPR’s article 18, states that:

The concept of worship extends to ritual and ceremonial acts giving direct expression to belief, as well as various practices integral to such acts, including the building of places of worship, the use of ritual formulae and objects, the display of symbols, and the observance of holidays and days of rest. …In addition, the practice and teaching of religion or belief includes acts integral to the conduct by religious groups of their basic affairs, such as the freedom to choose their religious leaders, priests and teachers, the freedom to establish seminaries or religious schools and the freedom to prepare and distribute religious texts or publications.[103]

Under international law, states are obliged to not only protect ethnic, cultural, and religious minorities, but also to protect their identities, to ensure there is no discrimination against them in their enjoyment of their rights and to ensure their meaningful participation in the public affairs.[104]

Among other documents, these obligations are spelled out in the non-discrimination clauses of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). Article 27 of ICCPR states that:

In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their own religion, or to use their own language.[105]

These rights are further elaborated in the 1992 UN Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities.[106]

Iran is a party to both the ICCPR and ICESCR. It is clear, however, not only that the Iranian authorities have failed to fulfil their obligations to protect the rights of Baha’is, including their rights to freedom of religion, education, work, freedom from arbitrary arrests, fair trials enshrined in the covenants, but they have gone even further by launching a relentless campaign, led by the highest levels of government, to “contain” and “block the progress” of Baha’is as a religious minority.

It is important that states and the United Nations institutions press the Iranian authorities to halt the violations against and protect the rights of the Baha’is and other religious minorities. But the cumulative impact of ongoing violations against the Baha’i community amounts to severe violations of fundamental rights and may amount to an international crime.

Crime Against Humanity of Persecution

The 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which came into force in 2002, sets out 11 crimes that can amount to a crime against humanity when “committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack.”[107]

“Widespread” refers to the scale of the acts or number of victims. A “systematic” attack indicates a pattern or methodical plan. Crimes against humanity can be committed during peace time as well as during armed conflict, so long as they are directed against a civilian population. The Rome Statute defines “attack” to mean that the crime needs to be committed as part of a policy of the state or of an organized group.[108]

The policy requirement, along with the need for such crimes to be widespread or systematic, limits crimes against humanity to the “most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole.”[109] All states have an obligation to ensure that crimes against humanity are punished and that those responsible are held accountable.

Among the 11 categories the Rome Statute defined as crimes against humanity is the crime of persecution.

The crime against humanity of persecution can originally be found in the Charter of the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal in 1945, which defined crimes against humanity as including “persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds.”[110]

The Rome Statute defines persecution as the intentional and severe deprivation of fundamental rights contrary to international law by reason of “the identity of the group or collectivity,” including on national, religious, or ethnic grounds.[111]

The Statute limits the crime to applying only “in connection with” other crimes identified under it.[112] The customary international law definition of persecution, though, includes no such limitation.[113]

International criminal lawyer Antonio Cassese, who served as a judge in the leading ICTY case that examined persecution within international criminal law (Prosecutor v. Kupreskic), identified the crime against humanity of persecution as a crime under customary international law.[114] He defined persecution under customary international law as referring to acts that (a) result in egregious or grave violations of fundamental human rights, (b) are part of a widespread or systematic practice, and (c) are committed with discriminatory intent.[115]

Liability for serious crimes under international law is not limited to those who carry out the acts, but also those who order, assist, or are otherwise complicit in the crimes. That includes liability on the basis of command responsibility in which military and civilian officials, up to the top of the chain of command, can be held criminally responsible for crimes committed by their subordinates, when they knew or should have known that such crimes were being committed, but failed to take reasonable measures to prevent or stop them.

Iranian authorities regularly claim that Baha’is are targeted for committing national security crimes, but an abundance of judicial and policy documents make it clear that Baha’is are targeted because of their identity as a religious group. In fact, in numerous instances Iranian authorities have told Baha’is who were excluded from university or arrested and sentenced that to avoid these punishments they need to simply identify as Muslim in order to have their rights restored. This attitude is also reflected in official educational, employment, and civil documents and forms where applicants are only given the option of choosing from a recognized religion and Baha’is are encouraged by local official to simply choose the category Muslim to “avoid trouble.”

The existence of numerous policy documents and regular references in judicial proceedings demonstrate that these egregious rights violations are committed as widespread state policy that is directed at the highest level. The cumulative impact of discriminatory and depredatory policies amount to serious violations of Baha’is’ fundamental rights including freedom from arbitrary arrest and persecution, as well as economic rights such as to education and work. These measures appear to be taken with the intent to economically strangulate the community (for example, from the 1991 memo).

Systemic violations spelled out in this report including Baha’is rights to freedom of religion, education, work, freedom from arbitrary arrests, fair trials as well as authorities’ overarching policy to prevent Baha’i’s progress as a community are widespread and ongoing to this date.

Human Rights Watch believes that because of the gravity of these ongoing violations and that they are conducted in a systematic manner and with a clear discriminatory intent, they amount to the crime of persecution and that this should be investigated by credible judicial authorities. This would be the standalone crime of persecution under customary international law. It could also amount to the crime against humanity of persecution under the Rome Statute, in connection with other crimes under that Statute including the crimes of enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention, murder or other inhumane acts.

Criminal accountability is not only a crucial element of justice for those affected by the abuses but also an essential part of preventing the commission of such crimes in the future.

Iran is not a party to the International Criminal Court (ICC). Iran has also not incorporated crimes against humanity into its domestic legal framework. But under the principle of universal jurisdiction national judicial authorities in other countries can pursue cases involving serious crimes. "Universal jurisdiction" refers to the authority of national judicial systems to investigate and prosecute certain of the most serious crimes under international law no matter where they were committed, and regardless of the nationality of the suspects or their victims.

Countries have not uniformly implemented international law and universal jurisdiction into their national laws. As a result, some countries have universal jurisdiction for some crimes and not for others, and the starting date for such jurisdiction can vary. Most countries’ laws require the suspect to be present on their territory.

Over the past two decades, the national courts of an increasing number of countries have pursued cases involving grave international crimes such as war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearance, and torture committed abroad. These experiences show that fair and effective exercise of universal jurisdiction is achievable where there are the right judicial commitments, adequate resources, and a combination of appropriate laws and political will.

On July 14, 2022, a court in Stockholm, Sweden sentenced a former Iranian assistant prosecutor to life in prison on charges of “grave war crimes and murder,” for his role in the mass executions of political prisoners in 1988 in Iran. The trial marked the first time an Iranian official accused of participating in 1988 mass executions appeared before a judicial body, giving a unique opportunity for survivors to testify in a court of law. Over nine months, dozens of survivors previously imprisoned due to membership in banned organizations testified about their detention conditions, torture they suffered, and summary executions of prisoners they witnessed.[116]

Rights of Baha’is to Remedy and Reparation

Apart from investigating the commission of international crimes and holding those accountable for serious violations against Baha’is for more than 40 years, and in cases that do not rise to the level of criminal accountability, Iranian authorities are obligated to provide victims of gross human rights violations with compensation. In according the Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law the victims should be provided with full and effective reparation, which include restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and guarantees of non-repetition. According to the basic principles “compensation should be provided for any economically assessable damage, as appropriate and proportional to the gravity of the violation and the circumstances of each case, resulting from gross violations of international human rights law and serious violations of international humanitarian law that includes:

(a) Physical or mental harm;

(b) Lost opportunities, including employment, education and social benefits;

(c) Material damages and loss of earnings, including loss of earning potential;

(d) Moral damage.[117]

Acknowledgments