NEW YORK- If you listened to the talking heads on U.S. television, you would think that the United States has only two choices for prosecuting accused Qaida terrorists: either summary trials under President George W. Bush's order for military commissions that would allow the government to convict and execute suspects with no presumption of innocence, no need to prove guilt beyond reasonable doubt and no right to appeal; or O.J. Simpson-style legal circuses with cameras in the courtroom, huge pressure on frightened jurors and evidence being thrown out because the Special Forces didn't read the suspects their Miranda rights.

The federal courts remain the best option for trying terrorist suspects apprehended in the United States - and they have an excellent track record in doing so. But there is another option theoretically permitted by the president's order, that meets all the administration's stated needs of security and flexibility but which would guarantee fair trials: Try suspected terrorists captured in combat in military commissions that use the protections contained in the Uniform Code of Military Justice. These are the same due process protections already used for military courts-martial.

The Department of Defense is now drafting the guidelines for implementing Mr. Bush's order. Whether the administration seizes this chance to preserve the option of military trials while assuaging their critics depends on whether it understands the high stakes for the United States in getting this decision right.

That foreign terrorist suspects captured in Afghanistan do not enjoy the same constitutional rights as Americans is almost beside the point. There are other principles of fairness involved - principles central to America's self-image as a just society, principles critical to ensuring the legitimacy of any judgments rendered by a military court and principles enshrined in international law that the United States has rightly preached overseas.

Just this year, for example, the State Department's annual report on human rights practices around the world concluded that military courts in Egypt, which have been used to try not only those accused of violence but peaceful dissidents, have "deprived hundreds of civilian defendants of their constitutional right to be tried by a civilian judge."

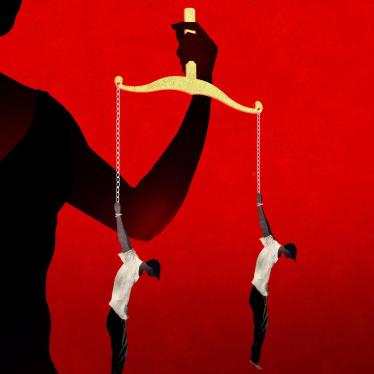

If not narrowed by appropriate guidelines, Mr. Bush's order will permit trials exactly like those America has condemned abroad. Tomorrow's military dictators will need to do nothing more than photocopy the Bush order to secure a repressive mechanism that will ward off future U.S. criticism.

The irony is that for decades, the American system of military justice has been a model of a different kind - a model of fairness and respect for individual rights that was written, by definition, for times of war as well as for times of peace. Here is what the administration can do to stay true to American traditions:

First, commissions should be used to try only persons engaged in armed conflict against the United States for violations of the laws of war. All defendants should be able to file a habeas corpus petition to challenge the lawfulness of their detention and, as the Uniform Code of Military Justice provides, no one should be indefinitely detained without trial.

Second, trials by military commissions should be public, consistent with the basic requirements of protecting classified information. As the military's rules for courts-martial state, public trials "reduce the chance of arbitrary or capricious decisions and enhance public confidence."

Third, military commissions should apply the due process protections used in courts-martial - including the right of defendants to have counsel of their choice, to cross-examine witnesses and to be presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond reasonable doubt. If the death penalty is applied - a decision that should be re-examined in light of the growing worldwide condemnation of this practice - it should not be imposed except by unanimous vote, as the Uniform Code of Military Justice requires. And all defendants should have the right to appeal to an independent judicial body, such as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces.

In effect the administration has one critical choice: It can let Mr. Bush's order stand as it is, and let it become a virtual code of misconduct for authoritarian governments around the world. Or it can show what the U.S. system of military justice was meant to show: that America does not abandon its commitment to human rights in times of conflict, but affirms it as an enduring source of national strength.